By Christian Davenport and guest contributors Adrian Arellano and Kiela Crabtree

Amidst prolonged protests in cities across the United States, many are asking if the swell of political activity ignited by anti-black police violence is similar—or not—to anything historically. Is it 1968? Is it 1991 when Rodney King was beaten by the LAPD? Is it the 1935 Harlem riot? Or, is it something completely different? Without a useful reference point, ordinary citizens, activists, and policymakers are somewhat at a loss for how to understand underlying causes, similarities or differences, and evaluate attempts at resolution.

Right now, we can’t say for sure which period is the most comparable to what we are seeing throughout the US, in part because the current uprising is not yet over. But we do have access to one of the periods that people have been talking about. In an effort to assist in the current discussion, we offer data collected and analyzed by the Radical Information Project, which has been examining data about the 4,052 disturbances, uprisings, riots that took place between 1968 and 1972, originally compiled by the Lemberg Center for the Study of Violence. Our hope is not only to provide insights into earlier uprisings but also to offer suggestions about what data should be compiled now—or the next time—a protest or uprising, and policing of it, takes place.

This is what we discovered.

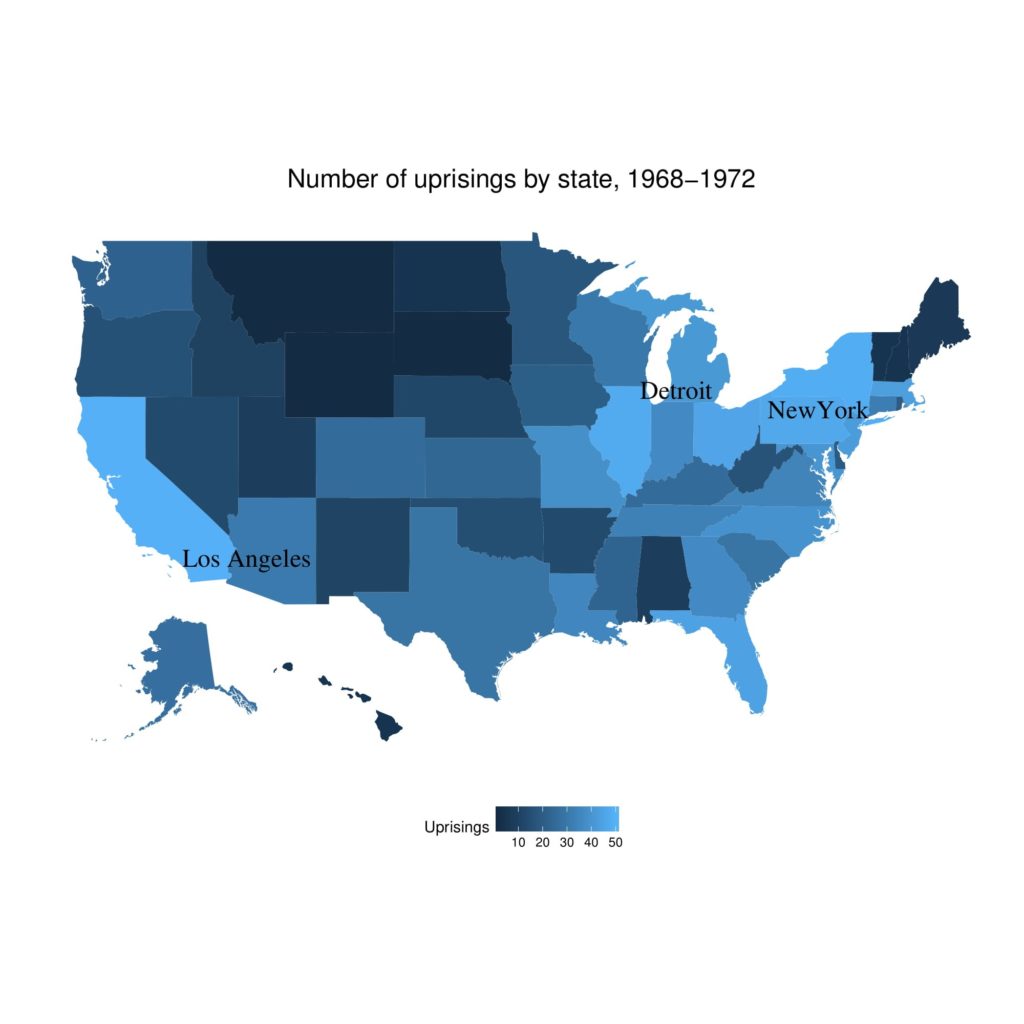

