Guest Post by Megan Stewart, American University, School of International Service

Late last month, HBO announced the next project for the creators of Game of Thrones. The new series, entitled Confederate, envisions a dystopian future where the Union Army lost the American Civil War while the southern territories in rebellion succeeded. In their vision, slavery remains a modern institution. The announcement provoked anger, skepticism and concern, igniting a social media movement against the series. Those opposed to the series argued that the trappings of slavery exist today, from white nationalist terrorism and KKK rallies in Charlottesville, VA to mass incarceration and President Trump musing that President Andrew Jackson would have prevented the Civil War if he were alive, because President Jackson, a slaveholder, would have recognized that there was “no reason” for it.

With these criticisms in mind, the importance of a Union victory in the subsequent political and social development of the United States cannot be overstated. Union victory heralded the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment that permanently abolished slavery. And without a Union victory, the federal government never would have embarked upon the post-conflict rebuilding of southern states through the Reconstruction Acts and military occupation.

In a new working paper by myself and Karin E. Kitchens, we find that Reconstruction and Union occupation may have been more effective than previously understood. While some have described the Reconstruction period as “winning the war but losing the peace,” the reality is far more complex: Reconstruction did indeed achieve some of its chief policy objectives, and in some places, created a more equitable (though certainly not equal) society. Yet these very successes may have been met with violent hostility, provoked by racial resentment.

To be re-admitted to the Union after the Civil War, the southern territories in rebellion passed the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, but white southern societies created new sociopolitical institutions that re-established slavery in all but name. Some former Confederates were elected to office (including former Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens). Southern governments passed Black Codes restricting the freedoms of former slaves: freed persons were unable to bargain for a fair wage, but unemployment meant incarceration where black labor could once again be harnessed for free. White supremacist terrorist groups (like the Ku Klux Klan) attacked or murdered former slaves who became economically successful or exercised their newfound freedom. Though slavery legally ended, prior to Reconstruction, institutions remained that coerced blacks into providing cheap or free labor while circumscribing their social and economic rights.

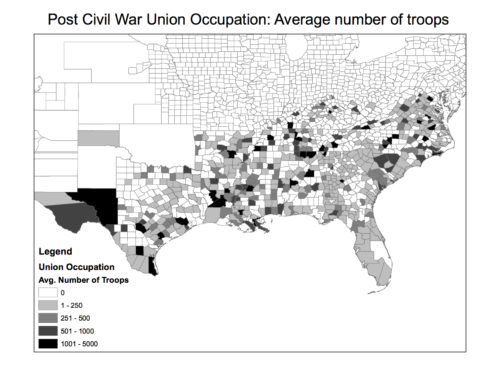

Reconstruction was a direct response to the terrorist violence, Confederate rise, and Black Codes endemic throughout the South. Congress re-deployed 20,000 soldiers throughout the south, and invested in socio-economic programming meant to rebuild southern society. The most important of these initiatives was the Freedmen’s Bureau. Though it also helped whites left destitute after the ravages of war, typically, the Freedmen’s Bureau was created to aid former slaves by providing education and health care, working with blacks to secure employment or negotiate labor contracts, and locating family members ripped apart as a result of slave sales.

In our paper, we utilize historical, geo-spatial county-level data to evaluate the effect of occupation and Reconstruction. We investigate the impact of the number of troops stationed in a county, the duration of occupation, and the presence of a Freedmen’s Bureau office in a county on black and white illiteracy rates and school attendance rates from 1870 to 1920, black and white employment status in 1900 and wages in 1940, and black and white lynchings from 1877 to 1896. What we find is that a well-resourced occupation (with a minimum of approximately 500 troops per county) or the presence of a Freedmen’s Bureau not only improved black educational and employment outcomes, but it also reduced inequities between blacks and whites living in these counties (again, but did make things equal).

