By Katariina Mustasilta and Roman-Gabriel Olar

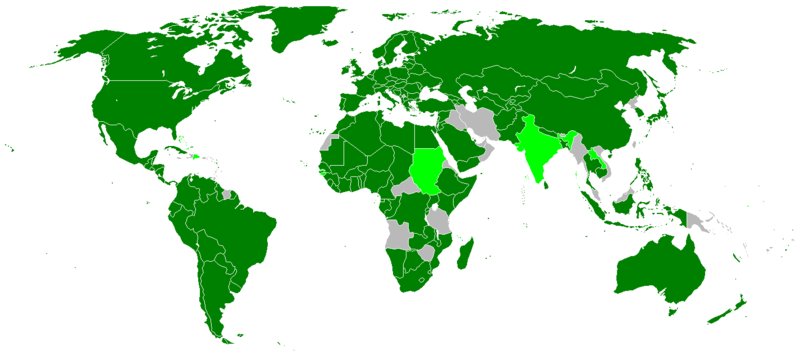

Countries around the world are increasingly relying on their militaries to battle the COVID-19 pandemic, with roles ranging from equipment distribution and establishing treatment and testing centers, to enforcing curfews and full community lockdowns. In Ecuador, the military has been put in charge of operational plans for the hard-hit Guayas region, while Senegalese military forces were ordered to be ready for “immediate and strict execution of the measures decreed throughout the national territory.”

These developments reflect an increasing trend of military involvement in public health management, a policy area traditionally reserved for civilians. Though there may be benefits to military involvement, research also suggests that there are dangers, including an increased likelihood of human rights violations, and opportunities for squashing political opponents and tightening the military’s grip on power.

Implications for Human Rights

While the organizational expertise and resources of the military can complement police and civilian resources, it can also have deleterious effects for human rights. Militaries are trained to protect countries from outside threats using force, and research suggests that the involvement of military personnel in policy areas reserved for civilians increases the use of disproportionate violence against civilians. One challenge that militaries have in these scenarios is distinguishing between the population that needs to be protected (the uninfected) and the victims who need to be isolated (the infected). The use of force may not be an adequate response to address this challenge. The killings of several residents of Monrovia’s West Point slum by military forces during the 2014 Ebola outbreak attests to this challenge.

The hierarchical and rigid command structure of the military puts additional strains on its ability to adapt its methods to enforcement of public order during public health crises. And the urgency of halting transmission of the virus incentivises governments to enact lax policy guidelines about the military’s role. Allowing members of the military to interpret policies and failing to develop mechanisms of civilian control by the state leads to sub-optimal and inefficient implementation of those policies.

Reports from Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya indicate disproportionate use of force in enforcing lockdown measures. The National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria confirmed on April 15, that extrajudicial killings of civilians outnumber deaths caused by COVID-19. Similarly, in Kenya the state has invoked powers under the Public Order Act that are informed by their experiences defending against the attempted coup of 1982 and the insurgency in the Mount Elgon region. Only now, instead of facing an armed insurgency, the opponent is a virus—an important difference missed by Kenyan officials. In South Africa, over 70,000 troops have been deployed to enforce the lockdown, most of whom are equipped with semi-automatic rifles. A dozen South African soldiers are already under investigation for allegedly killing a man in Alexandria township. In Rwanda, there have also been reports of sexual violence committed by military forces, and arbitrary arrests are widespread around the country.