Similar to current activities, uprisings took place all over the United States, with 960 cities having an event in 48 states and Washington, DC. The vast majority—78 percent—lasted six hours or less. The longest lasted for 14 days in Montclair, NJ (1968) when the Black Student Union successfully demonstrated after a change in faculty leadership of the organization. We are seeing events now that are longer and more widespread.

Some cities had more uprisings than others. Unsurprisingly, and like today, many were concentrated within the cities of Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, and Washington DC—594 events took place within these four cities out of 4,052. However, also similar to the current period, other cities such as Denver, New Orleans, and Hartford, CT witnessed disturbances as well.

The amount of property damaged varied significantly. About 57 percent, or 2,300 events, featured some type of property damage. We are not yet sure how bad this is in the current period but there will likely be lawsuits and insurance claims filed that will assist us.

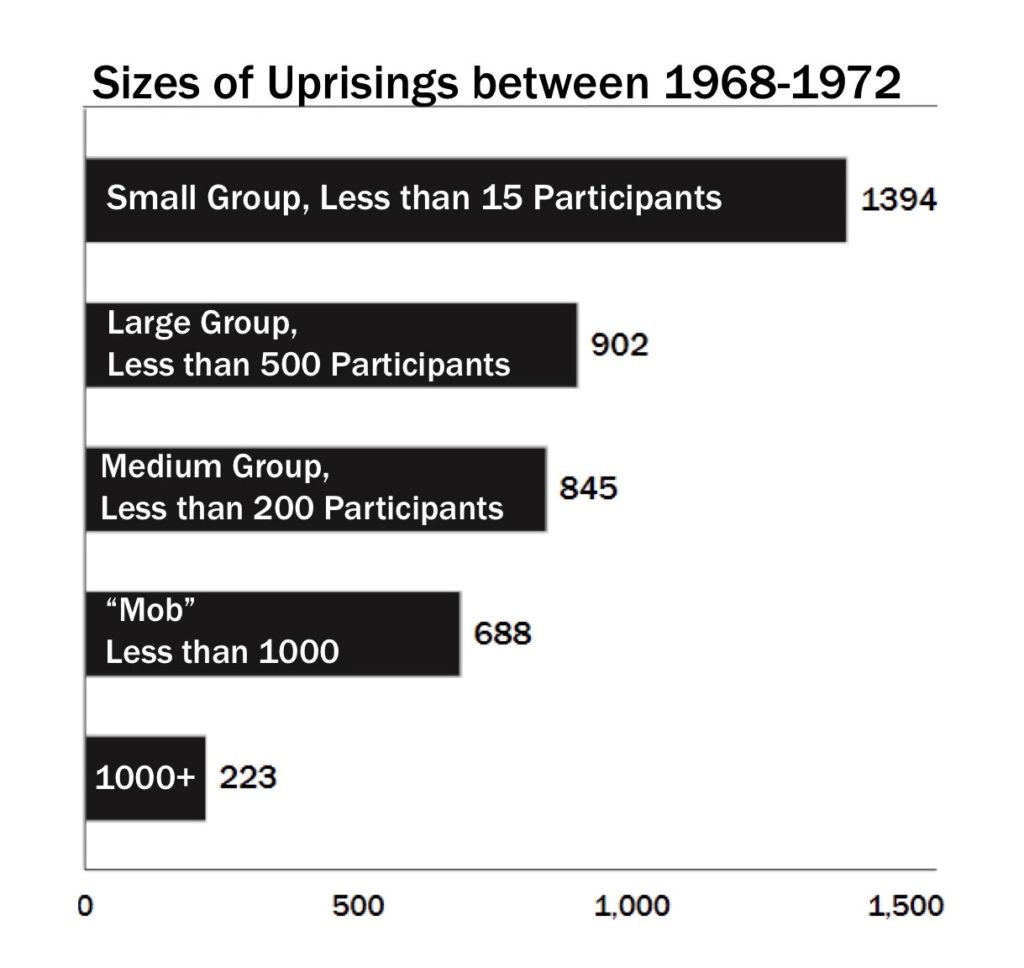

The size of the uprisings varied. Most large protests—defined by Lemberg as those with more than 1,000 participants—occurred in New York, Illinois, California, Maryland, and DC. In addition, most of the large events occurred in 1970—about 90 compared to the 36 in 1968, although overall, 1968 experienced more disturbances than any other year. By some accounts, these numbers may have been exceeded by some of the largest events recently.

