Guest post by Brian Forst.

Not sure whether it qualifies as terrorism? Call it “terrorish”

Academics do not agree on the definition of terrorism. Nor do policy makers. Federal agencies use different definitions too, as do the member states of the United Nations. Problems in defining terrorism has been a recurring theme at Political Violence @ a Glance as well.

This is quite unlike a more common form of aggression – crime – which is defined in the criminal code, enacted by legislatures. If an act violates that code, it is unambiguously a crime. Terrorism is a federal crime, but the federal criminal code sheds little light on the larger question: precisely what is terrorism?

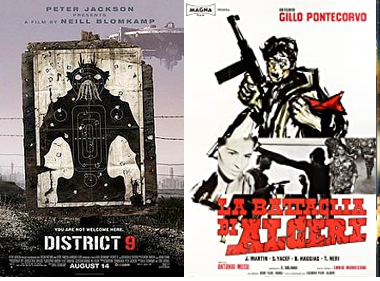

In one session of a class I teach on terrorism each year, the students discuss, and sometimes argue fervently over, what precisely is meant by “terrorism.” Most subscribe to a standard textbook definition, that it involves violence committed to achieve a political aim, usually to instill fear in a target population. But beyond that there is substantial disagreement. Do threats alone to commit violence qualify as terrorism? What about attacks on purely symbolic targets, such as statues of the Buddha or treasured antiquities? What about hate crimes? Is the Ku Klux Klan a terrorist group?

Political debates over terrorism only compound the problem. Right-wing politicians express great concern over acts of violence in the name of Islam – “Radical Islamic terrorism” – rarely mentioning any other act that satisfies most definitions of terrorism. Politicians on the left typically regard acts of violence by hate groups as equally worthy of counter-terrorism interventions, noting a sharp increase in such events in recent years, while jihadist terrorist events committed on US soil have remained fairly stable since 9/11.

This debate is likely to become more heated and consequential as the number of right-wing incidents of violent extremism continues to grow, as is likely in an increasingly polarized and toxic political climate, with dog-whistle exhortations to violence from high places becoming all too common. The debate is not just ideological; it has implications for counterterrorism policy. If these are not regarded as terrorist events, the burden of resolving them will fall more heavily on the shoulders of state and local law enforcement authorities, with less help from federal agencies. This could clarify responsibilities, but having more enforcement and prosecution options readily available is likely to make the responses more effective.

What do we call these acts that satisfy some, but not all, of the essential elements of the most widely used definitions of terrorism? How do we classify them? One solution would be to coin a new general category – perhaps “terrorish” or “terroresque.” If you don’t like my definition of terrorism, you can call an act that falls under my definition, “terrorish”; I can do the same if I disagree with yours. This might not enlighten counterterrorism policy, but it could lighten up the political and media discourse a bit.

Over the longer term, we should be able to find more acceptable solutions to the current muddle. Scholars can aim to achieve a consensus on definitions to advance our understanding of terrorism over time and place. The nature and form of terrorism have changed over the years; both are likely to keep changing as technology and the political landscape continue to change. How do we know if strategies or interventions work if the target keeps shifting? One solution would be to distinguish different categories of terrorism and political violence – a morphology of terrorism – and track changes by category. Lone-wolf versus two-person versus three-or-more person terrorism is one basic dimension for distinction. Violence committed in the name of Islam versus all other is another, as are right-wing and hate crime acts against ethnic groups, LGBT, and other targeted minorities. Trends both within and between these various categories could go a long way to help sharpen our understanding of terrorism.

For the purposes of counterterrorism policy, we would do well to embrace the absence of a one-size-fits-all definition of terrorism. Why not recognize the distinct advantages of having multiple definitions? For academics who study terrorism, there are advantages in testing the implications of any set of findings under alternative definitions of terrorism, to see how the choice to use any particular definition of terrorism can alter the findings for different types of settings and problems. We have only scratched the surface in doing this kind of research.

For agencies responsible for counterterrorism, there are also advantages in having multiple definitions. Different agencies have different missions; they cannot all be responsible for each and every type of terrorism in all places. If terrorism were to be defined down to a single cookie-cutter definition for all agencies responsible for counterterrorism – possibly as Daniel Patrick Moynihan once argued that deviancy had been defined down, to the public detriment – we would lose the advantages of economies of specialization and division of labor, and the terrorists would be the beneficiaries, exploiting the cracks in any particular definition.

When it comes to defining terrorism, we might best follow the general advice of Chairman Mao: Let hundreds of flowers bloom.

Brian Forst is Professor of Justice, Law and Criminology at the American University’s School of Public Affairs. He wishes to thank Joseph Young for helpful suggestions on a draft of this essay.