Ethnic groups are not states. This simple fact seems to elude many journalists and, on occasion, scholars. But my aim in this post are journalists and in particular the June 5, 2012 New York Times story about the controversy over the Askariya Shrine in Samarra, Iraq, “Violence Spreads in Struggle for Shrine” by Tim Arango and Yasir Ghazi. In the story, the reporters depict the conflict as “a dispute escalat[ing] between Sunnis and Shiites.” It discusses Sunnis and Shiites as if they are distinct, bounded, groups fighting one another because of past grievances. The journalists don’t question this “groupist” position in their own reporting. They do, however, offer two quotations from Iraqis that directly contradict the groupist ontological understanding of ethnicity. One Iraqi asks, “what did the victims of today do to be killed? Sectarianism has no mercy against anyone, and there are groups of criminals and militias used by officials and politicians to achieve their specific agenda.” Another says, “They are not fighting for the shrines; they are fighting for the money that these shrines can bring to them. It’s just another way to play with people’s emotions to gain advantage.” Both of these quotations offer a Rogers Brubaker-type approach to understanding ethnicity and conflict: conflict is waged between leaders and their organizations who manipulate ethnic identity for narrow gain. Violent conflict does not occur between bounded, whole, discrete ethnic groups for the very reason that ethnic groups are not bounded, discrete wholes. Ethnic “groups” are messy, dissimilar units. They are not like states because they don’t have features such as clear, internationally-demarcated borders or legitimate domestic legal systems. Members of different ethnic categories blend together, cross borders, and interests can be extremely heterogeneous. Some ethnic groups have clearer boundaries than others. Ethnic groups do not fight one another in similar ways that states do, because ethnic groups are not like states. We err when we treat ethnic groups as distinct wholes—scholars and journalists alike have much to learn from those Iraqis quoted in the article.

You May Also Like

MBS Doesn’t Care About Human Rights. He Does Care About Google.

- October 22, 2018

Guest post by Corey Ray and Sofia Smith. The disappearance and assumed murder of activist Jamal Khashoggi by the…

Will the Afghan Peace Talks Succeed?

- September 18, 2020

By Aila M. Matanock Last Saturday saw Afghan factions come together in Doha for peace talks. The Taliban,…

Why No One Wants to Call Syria a Civil War

- June 11, 2012

By Barbara F. Walter and Elizabeth Martin Syria has been in the midst of a civil war since…

What Electoral Reform Means for Iraq

- January 14, 2020

Guest post by Ariel I. Ahram The dramatic escalation of US-Iranian tensions affects no country more than Iraq.…

Israel, Iran, and the Holocaust Analogy

- July 10, 2012

By Andrew Kydd As the negotiations over the Iranian nuclear program grind to a halt, we are likely…

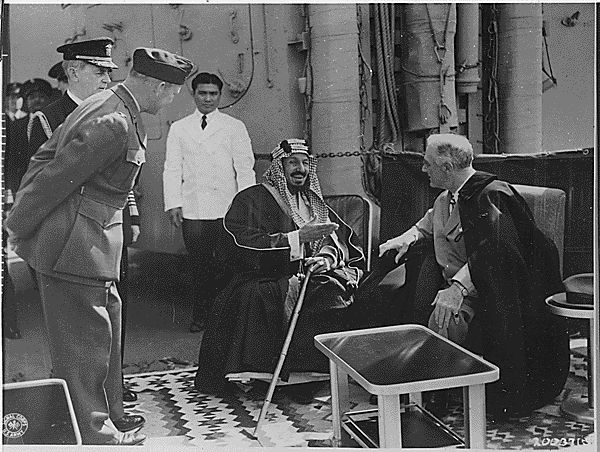

Friday Puzzler: Why No Coups in Saudi Arabia?

- July 31, 2015

By Barbara F. Walter I had the pleasure of having lunch in D.C. on Wednesday with a bunch of extremely…