Some uprisings were quite lethal. Over 300 deaths were reported in about 175 disturbances. The deadliest event occurred during the Attica prison uprising in 1971, when at least 43 people died, as depicted by our colleague Heather Ann Thompson’s great book, Blood in the Water. This differs significantly from the current uprising, where to date 21 people have died.

There were many injuries between 1968 and 1972. Indeed, this is the most common outcome from uprisings, with more than 50 percent of events reporting an injury. For example, more than 1,000 people were injured in DC alone during the five days protestors took to the streets after the assassination of Martin Luther King.

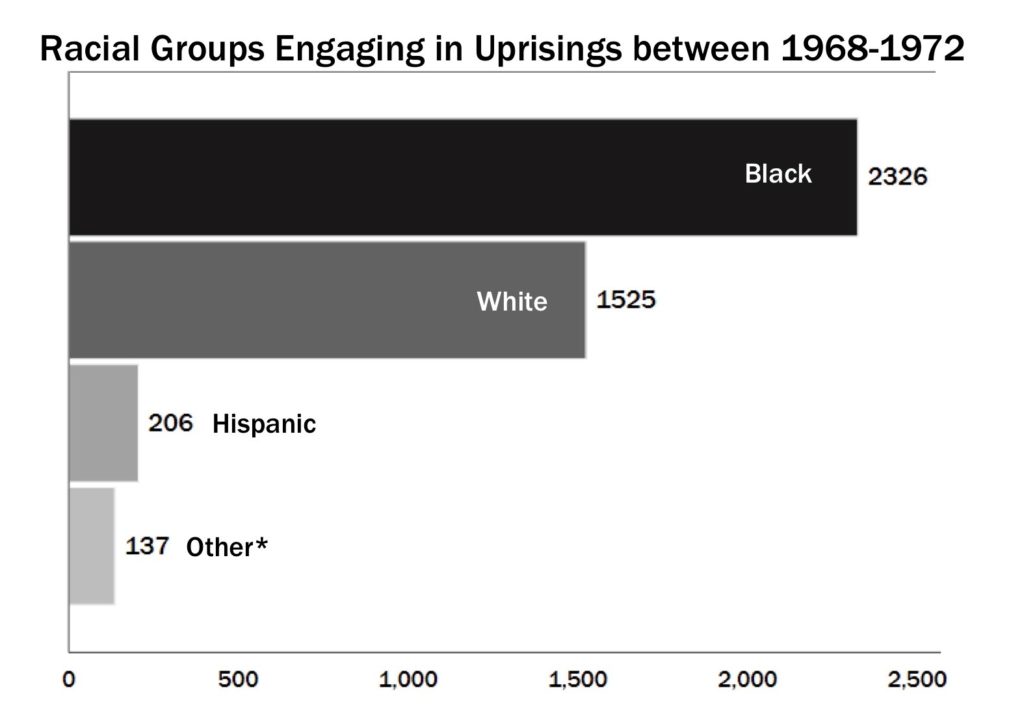

The events mostly involved African Americans but a decent number involved whites and Latinos. In the current uprising, the pattern of racial group involvement might have been similar, initially, but it is definitely not reflective of what we are seeing most recently (i.e., protests are more diverse now).

Similar to the current episode of contention, many uprisings took place in schools but comparable amounts took place out in the streets and at businesses.

