Guest post by Ariel I. Ahram.

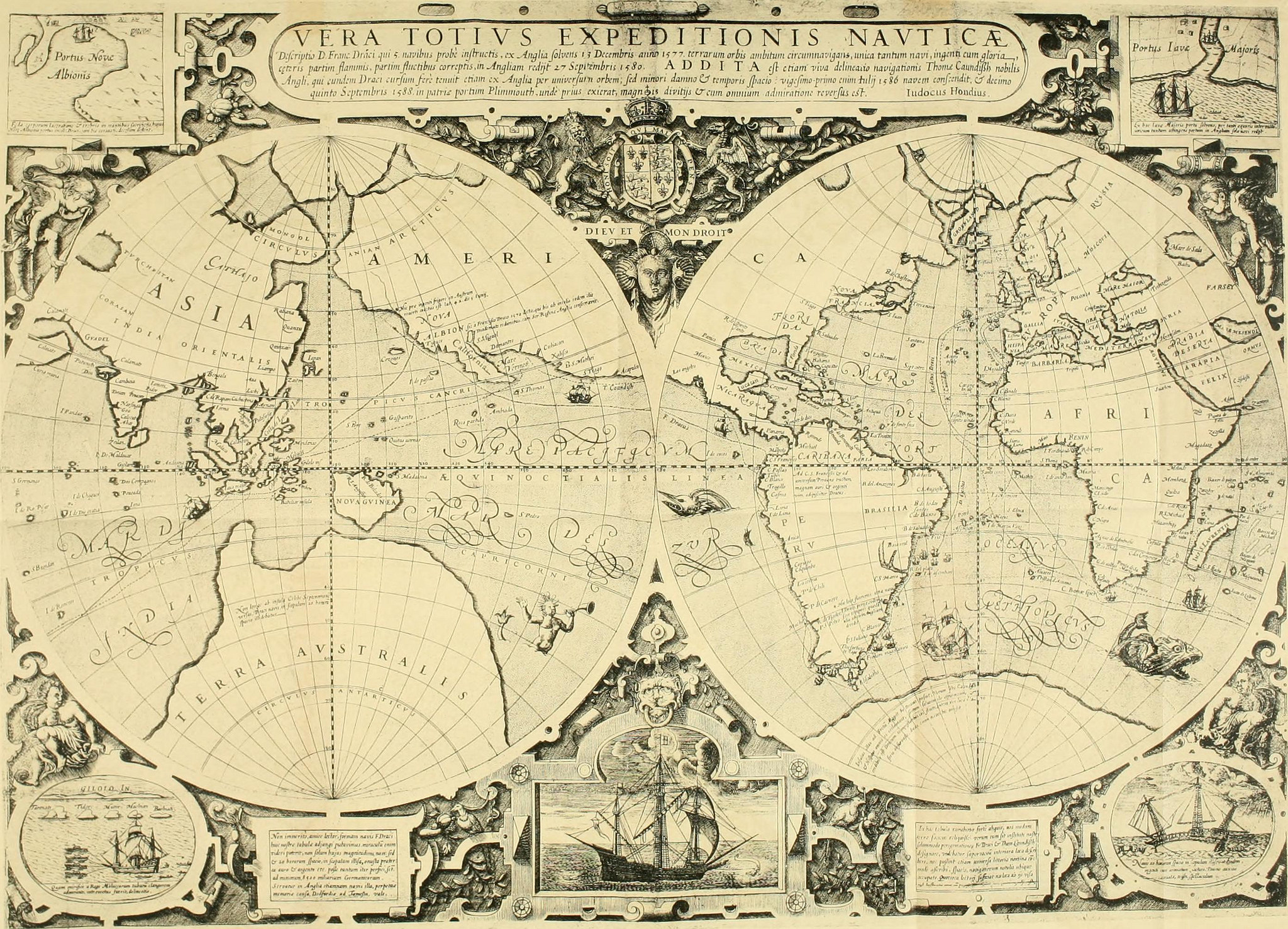

The Islamic State has gained the most attention for its bid to destroy existing state boundaries in the Middle East and hasten the “end of Sykes-Picot,” the colonial agreements that demarcated state borders in the region. Curiously, this view is echoed by one of the US’s closest allies in the region—the federally-autonomous Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq. KRG President and head of the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP), Massoud Barzani, has repeatedly declared Sykes-Picot to be artificial and defunct. As he told the Arab newspaper al-Hayat, “The new borders in the region are those drawn in blood, rather than the Sykes-Picot borders.” The Kurds were left out of consideration when the colonial powers devised regional boundaries and consequently saw their territories divvied up between Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Now is the time to redress this mistake. Barzani himself was born in 1946 in the State Republic of Kurdistan in Mahabad. His father, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, led a band of Kurdish fighters from Iraq across the border to support Kurdish rebels that had managed to carve out an area of territorial control over northwestern Iran. The Republic lasted less than a year before it was deserted by its Soviet patron and overrun by Iranian forces, but it remains a crucial symbol of unity and self-determination. As Barzani himself said, Mahabad was the “ideal time and place to be born a Kurd.”