Effects on Opposition Movements

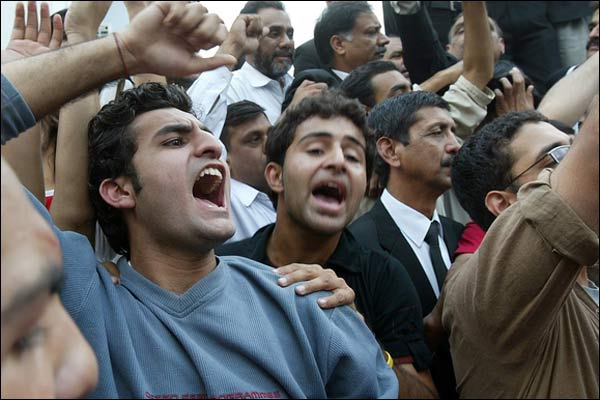

An unprecedented wave of nonviolent protests against autocracy was in full bloom before the pandemic, threatening to weaken entrenched autocrats’ grip on power. The COVID-19 crisis threatens to provide authoritarian-minded leaders the perfect cover to repress opposition members under the guise of protecting public health while reducing opportunities for peaceful assembly against the regime. Simultaneously, the elevated role of militaries may embolden opportunistic military leaders, who might use their strengthened status as a means to increase their material resources or even grab political power.

In India, amid the havoc caused by the pandemic, the Modi administration used its 2019 anti-terror law to crackdown on leaders protesting against the Muslim citizenship bill. In the Philippines, the Duterte government used claims of sedition and fake news to arrest members of the opposition who were critical towards the administration, most often unrelated to the pandemic. Similarly, the Hong Kong administration arrested over a dozen activists behind the 2019 protests in an attempt to curtail the activities of the pro-democracy movement. Activists expect this to be an initial step towards a larger planned crackdown against the opposition.

What about the effects of civil-military elite relations?

The pandemic may give military elites an advantage in bargaining over resources and consolidating their power. In Iran, the Revolutionary Guard—which was hit hard in the beginning of this year by the assassination of Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani—appears to be seizing the opportunity to strengthen its power vis-a-vis President Hassan Rouhani, by taking a commanding role in responses to the pandemic. This includes enforcing the quarantine law but also building treatment centers and screening patients, distributing aid, and disinfecting public spaces.

In Sudan, aside from reports of a power struggle between various factions of the military and the civilian leadership, there are also signs of the security forces expanding their operations to cover new functions and reinvent themselves. The infamous Rapid Support Forces is the most notable example. Aside enforcing the lockdown rules, they are using their time to disinfect the streets, run a quarantine center, and distribute medical equipment and advice. Civilian officials of the Sovereign Council have weakened ability to prevent or defend against potential military power grabs because they cannot mobilize their supporters in the street as they risk spreading the virus. Conversely, the inability of the civilian leadership to address the economic recession might leave it without allies to defend their democratic gains made after the ouster of Omar al-Bashir.

What exacerbates and what can mitigate these trends?

The world faces a long struggle against the pandemic, and some worrying conditions could increase the vulnerability of civilians, opposition movements, and civil rule. First, because the crisis consumes the public’s attention, human rights violations can be easily missed. This is exacerbated by the imposition of travel bans for human rights monitors and by the economic effects of the pandemic on the operational resources of human rights groups. Second, the length of the crisis, including second waves and the economic recession that follows, give more time and justification for emergency rules and codes to become the new normal.

Despite the dangers, societies can still push back against the erosion of democratic norms and the increasing role that militaries play in civilian policymaking. Firstly, nonviolent resistance has been found to be successful in bringing down dictatorships and protecting democratic gains. While the pandemic makes it harder for protesters to assemble, there are countless other tactics they can use to continue their struggle against oppression and authoritarianism. Indeed, activists have been quick to adapt to the challenges of protesting in an age of pandemic, and developed alternative means to indicate their displeasure with politicians and maintain the momentum of their dissent.

Political leaders aiming to curtail military opportunism can appeal to militaries penchant for organizational resources and reluctance to assume the outright governing of the country. Providing material resources to the military and ensuring their organizational independence can go a long way towards preventing military coups. National leaders can counterbalance the role of militaries by working closely with local leaders and governance structures, for example traditional leaders, in distributing information, aid and equipment during the crisis. Finally, international donors can support human rights groups and civil society movements in organizing civil society to push back against opportunistic attempts at grabbing power.

Roman-Gabriel Olar (@rgolar23) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Trinity College Dublin. He is also a Research Fellow at the Michael Nicholson Centre for Conflict and Cooperation, University of Essex. Katariina Mustasilta (@KMustasilta) is a Senior Associate Analyst at the European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS). The views expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.