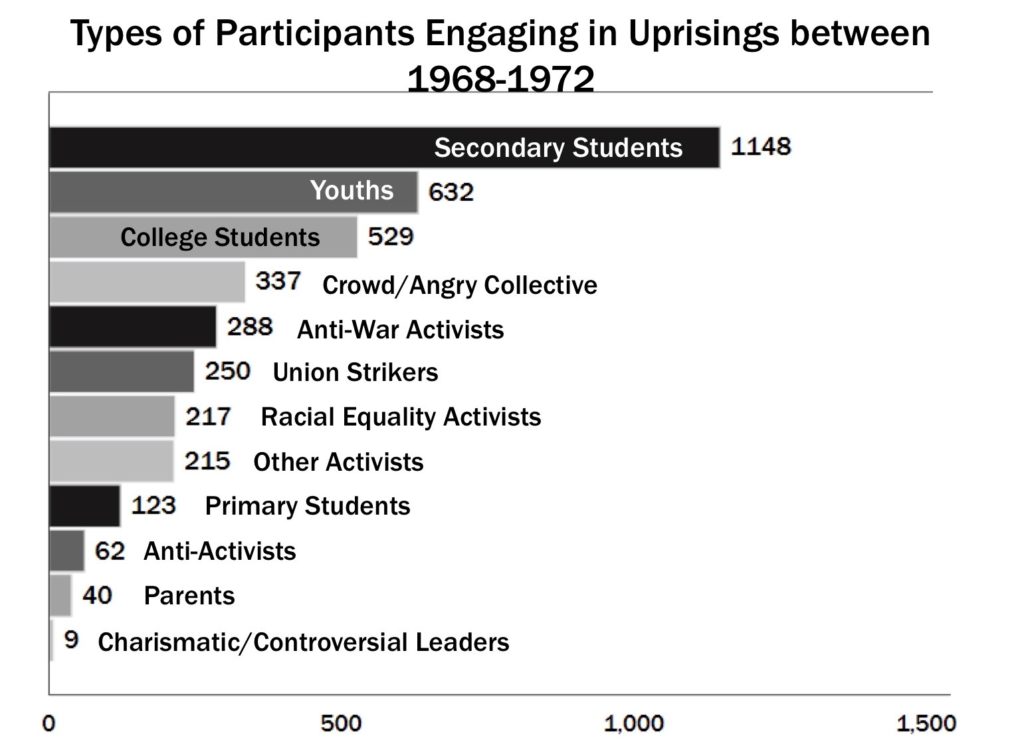

A large number of participants were young people. It is unclear what the age composition of the current events might be.