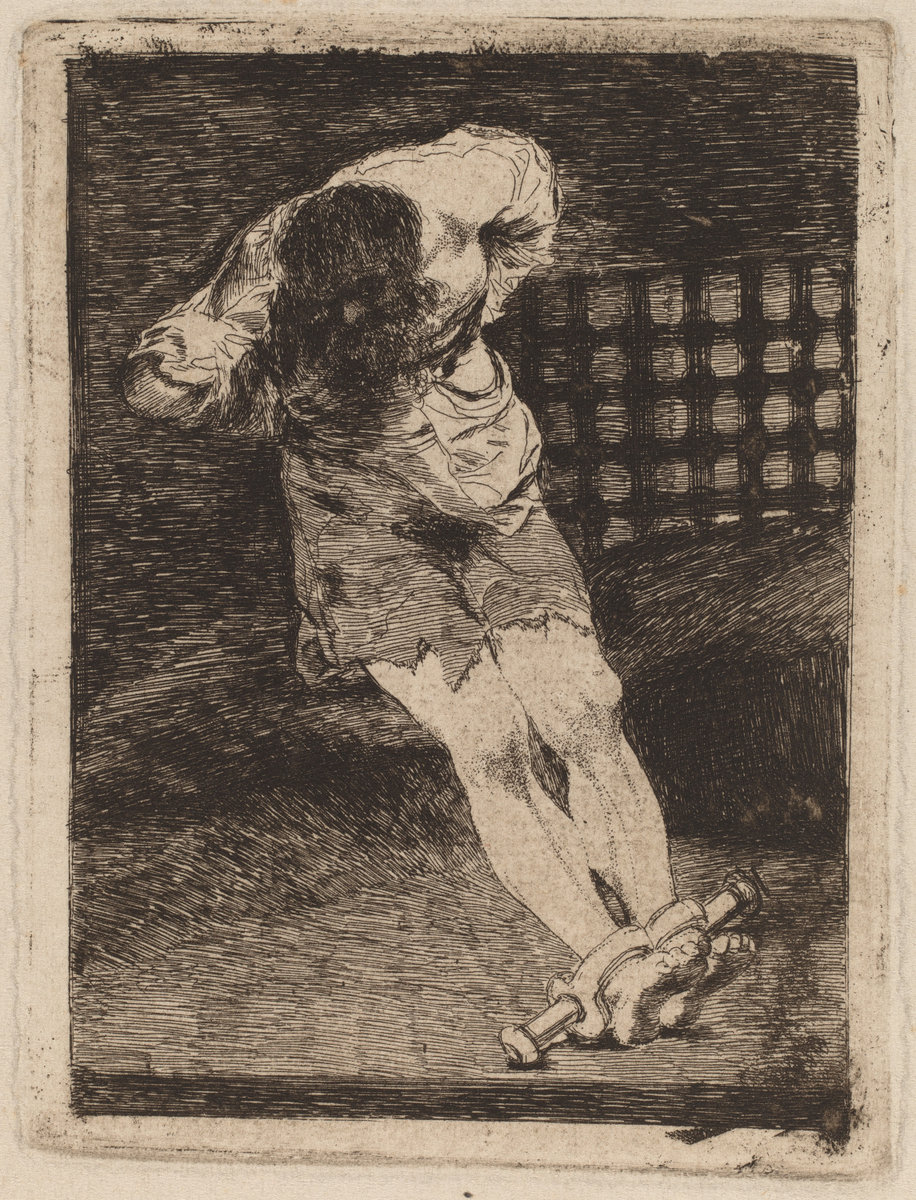

Since late 2014 Barzani has been readying the KRG for a popular referendum on statehood in Kurdistan, to be held sometime in 2016. Barzani clearly favors secession. Barzani’s rhetoric reinforces nationalist sentiment among Kurds and invokes international norms of self-determination. Cynics say the referendum is meant to distract from the KDP’s own struggles and failures. The Gorran (“Change”) Movement has made significant headway as an electoral opposition movement, criticizing the KDP’s corruption and calling for constitutional limits on presidential authority. In October 2015, KDP forces began a crackdown on Gorran protesters, media outlets, and parliamentarians. The Kurdish region as a whole faces worsening economic conditions as well. Erbil and the central government in Baghdad have been in a protracted dispute over the disposition of oil revenues derived from the northern fields. After the KRG began selling oil without Baghdad’s authorization, the central government suspended the transfer of oil funds completely in early 2014. The global drop in oil prices dealt a body blow to both Baghdad and Erbil. The problem is compounded by the KRG’s precarious security position. The Islamic State’s 2014 offensive on Mosul put enormous strain on the KRG peshmerga (military forces). Around 1,000 troops were killed as the Kurds moved to defend areas north of Mosul and Sinjar. The peshmerga receive support from U.S. airstrikes and training programs and are poised to play a key role in the planned assault on Mosul. Yet the peshmerga haven’t been paid in several months and their equipment and readiness remain substandard. The fighting itself has caused some 1.8 million Iraqis, mainly Arab Muslims and Christians, plus 200,000 Syrian Kurdish refugees, to flood into the KRG, further straining scarce resources.