We argue that the reason for the success of Reconstruction and occupation is largely due to the federal government channeling resources to communities of freed slaves. Occupied territories provided a safe space for black communities to grow and establish institutions, such as the Union League or churches, that provided educational, employment and political opportunities. Occupiers thus created a safer space for black advancement relative to areas outside occupier’s control. Likewise, the Freedmen’s Bureau directly channeled resources like education, health care and legal support into the hands of former slaves who had been legally denied these tools of social and economic advancement for centuries. In placing significant resources in the hands of freed slaves, the effects of Reconstruction endured for decades, persisting into the 1920s and in some cases 1940, nearly seventy years after Reconstruction and occupation ended.

While meeting some success in the fields of education and employment, Reconstruction failed to remedy racial resentment, as well as a willingness to use violence to maintain white supremacy and, to the greatest extent possible, an antebellum social order. What we consistently find is that the presence of a Freedmen’s Bureau office is associated with an increase in the likelihood of a (typically white) mob lynching a black man or woman, while troop size and duration of occupation failed to reduce lynchings. We believe that this relationship could be correlative—in that Freedmen’s Bureaus were located in areas with high levels of racial resentment—or causal—in that the Freedmen’s Bureau’s success in decreasing inequities between blacks and whites exacerbated white anxieties about social change to the point of murdering blacks. Some of our statistical and qualitative evidence suggests the latter may in fact be accurate. This same pattern can be found today in the racialization of, and subsequent white backlash to, contemporary welfare institutions not unlike the Freedmen’s Bureau (see here and here).

Where Reconstruction failed was in the scope of its transformative goals and the lack of resources allocated to the cause. The federal government wanted to ensure slaves were self-sufficient and not dependent on government resources, but did not seek to create racial equity, especially as Congress grew more “moderate” throughout the 1870s and southern Democrats re-gained power. Reconstruction policies did not attempt to alter the attitudes of southern (or northern) whites, accustomed to a slave culture, and many politicians (northern and southern) held racist attitudes too. Reconstruction’s failure lies here: with resources to match a vision for a racially equitable nation, the profoundly unequal society in which we continue to live may have been made a little less unjust. But to dismiss Reconstruction as wholly unsuccessful or unimportant would not be fully accurate. Ultimately, while Union victory was essential to ending slavery, it is during the years of Reconstruction that the political initiatives put forth began to make minuscule inroads in addressing the endemic injustices pervasive throughout American society.

Megan’s Stewart’s research interests lie at the nexus of state formation and civil war. Her work examines the strategic use of violence and governance during intrastate conflict, participation and civilian collaboration in civil war, and post-conflict institution building. Megan is currently working on a book manuscript, Governing for Revolution, which explores how the long-term strategic goals of insurgencies determine the inclusivity of their social service systems to both impact the war effort, as well as shape the nature of state institutions once conflict ends. Megan’s research has been published in Conflict Management and Peace Science, and is forthcoming in the Journal of Politics. For more information, www.meganastewart.org.

5 comments

Curious about your use of the term “occupation” – if one side wins a civil war and gets its own territory, how is it “occupying” it in the same way, say, Germany occupied France during WW2? Not poking/trolling, just interested in the usage. Thanks for sharing!

In the federal system up through the American Civil War, people conceived of their home state as their “country”. Federal troops would indeed have been perceived as conducting an occupation — something quite unprecedented in American history up to that time. The War actually transformed this conception of state-based citizenship, but it took decades to sink in widely.

In the federal system up through the American Civil War, people conceived of their home state as their “country”. Federal troops would indeed have been perceived as conducting an occupation — something quite unprecedented in American history up to that time. The War actually transformed this conception of state-based citizenship, but it took decades to sink in widely.

Pleased that someone applied Big Data to Reconstruction!

It is essential to do this kind of quantitative assessment to put all the opinion and commentary on Reconstruction back into context.

The root feature of racial resentment is not something that could have been legislated away. As you point out, even the “best men” were racists.

Also, there is the little matter of how Union troops actually acted (or didn’t) based on the attitudes of commanders and even individual soldiers. Not even Big Data can capture that! Back to the diaries and newspaper accounts for this dimension…

Hope you get published soon!