By John Gledhill, Allard Duursma, and Christopher Shay

Here’s a quiz question: What do Miley Cyrus, Lin-Manuel Miranda, REM, Jon Batiste, and Eurovision winner Ruslana have in common? If your answer is that they’ve all had chart-topping records, then you’re right. But if your answer is that they—like a host of other musicians over the years—have helped draw big crowds to protest rallies by performing at those events, then you get a bonus point. (There were clues in the hyperlinks.)

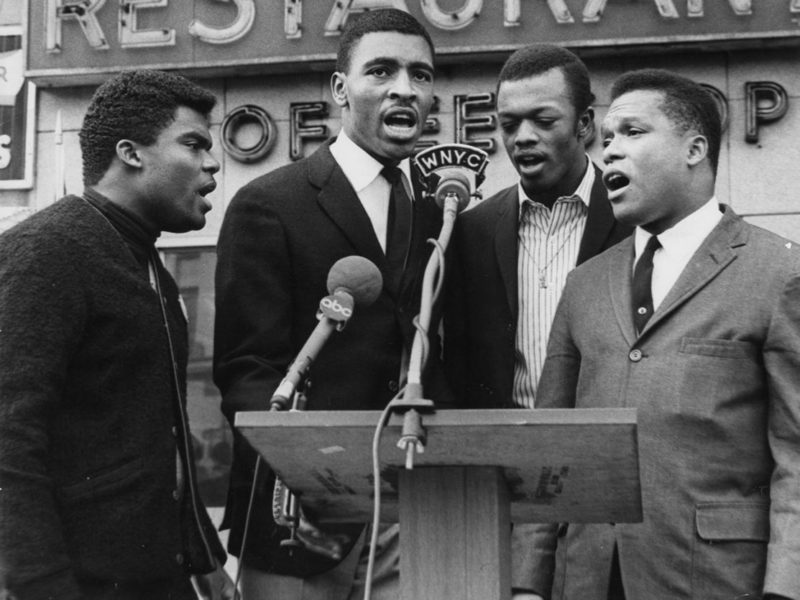

Here’s another one: What is common to the 2011 Tahrir Square protests in Cairo, the Estonian/Baltic Singing Revolution, the anti-apartheid struggle, and the US Civil Rights Movement? If you answered that they were all large-scale nonviolent campaigns that contributed to major social and/or political change, then you get one point. And you get a bonus point here if you answered that all of these movements featured communal performative events, such as choral singing, at campaign rallies.

How did you score? If you happen to have experience in organizing nonviolent campaigns (and a fair knowledge of pop, rock, and jazz), you probably did pretty well. After all, activists and scholars have long known—or assumed—that incorporating staged performances and shared cultural experiences into nonviolent campaigns can help mobilize support for, and participation in, those campaigns. While this idea may not be new, it has not previously been tested. Thus, in a study recently published in the Journal of Global Security Studies, we did just that by investigating whether nonviolent campaigns that feature staged events (which we call “spectacles”) and/or communal performances (“participatory performative acts”) are more likely to be large-scale campaigns. We find that they are.

How Performances Draw Crowds

In the study, we start from the assumption that nonviolent resistance movements are ordinarily underwritten by collective grievances, and a shared objective of redressing those grievances. Those concerns and goals motivate early-moving activists to mobilize for action. However, some individuals who are sympathetic to the movement’s goals may initially be wary of actively participating in street protests or other public resistance events—either because participation could come at a cost (e.g. loss of income, risk of arrest, or worse) and/or because they see that their individual contributions will not make a meaningful difference within the context of a mass protest. Where such views prevail, following the classic logic of Mancur Olson, nonviolent campaign organizers will struggle to mobilize large numbers of protestors unless they can find a way of offering exclusive incentives for individuals to participate.

We argue that help on that front sometimes comes in the form of staged shows and shared cultural performances at campaign rallies because such events provide emotional “rewards” that can only be experienced by individuals who are physically present at the rallies. Depending on the content of the concert or communal performance, that emotional reward can range from experiencing feelings of joy, empowerment, and solidarity alongside performances that lift spirits (e.g. “We Shall Overcome” as an anthem of the Civil Rights movement), through to catharsis alongside performances that invoke collective grieving (e.g. the anti-apartheid lament “Senzeni Na” (“What have we done?”)). Whatever the nature of the emotional release, however, it can only be experienced by individuals who are actually present at the campaign events that feature the concerts or communal performances in question. Following an online stream of Bad Bunny and Ricky Martin appearing before crowds of singing protestors who are calling for the resignation of Puerto Rico’s governor is just not the same as being there.

Based on this thinking, we propose that, where nonviolent campaigns offer participants the possibility of enjoying shared cultural experiences and associated emotional rewards, some sympathizers who are otherwise unsure about participation become more likely to participate. To make a first pass at assessing the merits of this claim, we identified the use of “spectacles” and “participatory performative acts” among a population of nonviolent campaigns between 1985–2013. We then looked at whether campaigns that featured such events more frequently were also more likely to be large-scale campaigns, and found that they were. Given the constraints of our data, we can’t say for sure whether performative events boost campaign size or, conversely, whether an increase in campaign size makes it more likely that these events will be organized. What we can say, however, is that staged shows and communal performances are an integral part of mass nonviolent resistance movements.

“Carnivals” Can Be Very Serious Indeed—Look at Sri Lanka

To appreciate the role that staged and communal cultural events can play in nonviolent movements, consider the protests that unfolded earlier this year in Sri Lanka, which called for—and ultimately succeeded in bringing about—the resignation of Gotabaya Rajapaksa as president, along with resignations of his family members and senior associates.

The protests were primarily driven by intense economic grievances, amidst fuel shortages, power cuts, spiraling inflation, and associated food insecurity. While those grievances underwrote an initial burst of street protests in late March and early April, they did not immediately translate into the sustained mass movement that eventually precipitated Gotabaya’s fall. However, resistance built over days, weeks, and months that followed, as artistic performances, music, street theatre, and shared religious acts became key components of life in a protest tent city that was established in the Galle Face Beach area of Colombo.

As performative aspects of the movement expanded, some critics dismissed the protests as a “beach carnival,” rather than a serious political campaign. However, as human rights advocate, Ambika Satkunanathan, wrote at the time: “Criticism… that protestors are not taking it seriously, that there is song and music… demonstrate a failure to understand the multi-faceted nature of protests and the fact that protests will always have those who come along for their own purposes.” Critics also failed to understand that individuals whose “own purpose” at Galle Face was to enjoy performative aspects of the protest process could still seek—and realize—very serious protest outcomes.

Despite facing state-sponsored violence and retaliatory street clashes, the largely nonviolent movement that persisted in Sri Lanka showed that campaigns which start small can build size, structure, and momentum through (hip hop and heavy metal) concerts, communal singing, and visual arts displays. That momentum meant that, when fuel shortages worsened in late June and July, there was an organizational framework in place around which mass mobilization could build quickly. Tens of thousands hit the streets of Colombo and, in mid-July, Gotabaya announced that he would step down. In keeping with the spirit of the movement, vindicated protestors sang in celebration, although the lack of more systematic political change since then suggests that, for now, Sri Lanka’s political future remains a song unwritten.

John Gledhill is Associate Professor of Global Governance in the Department of International Development, Oxford University. Allard Duursma is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. Christopher Shay is a postdoctoral research associate at the Human Rights Institute, University of Connecticut and an International Security Program Fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School.