A key question regarding the referendum is what territory it covers. Iraq’s 2005 Constitution – in Article 140 – specifies that the government should conduct a census and hold a referendum in Kirkuk and other disputed territories to determine whether the people in these areas wish to accede to the KRG or remain under the jurisdiction of the central government. Kurdish leaders claim that Kirkuk and other areas were historically part of Kurdistan. Saddam Hussein’s ethnic cleansing and encouragement of Arab transmigration in the 1970s and 1980s tilted the demographic balance against them.

With large oil fields in its outlying regions, Kirkuk in particular became a flashpoint after the removal of Saddam in 2003. The KRG dispatched forces to the area in order to facilitate the “return” of displaced Kurds. The central government relied on local Arab and Turkomen forces to thwart Kurdish advances. The constitutionally-mandated census and referendum was postponed indefinitely. When ISIS advanced on Mosul in 2014 and the Iraqi army retreated in disarray, the Kurdish troops took control of the entirety of Kirkuk and significant portions of Nineveh, Erbil, Diyala, and Wasit provinces.

The KRG claims that the referendum is necessary and appropriate because of the failure to enact the provisions of Article 140. It disavows any intention to annex the disputed territory without popular consent. The disputed areas might have a separate referendum about whether to join a Kurdish political entity. In the meantime, though, the KRG has refused to stand down or allow the Iraqi army and allied militias to enter the disputed territories. For its part, the central government deems these actions unconstitutional and of no legal consequence. Still, the peshmerga remain significantly more capable than the Iraqi security forces and the PMU and enjoy a clear strategic advantage. Functionally, the Kurds could do away with nearly all their ties to Baghdad.

Yet statehood hinges less on facts on the ground than perceptions from abroad. While Barzani likens the Kurdish quest for independence to “Scotland, Catalonia, Quebec and others” who “have the right to decide their future,” many in the international community see ominous parallels to the Balkan civil wars of the 1990s. The KRG has carefully cultivated external allies in efforts to demonstrate its potential as a pillar of stability in a chaotic region. To the US, the Kurds tout their service in the war on terror and their record of democratic elections. The KRG also has good political and commercial relations with Tehran. In recent years the KRG has even built strong ties to Ankara (largely through joint oil projects). Moving from de facto autonomy to legal sovereignty may be a bridge too far for these external allies, however. The U.S. holds stubbornly to a “one Iraq” policy. Iran probably prioritizes its relationship with the Shi’i-dominated regime in Baghdad more than Erbil. For its part, Turkey has long been worried that Kurdish separation from Iraq might embolden its own restive Kurdish population. Overall, then, the diplomatic response to Kurdish independence remains ambivalent at best. Even if the referendum affirms the popular demand for statehood, the international community is unlikely to grant recognition, effectively forcing Kurdistan back into its unhappy cohabitation with Baghdad.

But the referendum has the potential to transform the KRG’s domestic politics. Given the number of Arabs, Turkomen, and other non-Kurds in the disputed territories and the original Kurdish region, the agglomeration of these territories would dilute the Kurdish majority and redefine notions of national identity and citizenship. The accession of non-Kurds, making up around a quarter of the total population, within Kurdistan could bring about a shift from a largely ethnically-based identity that marginalizes non-Kurdish minorities into a multi-ethnic identity focused on civic affiliation. Kurdistan may be for the Kurds, but it will also have to be for other citizens as well. Moreover, voting solely within the Iraq’s Kurdish Region (and KRG-controlled territories) signals the end of the romantic ideal of greater pan-Kurdish unity. The KDP in particular has had a contentious relationship with Syrian and Turkish Kurdish factions associated with the PKK, which effectively controls its own enclaves in eastern Syria. Limiting the referendum to Iraq alone effectively forecloses the hope of larger unity. The path to statehood remains bounded by the very borders that Barzani would seek to overturn.

Ariel I. Ahram (@arielahram) is Associate Professor at Virginia Tech’s School of Public and International Affairs in Alexandria, VA. He is the author of Proxy Warriors: The Rise and Fall of State Sponsored Militias (Stanford, 2011).

2 comments