By Dawn Brancati.

In early June, Sudanese paramilitary forces fired live ammunition into an unarmed crowd of protesters participating in a sit-in, killing upwards of a hundred people. Previously, the government had taken a remarkably tolerant, even accommodating. approach towards the protesters, who have been demanding economic and political reforms from the government since December. In April, the military removed President Omar al-Bashar from power, and entered into negotiations with the opposition over the transition.

The crackdown has prompted many to ask what has gone wrong in Sudan? Sudan’s initial tolerance of the protests, though, is more surprising than its recent crackdown. Governments typically repress protests at a fast clip and rarely step down – willingness or unwilling – from power as a result of them. If history is any guide, the response of the Transitional Military Council is driven by the perceived threat that the protests pose to the power of military leaders and the support it has received from regional allies—rather than the diversity and nonviolent tactics of the protesters, as has been suggested.

Are accommodating, non-violent responses unique?

Historically, governments do make concessions to protesters, but these concessions do not often involve chief executives stepping down from power, as they did in Sudan. Between 1945 and 2011, governments made genuine concessions to almost 25% of democracy protests. Only 15 chief executives, though, resigned in response to 310 democracy protests in this period, while another 3 were expelled from power.

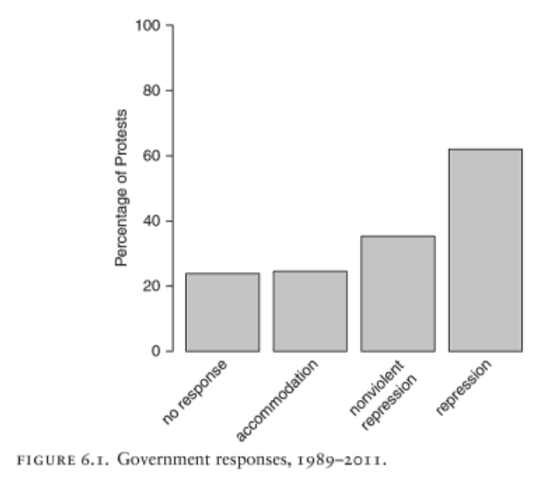

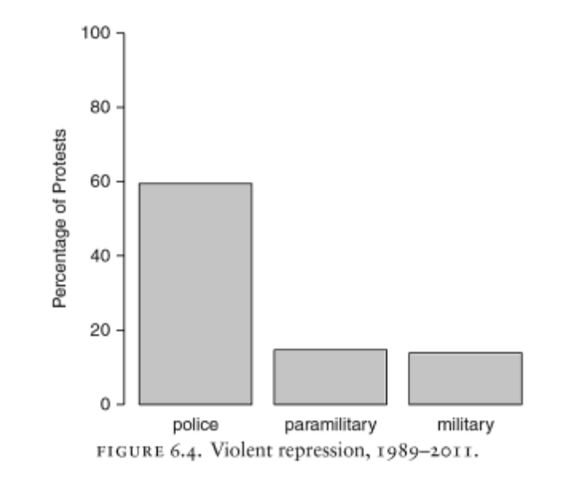

Peaceful responses to protests are much less common. Between 1945 and 2011, governments used force to repress two-thirds of democracy protests. In most cases, the police—not the military—were the ones who suppressed protesters. Militaries were generally reserved for very large protests.

Governments were also quick to use force against protesters in this period. Governments used force to repress protests an average of 12 days after the first day of demonstrations in this period. Events in Sudan deviate significantly from this general pattern. Almost 5 months elapsed before the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) tried to break up protests outside military headquarters in May, killing at least 5 people.

When Do Military’s Side with Protesters, Align with Democracy?

Militaries are critical to the success of anti-regime protests, but not much is known about why militaries side with protesters and support democratic transitions.

Much of what is known about the reasons that militaries’ ally with protesters is based on their public statements. Not surprisingly, these statements are often misleading—for instance, the Transitional Military Council in Sudan initially denied responsibility for the violence.

What is certain, though, is that militaries do not side with protesters very often. Between 1989 and 2011, militaries refused to comply with orders to repress democracy protests only 16% of the time.

Observers have hypothesized that the Sudanese protesters had heretofore been successful in extracting concessions from the government and avoiding significant repression due to their non-violent tactics and diversity in socio-economic, ethnic, and religious terms. Non-violence has been linked to protest success because it denies governments an excuse for repressing protests, and attracts supporters, who are ethically opposed to violence and fearful of being physically harmed.

Neither the non-violence of the protesters, nor their diversity. is likely to explain events in Sudan. In general, violent democracy protests are repressed more often than non-violent ones. Between 1989 and 2011, 78% of protests in which the protesters used violent tactics were repressed, whereas only 47% of democracy protests in which they did not were repressed. However, the Sudanese protesters’ tactics were nonviolent at the time of the crackdown.

Militaries are also generally more likely to sympathize and align with protesters when they belong to the same ethno-linguistic or religious group. Sudan’s military is based on conscription so that its rank-and-file is diverse. The diversity of the military’s rank-and-file is unlikely to explain the military’s tolerance until this month, and the change in its behavior. The order for the use of force came from the top leadership, while the crackdown was conducted by the RSF, which is comprised largely of former Janjaweed members.

What’s Changed?

The crackdown came after negotiations over the transition reached an impasse, and shortly after Egypt, Saud Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates renewed their support for the TMC. These negotiations reached a stalemate because the TMC has insisted on maintaining military rule until elections are held within nine months. The opposition Declaration of Freedom and Change, in contrast, has demanded that the TMC hand over the interim government to a civilian authority. The deputy chief of the TMC, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, is widely believed to be eyeing the presidency, which early elections would make more likely.

What’s Next?

The future of Sudan is likely to look much more like Egypt than Syria. The Egyptian Revolution was cut off at the knees in 2013, when the Egyptian military ousted the democratically-elected Mohammed Morsi from power, reportedly with the support of the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. The 2011 protests in Syria, in contrast, devolved into a civil war when the ranks of the military split, with certain factions lining up against the Assad regime.

If Sudan’s security forces fragment and the military allies with the protesters, then another Syria is possible. Tensions between the military and the RSF do exist. Factions of the army are said to be dismayed with how the RSF’s use of violence has tarnished it image, and resentful over the advantages that the RSF enjoyed under the al-Bashir regime. However, at present, this does not seem the most likely outcome.

Egypt, and Saudi Arabia and UAE have pledged political and economic support for the Sudanese government. Sudan has strong ties with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, in part due to its support for their involvement in the civil war in Yemen. And, so far, foreign allies have not offered military or economic aid to the opposition. The African Union has suspended Sudan from the organization until a civilian government has been restored but has not offered forces to defend the protesters.