By Andrew Mack

A greater percentage of conflicts are brought to a halt through negotiated settlements today than at any time since the end of World War II. But about a third of all peace agreements break down in less than five years, leading some critics to worry that negotiated settlements are an ineffective means of dealing with civil conflicts.

The critics are wrong.

Different forms of negotiated settlements — i.e., ceasefires and peace agreements — have different risks of failure. Peace agreements, unlike ceasefires, include concrete steps to resolve the issues over which the conflict is being fought. As might be expected, the peace agreement failure rate is lower than that of ceasefires. Between 1950 and 2004, 32 percent of peace agreements were followed by recurring violence, compared with 38 percent of ceasefires.

Even though this is a significant failure rate, it is important to remember that two thirds of peace settlements hold with no resumption of conflict. And, as the last Human Security Report pointed out, there is evidence to suggest that peace agreements became more stable — i.e., less likely to recur — in the new millennium.

When we read that peace agreements have “failed,” we might conclude that the peace process is reversed entirely and the affected country relapses into full-scale war with no diminution of death and destruction. The evidence indicates that this is not the case.

When renewed violence occurs after a peace deal, it is sometimes started by rebel groups that never signed the agreement in the first place. In other cases, only one of several signatories resumes fighting. The data show that when just two warring parties sign a peace agreement they rarely go back to war with each other––despite the presence of spoilers.

But there is an even more telling rebuttal to the critics of peace talks and negotiated settlements. Wars that restart when peace agreements fall apart almost always experience a significant reduction in death tolls. In 10 out of the 11 collapsed peace agreements between 1989 and 2004 the annual death toll was lower after the conflict restarted.

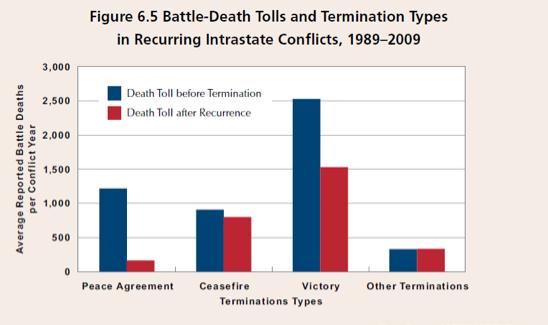

As Figure 6.5 (from the forthcoming Human Security Report, 2012) demonstrates, the reduction in deadliness associated with conflicts that start when peace agreements fail is very large. The average annual death toll of civil conflicts drops by more than 80 percent if they recur after a peace agreement. The percentage decline is only half as big for victories, while death tolls for ceasefires and other terminations show little change.

Peace agreements, in other words, save lives, not only by stopping hostilities, but also by dramatically reducing fatalities if the fighting recurs.

Note: This post draws on an analysis of the recurrence of civil wars undertaken by Sebastian Merz , of the Human Security Research Project (HSRP) at Simon Fraser University with additional research by HSRP staff. The full analysis will appear in the forthcoming Human Security Report, 2012. The data are from Uppsala University’s Conflict Data Program.

9 comments

This is a novel and very interesting finding. Thanks for sharing it with us.

I think this is a really interesting post. However, as a non-expert on the subject matter (peace agreements/war termination), I could not help but question the conclusion that “Peace agreements, in other words, save lives, not only by stopping hostilities, but also by dramatically reducing fatalities if the fighting recurs.” My hunch is that this finding may have more to do with factors that make peace agreements more likely rather than anything to do with agreements themselves. Has anyone done any work on this or seen anybody sort out this issue?

What Andrew didn’t write in this post (but which I am sure will be mentioned in the longer version of the report), is the curious relationship between conflict duration and peace agreement. That is, while it is often assumed that parties will “fight it out” if no peace agreement is signed, the reality is that victories are almost always only registered in the beginning of a conflict – while peace agreements usually are signed after several years (or, sometimes, decades) of fighting.

So, parties first “option” is to push for victory and only if this fails will there be seriuos negotiations and the possibility of a peace agreement. This has two implications: first, the post-conflict environment after peace agreements is usually more difficult than after victories. Second, the options for ending a long-running civil war are rarely peace agreement/victory, but peace agreement/continued fighting…

Thomas

I think that your point is true almost by definition––i.e., the positive factors that make peace agreements possible in the first place will likely help keep fatalities low if the agreements break down. Plus many of the “failures” may be due to relatively small outbursts of violence from “spoiler” factions in one or more of the parties who never favoured the agreement.

Joakim

Yes your important point is addressed in the Report. You are cited!

David

You are absolutely right re. Luttwak. We critiqued his provocative–-and wrong–– Foreign Affairs article back in 2006. See: http://hsrgroup.org/docs/Publications/HSB2006/2006HumanSecurityBrief-FullText.pdf p.22

Andrew Mack

i.e., Luttwak was wrong.

Thanks for statistical evidence that will help me to write me upcoming new post! Hope future of peace and peace agreements will be bright and promising !