Guest post by Austin C. Doctor and Stephen Bagwell

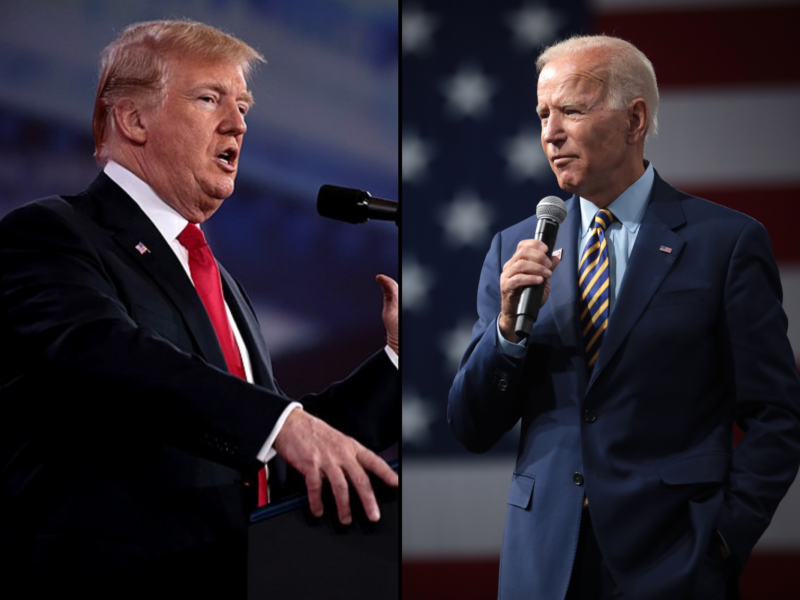

Concern is growing that the coming US election season will be marked by intensified violence, heightened by President Trump’s recent call for the Proud Boys to “stand down and stand by.” Increasingly, red flags used to identify likely outbreaks of election-related violence in other countries are emerging in the United States. Are US democratic institutions strong enough to withhold the pressures they now face?

Acts of electoral violence attempt to manipulate the outcomes of an election cycle through physical violence and coercive intimidation. Common forms of electoral violence include the threat or use of force against opposition leaders and supporters, targeted violence against key voter bases, clashes between supporters of rival parties, and attacks on visible manifestations of elections.

Warning signs of electoral violence in the United States

Academic research on electoral violence identifies several factors that increase the risk that actors with a stake in an election will choose to employ violent tactics. Some of them are taking root in the ongoing American presidential election cycle.

The stakes in this election are high

When the stakes are high, political partisans are more motivated to manipulate electoral outcomes in their favor, even violently. For the two American political parties—and their supporters—there is much to be won or lost in this contentious election. Biden frames his campaign as a “fight to restore the soul of America.” Trump claims this to be “the most important election in US history.” This dynamic is exacerbated by the US “winner-take-all” electoral system, which raises the stakes of the election, and by the growing polarization between the country’s partisan camps, which reduces opportunities for cooperation and compromise. As a result, in the eyes of many, the winner of the current executive election will possess an ability to privilege one side of the growing divide.

The incumbent is running—this incumbent, in particular

Elections are more likely to turn violent when an incumbent is running and faces uncertainty at the polls. With national forecasts consistently showing Biden in the lead, President Trump is laying the groundwork to challenge the fairness of this election by, for instance, casting doubt on the trustworthiness of mail-in ballots. Should the president lose in November, it is likely that Trump will call fraud. This despite the fact that multiple investigations have found no credible evidence of widespread voter fraud to date—save from that of the president’s own party.

Accusations of fraud may be used to justify later violence or repression by state security forces (such as federal Border Patrol officers), or pro-Trump armed groups. An August 2020 report produced by the bipartisan Transition Integrity Project concluded, “The potential for violent conflict is high, particularly since Trump encourages his supporters to take up arms.”

The steady rise in militant activity

Finally, electoral violence may extend from an emerging feature of American politics: the militarization of protest, counter-protest, and repression. In short: the latent opportunity for electoral violence in the United States may increase as other forms of “armed politics” become more commonplace.

Federal security forces and police units in the United States continue to militarize, both in their culture and hardware. Despite bipartisan efforts to curb the practice, in 2017, President Trump reversed restrictions on the flow of surplus military equipment from the Pentagon to federal and local law enforcement departments. This year, the Trump administration has used these agents to counter local protests in Portland and elsewhere. Should contention over the outcome break out, similar tactics are likely to be employed.

In other countries, electoral violence is most commonly carried out by pro-government forces—state security forces or loosely organized non-state armed groups such as militia or vigilantes. Latter cases might be classified as evidence of an “overt indirect” strategy employed by armed groups to support the re-election of the incumbent. In Trump, many in the far-right believe they have an ally. As recently reported in The Atlantic, when Trump warned of election fraud in the 2016 election, the leader of Oath Keepers called on group members to quietly monitor polling stations. Trump has recently encouraged such practices.

Mitigating features of electoral violence in the United States

Despite the factors highlighted above, the emergence of sustained or widespread electoral violence in November is certainly not inevitable. There are a number of risk-reducing features in place.

Strong political institutions

First, strong political institutions place effective restraints on surges in political violence, and consolidated liberal democracies like the US are far less prone to electoral violence than illiberal regimes. Despite its relative political instability of late, the United States is neither Kenya circa 2007/2008 nor Côte d’Ivoire circa 2010. The US is one of the oldest democracies in the world; cases of voter fraud are rare; and in the case of a disputed election outcome, the authority to decide a winner of the presidential election in the US is vested in separate branches of government, including the Supreme Court. Moreover, where a strong rule of law ensures that civilian violence is punished, would-be perpetrators of violence, as well as the inciting politicians, risk incurring significant costs. As a result, institutionally speaking, the United States is indicative of a case that typically shows lower risk of sustained electoral violence.

Denouncement of military engagement

Second, the formal denouncement of electoral engagement by the military offers further legitimacy to the presidential election, reducing the threat of escalating violence between state and non-state forces. “The Constitution and laws of the US and the states establish procedures for carrying out elections, and for resolving disputes over the outcome of elections… I do not see the US military as part of this process,” Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley stated in a recent letter to members of the House Armed Services Committee. This offers hopeful evidence that the United States’ military at large is committed to avoiding escalatory or controversial actions, which would feed the tensions building around the November election.

What’s Next?

Predicting the onset of political violence is difficult. Though existing research suggests some risk of violence around the upcoming presidential election—especially if Democratic candidate Joe Biden wins by a narrow margin—sustained or widespread electoral violence in November is not inevitable.

The next several weeks will see an embattled incumbent face a high-stakes electoral contest set in the backdrop of increased militancy in American politics. To limit any escalation of violence, leading members of both the Democratic and Republican parties should denounce and discourage the involvement of armed non-state groups, ensure the election process remains free, fair, and transparent, and commit to accepting the outcome in November.