By Navin Bapat

The Washington Post’s publication of the Afghanistan Papers reveals that, although the official line was that the war was turning in favor of the US and its allies in Kabul, policymakers have long been aware that the situation was bleak, deteriorating, and unlikely to produce anything resembling a “victory.” Following 9/11, the US identified failed states as a key national security risk, in that these environments enabled terrorists, rebels, warlords, and other non-state actors to plot and plan operations against the US and the international community. Given that Afghanistan seemed to represent the prototypical weak state, the solution was obvious: Afghanistan needed to be transformed into a strong state that would resist non-state actors—particularly terrorist groups such as Al Qaeda. But in trying to achieve this lofty goal, the US has lost thousands of soldiers and contractors and spent several trillion dollars—and the costs will likely continue rising. The Afghans themselves have suffered even more, with over 100,000 deaths since 9/11. Despite all of this loss—and the open acknowledgment that the strategy is failing—there is little appetite among US policymakers for reversing course.

Why is this the case? The Afghanistan Papers provide several explanations for why the US effort is failing. The interviews demonstrate that a capable strategy never existed, the training of the Afghan military was slow and only accelerated as the Taliban threat worsened, corruption was rampant, and drugs became a significant part of the Afghan economy. And tying each of these issues together is one central, devastating observation: Operation Enduring Freedom increased the profitability of war.

Most arguments in the literature assume that war is costly, and for good reason. However, most political policies are assumed to produce winners and losers, and leaders may survive in power despite making seemingly ruinous choices. In this case, while the war brought loss to thousands of Afghans, the US security guarantee insulated the Afghan government from the costs of war and allowed its members to reap substantial and lucrative benefits. Those benefits, in turn, reduced their incentives to stop the conflict.

As the Afghanistan Papers show, though the principals had differing objectives in mind with regard to Afghanistan, the one thing everyone agreed on was that the US needed to prevent the Taliban from returning to power, which could, in theory, allow Al Qaeda to resurface in the territory. The Afghan government was meant to serve as a vehicle to accomplish these objectives. The US would build a strong central government led by one of its former CIA assets: Hamid Karzai. Karzai effectively, therefore, had one job: fight the Taliban and stop them from achieving victory. But stopping the Taliban from achieving victory did not necessarily mean defeating them outright. After eight years of fighting, over 1,000 fatalities, and $100 billion dollars spent, Ambassador Karl Eikenberry concluded in 2009, that: “Karzai continues to shun responsibility for any sovereign burden, whether defense, governance, or development. He and much of his circle do not want the U.S. to leave and are only too happy to see us invest further.” That same year, Karzai declared that Afghanistan would continue to need US help for 15-20 years.

In my book Monsters to Destroy: Understanding the War on Terror, I examine the logic and predicted consequences of the US strategy to provide hosts of terrorist groups with economic and military aid. I argue that if the US was willing to pay Karzai’s government to fight terrorists, the Afghans would have incentives to fight terrorists forever. Since fighting terrorists guaranteed that the US would shower the Afghan government with support, and American support would likely terminate once the threat of terrorism was over, few actors in the Afghan government had any incentive to stop the conflict. The US was subsidizing the Afghan government, which was happy to allow the US to pay the price of the war in its own blood and treasure. With guaranteed American support, members of the Afghan government could engage in graft, theft, extortion, drug trafficking, and racketeering, all with the comfort of knowing that no matter what they did, the Americans would protect them—because, politically, America cannot lose wars, especially to a group associated with the 9/11 attacks. In this sense, the security guarantees provided to Afghanistan by the US prevented the government from absorbing the costs of war and allowed its members to reap substantial and lucrative benefits.

The evidence of this problem is clear. The Afghanistan Papers detail that, despite enormous resources spent on Afghan security, there is little to show for the effort: Afghanistan’s government and military remain weak and brittle. Further, the papers reveal that some Afghans have little intention of ever using American resources to suppress the Taliban insurgency. And since growers of opium poppy recognized that the US was not interested in harming the Afghan economy, they would declare their willingness to burn their crops in exchange for cash. After receiving the payments, the growers would subsequently sell their opium. If the US was going to continue supplying them with capital so long as they professed anti-Taliban sentiments, Afghan growers could double their profits.

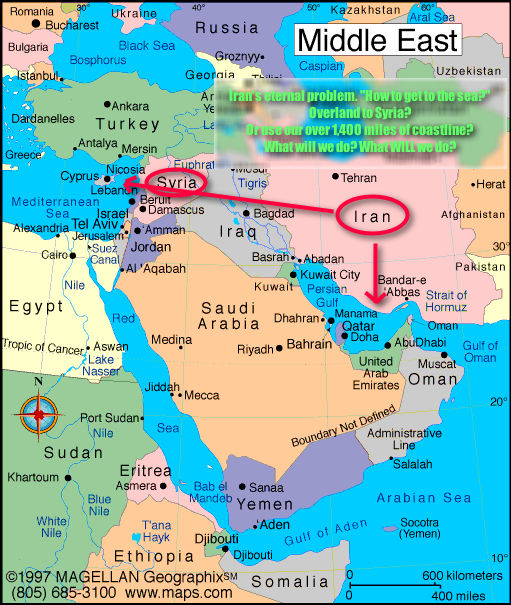

Sadly, the Afghan experience is one in a considerable number of similar cases in the war on terror. Since the US strategy was to protect governments facing terrorist threats, and arm them so they could fight terrorists, why would any of these governments say no? If they cooperated, they gained indefinite protection. However, because they had indefinite protection, each of these states had incentives to engage in abuses with impunity. Pakistan and Yemen echo the failures of Afghanistan, where both Pervez Musharraf and Ali Abdullah Saleh seemed happy to receive American support to fight terrorists in perpetuity while taking less-than-decisive action against these groups. In each of these cases, the business of fighting terror proved incredibly lucrative, and there was simply no reason to slay the cash cow.

While wars are costly, like any policy, war produces winners and losers. In this case, the war on terror has caused incredible destruction in states that have participated in it. Hundreds of thousands of Afghans, Pakistanis, Yemenis, and Iraqis have been killed in the process—not to mention significant casualties in other theaters. Further, thousands of Americans have lost their lives, and tens of thousands have been wounded by the war. The US spent trillions of dollars, devoting resources away from investments in education and infrastructure, and increased its liabilities for future veterans’ health care costs and interest payments on its debt. Given these terrible costs, the US is attempting to secure peace by negotiating directly with the Taliban. However, such an action will almost certainly meet a political backlash and will cede the US position in Central Asia to Russia and China, two of its geostrategic rivals. Further, the Afghanistan Papers indicate that the “winners” from the war effort in the Afghan government may not quietly allow peace to take away what they have gained from violence.