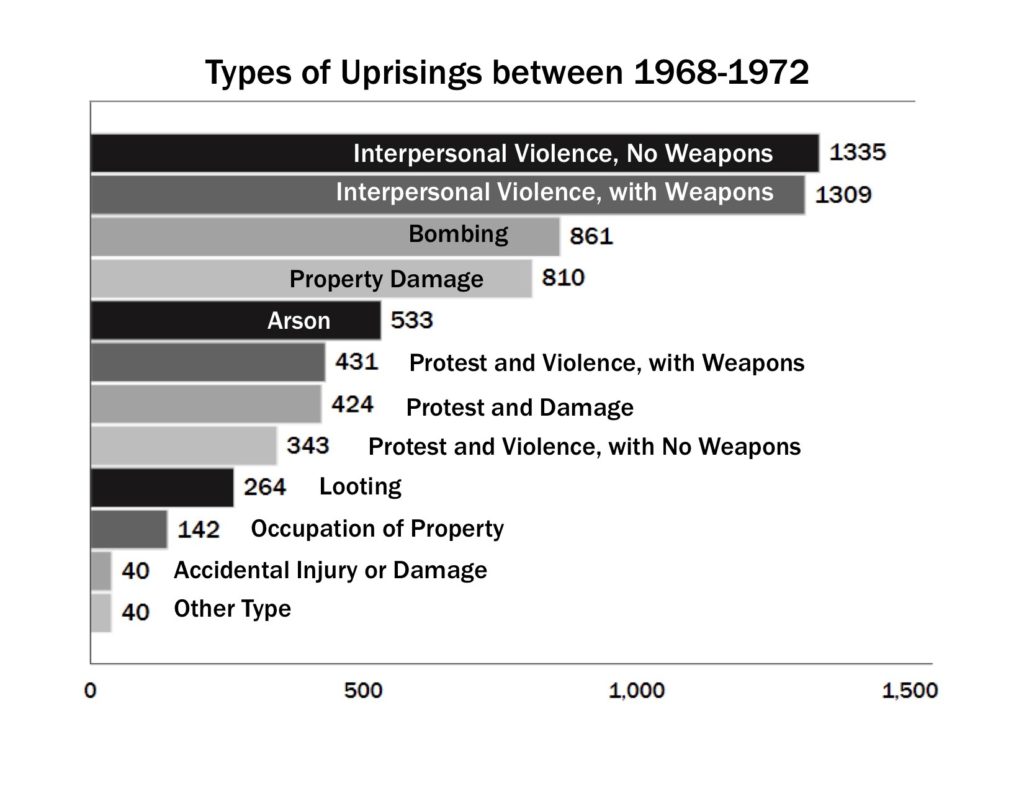

What did people do at the protests? There was a fair amount of interpersonal violence, with and without weapons, a few bombings and property damage, but very little looting overall. Indeed, looting only occurred in 6.5 percent of disturbances, or about 260 instances. New York City experienced about 240 disturbances yet only 21 of those featured looting. This prompts us to treat as cautious current reports about looting, as it was historically such a limited occurrence in one of the most frequently discussed periods of uprising in US history that is believed to be comparable.

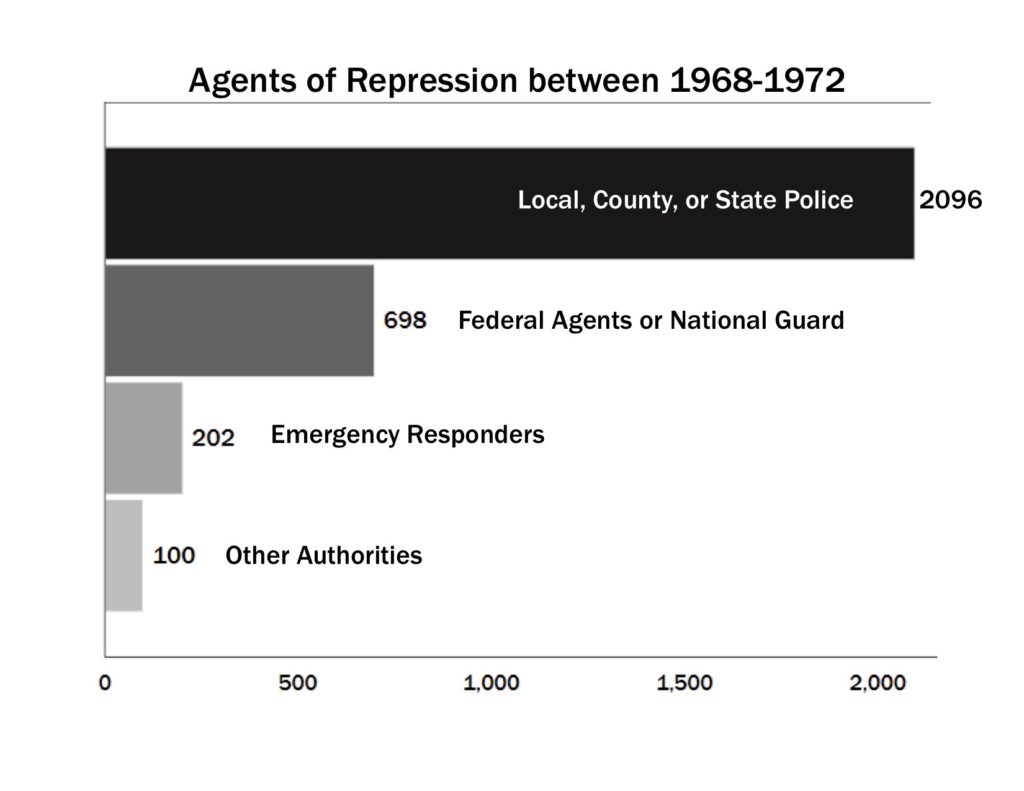

Directly relevant to the topic of police response to protest, authorities responded coercively/forcefully to relevant events in 68 percent of cases with local or state agents usually responding. The most common types of responding agents were from local police (51 percent of cases), state troopers (6 percent), and sheriffs (4 percent). Federal agencies responded only about 3 percent of the time and mostly through the deployment of the National Guard. This may be a big difference from the current period where there appears to be more jurisdictional swapping taking place—i.e., federal authorities assuming responsibility for policing over local authorities. Future research would do well to pay attention to such things.

