Guest post by Marianne Dahl and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch

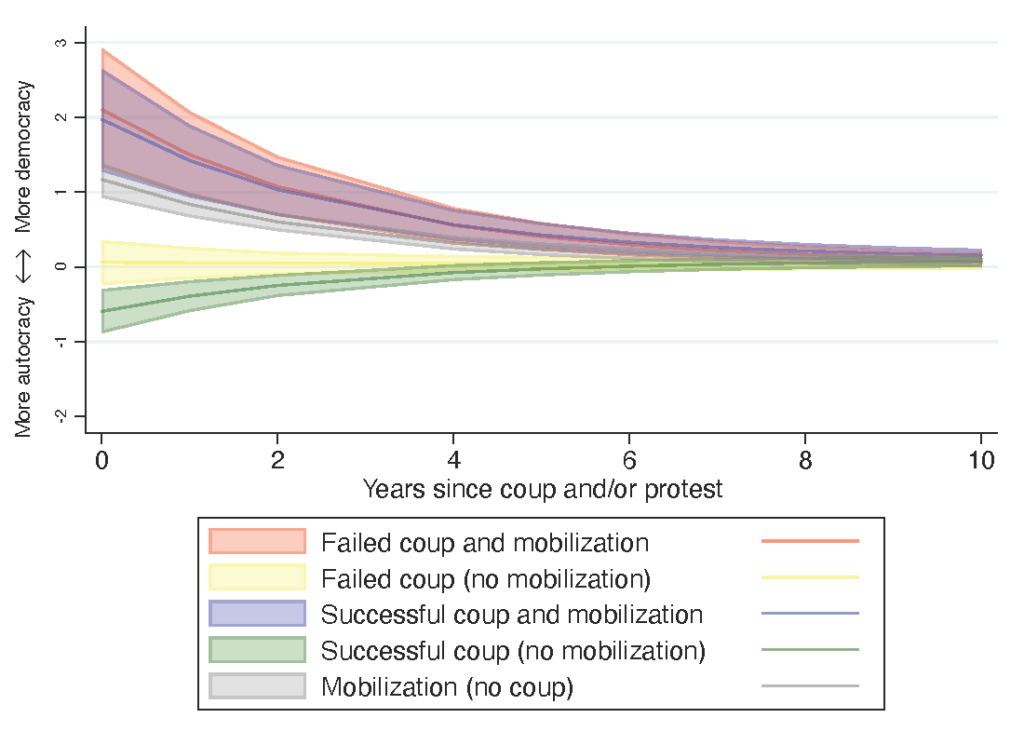

Some have suggested that military coups are the best hope for removing autocratic leaders and promoting democracy. Others contend that coups are more likely to spur increased repression and new autocratic regimes, undermining hopes of democratic reform. There are certainly historical examples where coups have preceded democratic reform—take for example the 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal. But coup attempts have also ushered in harsher autocratic rule, such as in Equatorial Guinea after 1968. The empirical record shows no clear or consistent relationship. A look at changes in Polity democracy scores, a common comparative measure of democracy and political transitions, shows that although political change is much more likely after a coup, moves towards democracy and autocracy are about equally likely.

In a recent article in the European Journal of International Relations, we argue that what happens after a coup hinges on popular mobilization. Democratic reform is more likely when coups occur in the context of popular mobilization, and autocratic entrenchment is more likely in its absence.

Considering leader incentives after coup attempts sheds light on why coups spur democratic reforms at times and autocracy at others. Both failed and successful coups leave political rulers in a challenging position. A coup reveals divisions among elites and is likely to exacerbate competition. It is often unclear who remains loyal and how much support an incumbent can count on. There is a high likelihood of new coup attempts, and rulers challenged by a coup are more likely to be exiled, jailed, or executed.

Rulers can respond to these challenges in different ways. They can try to annihilate threats or repress opposition. Increasing control through repression and purges is often an autocrat’s preferred response. But such strategies can be fraught with risks. Potential threats can be difficult to identify, and harsh repression can backfire and fuel opposition.

An alternative strategy is to promise democratic reform. Promises of reform can help enhance a leader’s appeal, and it is difficult to claim popular consent for seizing power in a coup without promising elections. Moreover, free elections and respect for political rights are increasingly held up as conditions for avoiding economic sanctions or securing external aid. Democratic reform can also allow rulers to establish a safer exit route should things not go their way. One out of three leaders who lose power in a coup are imprisoned or killed within the next year, but only one out of fifty leaders who lose power in elections face that fate.

Whether leaders choose repression and autocracy or democracy and elections depends on the presence of popular nonviolent mobilization. Popular mobilization—public protests, sit-ins, acts of defiance to orders, and strikes—decreases the viability of repressive strategies and increases revolutionary threat.

Coups reveal cracks within a regime, which popular mobilization can leverage and deepen. Further, a fractured regime is more vulnerable to popular mobilization. Divisions among elites can increase citizens’ expectations of success and encourage wider participation, resulting in more effective threats. Popular mobilization therefore increases a coup leader’s incentives to promise democratic reforms. In the risky aftermath of a coup attempt, incumbents may try to reach out to a mobilized opposition or the general population to increase their popularity and contain threats from elites. In this context, democratic reforms can decrease the risk of a new coup, since coup attempts are more likely when incumbents are less popular.

By contrast, leaders who do not face threats from mass protests have fewer constraints to repress or selectively accommodate potential coup-makers and less need to seek broader support. Repressive strategies are especially likely after successful coups without mobilization because repression is easier to enact after a display of power in seizing control, with at least the tacit support of security forces. In contrast, failed coups leave an incumbent weakened, with worse prospects for consolidating power.

Of course, popular mobilization by itself can trigger political change, and coups and mobilization may have common causes. Our article, which provides systematic empirical analyses using data for the period 1950–2019 on coups, mass mobilization, and changes in the level of democracy, shows that popular mobilization makes changes toward democracy more likely after a coup. In the absence of mobilization, successful coups are more likely to result in changes toward greater autocracy.

Coups and political disruptions happen all over the world, and their occurrence presents an opportunity for reform—towards democracy and openness—or away from democracy and towards further repression. The transition to democracy after the coup in Portugal was not a foregone conclusion, rather, popular mobilization helped steer the country toward a political transition. Although hope for a democratic transition in Sudan after the military coup ousting Bashir in 2019 was undermined by military rulers backtracking on promises, continuing protests make it more difficult to secure autocratic rule. Popular protests helped bring down the 1991 coup attempt in the Soviet Union and preceded a period of subsequent democratic opening in Russia. And if there were to be a coup against Putin, the prospects for subsequent democratic reform seem much better with popular mobilization than without.

Marianne Dahl is a senior researcher at International Peace Research Institute Oslo. Kristian Skrede Gleditsch is the Regius Professor of Political Science in the Department of Government at the University of Essex and a research associate at the Peace Research Institute Oslo.