By Andrew Kydd

There has been a lot of coverage recently discussing the possibility of a terrorist attack at the Sochi Olympics and the effect this threat is having on athletes’ families and other sports fans who are worried about attending. I was recently interviewed on local TV on the subject, but had not really formulated my thoughts coherently and so gave somewhat inconsistent answers. Now that I have had time to think about it, I am happy to say I can present my opinion in a new and improved, fully coherent and definitively inconsistent fashion. In the end, I’m not sure there’s an easy answer to the question of should you stay or should you go.

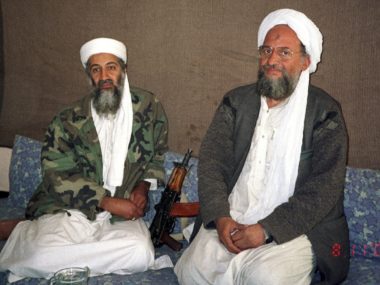

- The likelihood of a terrorist attack in Sochi is relatively high. There is an existing Salafi terrorist organization in the region that has shown interest in attacking the Games. This stands to reason — the Olympics may well be the biggest public event in the world, televised to billions. There is also the Munich precedent, in 1972, when PLO terrorists killed eleven Israeli athletes. The Boston Marathon last year showed how individuals in the Chechen diaspora, even without much training or organizational support, can become radicalized to the point of launching terrorist attacks against sporting events. Sochi is physically close to the North Caucasus region. Therefore it seems almost certain that there will be attempts. Whether any of them succeed will depend on the effectiveness of Russian security. This will certainly be much higher than normal, but the difficulties involved in securing thousands of square kilometers and screening millions of people suggests that the task will not be easy. As the cliché goes, the defense needs to succeed everywhere all the time, the offense needs to succeed only once.

- The likelihood of any specific person dying in a terrorist attack in Sochi is nonetheless quite small. Terrorist attacks generally do not kill many people. The Boston bombing killed 3 and caused 14 amputations. The recent bombings in Volgograd killed 34. One hundred fatalities would be quite high for a terrorist attack. Organizers hope to sell a little over a million tickets at Sochi. A terrorist attack killing one hundred of those million spectators will produce a casualty rate of one in ten thousand. By way of comparison, this is about the same rate as the US automobile fatalities (30,000 per year, out of 300,000,000 people). So if you are ok driving, you should be ok going to Sochi, if the chance of dying is the main issue.

- If a terrorist attack kills one hundred people in Sochi, no one will (in retrospect) have had a good time. This might be called the “pall effect.” There will be the fear and anxiety, the increased security hassle, the delays and cancellations. Perhaps more importantly, at a basic emotional level, no one will feel good about having a good time at an event where 100 people perished in a terrorist attack. Humans are very good at compartmentalizing. We allow ourselves to have fun even though we know that on every single day people around the world, in our country, and in our home city, are suffering and dying in horrible ways. But when an event is too closely associated with us, we do not compartmentalize and adopt a shared perspective. Few people who attended the Boston Marathon probably say afterwards that they had a great time and thought it was a lot of fun, except for those people who were injured or killed of course. Hence, even if few people are actually directly affected by a terrorist attack, everyone will retrospectively be unable to have enjoyed the experience.

- To not go to Sochi because of the fear of terrorism is to let the terrorists win. This is another post 9/11 cliché, back then we were told that not doing anything we wanted to do was a victory for Bin Laden. But there is a sense in which not going to the Olympics because of fear of terrorism is to accord them power well beyond their actual capabilities, and hence to, in effect, help them achieve their agenda in however small a way. One qualifier here is that many people may feel the Chechen conflict is not their fight. If Russia wants to locate their Olympics near a long simmering ethnic conflict with plenty of faults on both sides, it’s not really the rest of the world’s concern that the terrorists be defeated. On the other hand, the current Chechen terrorists are heavily tied to the global Salafi network, and have already inspired one attack in the US, so Americans may feel it is partly of our fight.

- To go to Sochi is to validate Vladimir Putin’s repressive regime. This is a long-standing problem in Olympic ethics, of course, most recently exhibited in China. However, the Chinese had the sense to locate their Olympics in Beijing, rather than some small town just outside of Tibet. So while everyone complained about the air quality and general lack of freedom, the worst tendencies of the Chinese regime were tactfully off stage. Putin has made a few minimal pre-Olympic gestures, like releasing Mikhail Khodorkovsky and members of Pussy Riot, but these are lost in the boom of the anti-gay drumbeat, possibly the only issue over which Putin and Chechen Salafi jihadists are in complete accord. Putin has assured gays that they will be welcome in Sochi, so long as they stay away from the kids. Nice. It’s also harder to make the “it will help open up the regime” argument, since Russia was open, and Putin is busy shutting it back up again.

So that’s it, the political, ethical, and strategic considerations cut both ways. At least it should be easy to get tickets.

0 comments