Guest post by Danielle Gilbert

In late January, an American named Mark Frerichs was kidnapped in Afghanistan. Like Kevin King, Caitlan Coleman, and Bowe Bergdahl before him, he is believed to be held by the Haqqani Network, the Taliban’s notorious partners in high-stakes hostage-takings. As with prior cases of Americans kidnapped abroad, there have been reports of multiple lines of effort to bring attention to Mark’s captivity and secure his safe release, including family advocacy, a rescue mission, and rumors of high-level negotiations. Just this week, his sister penned a New York Times op-ed, urging President Trump to bring Frerichs home.

But there are two puzzling aspects of Frerichs’s kidnapping and captivity. First, it has received almost no media attention, despite coinciding with major US negotiations in Afghanistan. Given the ongoing Afghanistan peace process and reported Russian bounty payments to kill American troops, it is surprising that Frerichs’s case has been virtually absent from the news. Second, Frerichs was kidnapped a month before the United States signed a peace deal with the Taliban—and his release was not part of the deal. In other words, the Trump administration failed to use the leverage of the peace deal to ensure an American’s release from captivity.

In a recent article in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, I show how the media’s gatekeeping choices affect what foreign violence the public sees. Using an original dataset of more than 200 Americans kidnapped abroad between 2001 and 2015, and concomitant newspaper coverage of each victim, I identify the features of kidnappings that drive variation in coverage, to explain why some kidnappings become prominent national stories—and others barely make the local news.

Three crucial dynamics shape public perceptions of violence. First, framing violence as “terrorism” increases the coverage it receives. Second, incidents with fewer victims receive more coverage than those with many. And third, individual victim characteristics—from their race to why they were traveling—play a big role in which stories we see. Together, these dynamics help explain why you haven’t heard much about Mark Frerichs.

Framing matters

When the media describes a kidnapping as “terrorism” or refers to the perpetrators as “terrorists,” the incident receives far more coverage, regardless of whether the perpetrator is designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) by the US State Department. In fact, only one out of every three kidnappings committed by an FTO is described as “terrorism” by the media.

This may explain why there has been so little media coverage of Frerich’s kidnapping. Frerichs has only been the subject of two dozen stories, none of which frame the kidnapping as terrorism or the kidnappers as terrorists. Compare this to the 531 stories written about Bergdahl the year he was captured, 316 of which framed the abduction as terror. Given the apparent absence of guidance from the bully pulpit or consistency in framing across newspaper stories, calling a kidnapping “terrorism” appears to be the prerogative of individual journalists and media outlets.

One death is a tragedy; a million is statistics

As I have previously written for Political Violence @ A Glance, audiences pay more attention to single victims than they do to groups. According to the “collapse of compassion” hypothesis, variably expressed by Thomas Schelling and Josef Stalin, as the number of victims increases, audience sympathy for those victims ironically tends to decrease. Similarly, hostages kidnapped alone receive far more coverage than those kidnapped in groups; for every additional American hostage per incident, there are between 8 and 21 fewer stories about each victim.

Frerichs was kidnapped alone, so we might expect to see more stories about his captivity. However, data suggest that while a kidnapper’s first hostage receives substantial attention, subsequent hostages receive less. James Foley, the first American hostage beheaded by the Islamic State, was the subject of 1,375 newspaper stories. Steven Sotloff, the second American hostage killed, was the subject of 840; and Peter Kassig, killed later alongside a group of Syrian soldiers, was the subject of 216.

Who makes a “newsworthy” victim?

What other factors explain why some kidnappings receive so much attention and others are ignored? With origins in criminology and media studies, the “missing white woman syndrome” suggests that white, female, and especially young victims of abductions are far more likely to be reported than their male and non-white counterparts. Scholars have explored this phenomenon at length in North America, repeatedly demonstrating the disparities in coverage related to victims’ gender and race.

But neither race nor gender predicts coverage of kidnappings. However, within kidnapping incidents with multiple victims, the white victims receive significantly more media attention than their non-white counterparts. For example, Martin Burnham and Guillermo Sobero were kidnapped together and killed by Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines in 2001; Burnham, a white missionary, was the subject of 1,384 newspaper stories, while Latino businessman Sobero was the subject of only 495.

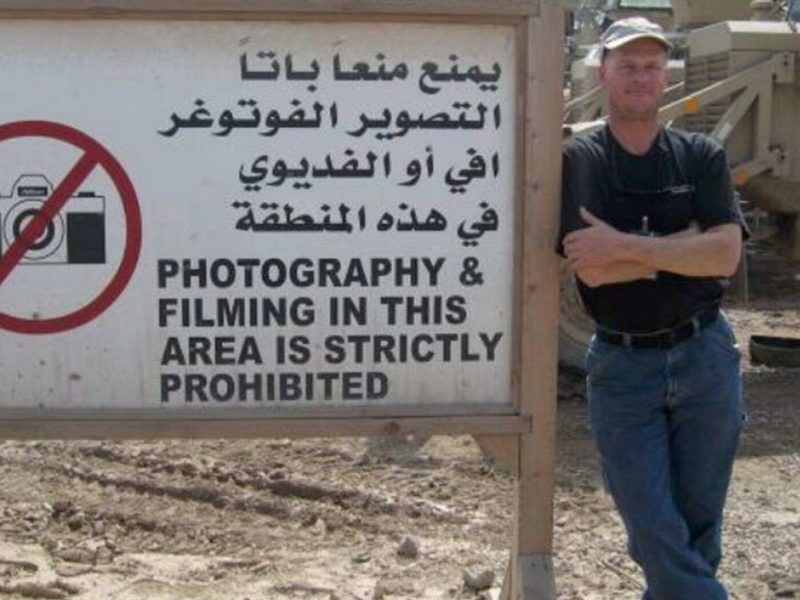

Underlying these disparities in coverage are biased perceptions about who counts as a “worthy” victim. For instance, hostages kidnapped while at work get more attention than kidnapped tourists. It may be easier to elicit sympathy for a victim who seems innocent or duty-bound than one whom the public may blame for walking into danger. In Frerichs’s case, early reports that he was abducted in Khost (rather than Kabul—where he was actually taken) may have erroneously suggested that he was courting danger.

As Eric Lebson, a former national security official who volunteers in support of hostage families, noted: “I have worked on several cases where the public narrative of an American hostage’s disappearance is inaccurately portrayed in the media, and it has an impact on how a case is covered.”

The oxygen of publicity

Political, psychological, and prejudicial biases play an enormous role in our understanding of international violence. Moreover, if, as scholars suggest, terrorists seek to maximize public attention for spectacle, the media’s role in framing and sharing hostage-taking violence might inadvertently support those goals.

Much remains unknown about the myriad decisions kidnappers make before a kidnapping ever makes the news—including why they sometimes choose to keep a kidnapping quiet, or why a family might refrain from a public pressure campaign. But, as I’ve written elsewhere, the cases generating the most public attention may be those most likely to get government help. Perhaps more attention to Mark Frerichs’ plight would ensure that when America departs Afghanistan, he is not left behind.

Danielle Gilbert is an Assistant Professor of Military & Strategic Studies at the United States Air Force Academy. The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not reflect the official position of the United States Air Force Academy, Department of the Air Force, or Department of Defense.