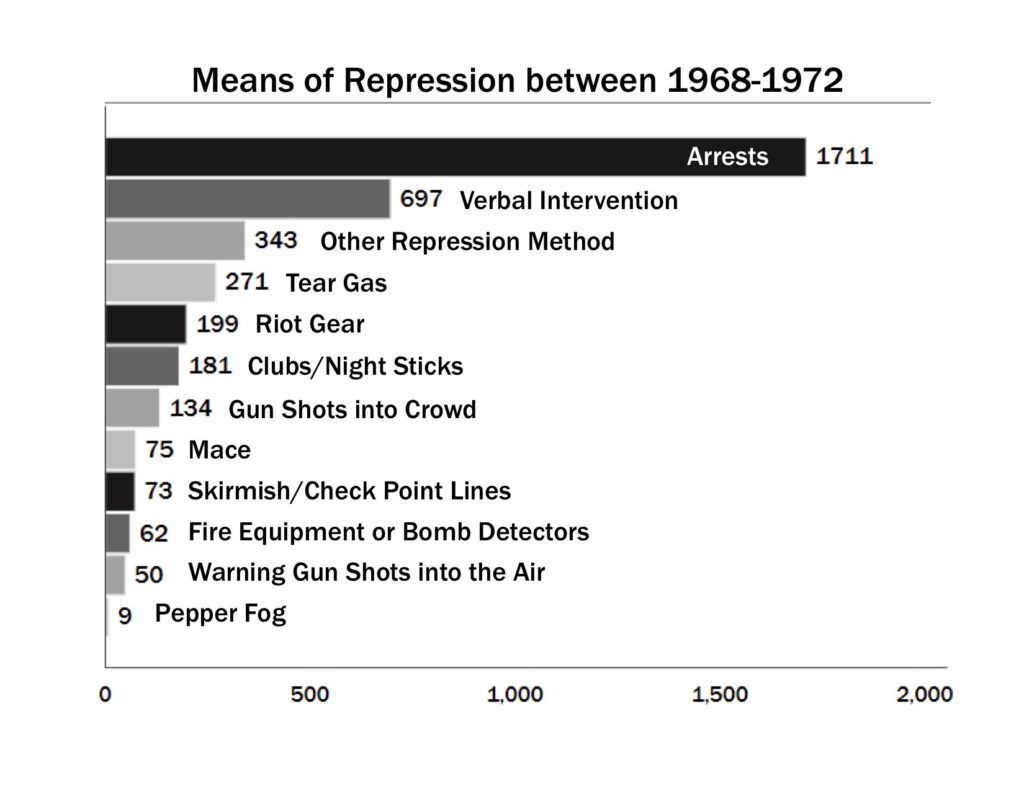

There were many arrests with 47.2 percent of uprisings featuring this behavior. There were also a variety of other tactics employed: verbal intervention, the use of riot gear, check points, gunshots in the crowd, use of mace, use of tear gas along with the use of clubs/nightsticks and warning shots in the air.

Was the period between 1968 and 1972 more or less violent? We need the data on the current wave to make this evaluation. Right now, several groups are collecting examples of disproportionate police responses to the protests against police brutality. Criminal defense attorney T. Greg Doucette, for example, has compiled hundreds of instances of “unnecessary violence by law enforcement officers against civilians.” Other efforts to map Black Lives Matter protests are underway.

Of course, an arrest does not tell us how many people were arrested. From the data, we see that the number of arrestees is quite high occasionally. In one event alone during the spring of 1971, 7,000 people were arrested in an anti-war demonstration in Washington DC. This seems to differ from the current episode—there have been arrests but nothing close to the 1968-1972 period.

The actions of those engaged in uprising between 1968-72 and those engaged in the policing of this behavior, are in some ways comparable to the current period. In other ways, however, they are quite different. As we move forward to evaluate and understand what is taking place—and what should take place, we would be well served to think through these similarities and differences. They reveal the problems that are more or less institutionalized, and resistant to change.