By Emily Hencken Ritter and Christian Davenport. Art by Sequential Potential.

On January 6, 2020, a pro-Trump mob stormed the Capitol building in Washington, DC, halting the count of electoral votes to confirm Joe Biden’s presidency. This happened as the House and Senate debated a move by a faction of Republicans to overturn the election results. Protesters violently entered the congressional building; property was damaged, people were injured, and five people died in the process. In addition to the temporary occupation of the Capitol building, incendiary devices were placed at the Republican and Democratic Party headquarters.

In media coverage and public discussions of these events, there has been considerable debate about what the event was. A protest? Dissent? A riot? Insurrection? Terror? A coup? Or was it some sort of hybrid that has yet to be labeled?

Language and concepts matter. They help us understand why something happened, because we can compare it to other instances of the same thing. They tell us what to expect in the next stage, based on similar events. They establish equal treatment, if applied to equal situations. They unite and divide. They also reveal when discussions become improper or even ridiculous.

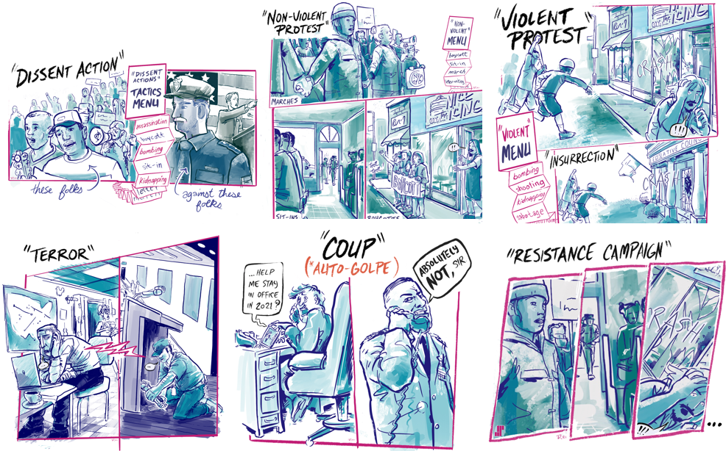

With this in mind, we provide some definitions of various types of political violence, which represent a consensus of how political conflict and violence scholars define these terms. We also provide visualizations, which help communicate what words intend, but can never quite capture alone.

To be clear, what we list and define here are tactics. They are not classes of people, nor are they distinct classes of politics. They are what Charles Tilly would call a “repertoire” or what Joseph Young and Stephen Shellman call “menu” items: tactics of contention that people choose from when competing with the state for resources, policies, and status.

A Glossary of Political Violence

Dissent or Protest: a coordinated attempt by nonstate actors to influence political outcomes that is not organized by the state

Dissent and protest are any actions people take together—whether organized or not—that threaten those in power with negative consequences to achieve a political outcome, whether a change in regime, secession from the government, a policy or practice of social justice, or attainment of more resources or benefits for their group. Dissent and protest are part of the process of contention whereby the agents of change square off against the agents of the status quo—in government, corporate boardrooms, or wealthy neighborhoods. (Status quo on the part of the state is alternatively labeled state repression, human rights violation, protest policing, riot control, public order management, counter-terrorism, counter-revolution, or counter-insurgency.)

Protest and dissent are umbrella terms that include many different tactics, which may be violent or nonviolent. One of the more complete listings of dissent and protest activities can be found here as compiled by the Dynamics of Collective Action project. Tactics on the menu include:

- Rally or demonstration: Gatherings of people who come together to hear speeches, preaching, or singing in support of a cause

- March: Movement from one location to another while chanting or displaying signs

- Picket: Holding signs while standing in a line or walking in a circle in support of a demand

- Symbolic display: Art, signs, installations, actions that have symbolic meaning, such as graffiti, performance art, holding crosses, or burning flags

Many dissent/protest actions occurred in the events at the Capitol on January 6. President Trump held a rally to speak in support of action against the congressional vote; individuals in the crowd marched from one location to the Capitol building where they engaged in a demonstration; while there, they held signs and symbols that had meaning to them such as confederate flags; some of them went on to use violence against police and property; some moved into the Capitol building itself to occupy it.

These “menu items” are precise descriptions of behaviors. In contrast, words like “insurrection” or “terror” describe much more: they connote feeling, intent, and threat as well as aftereffects.

One way to categorize protest and dissent is whether the action is violent or not.

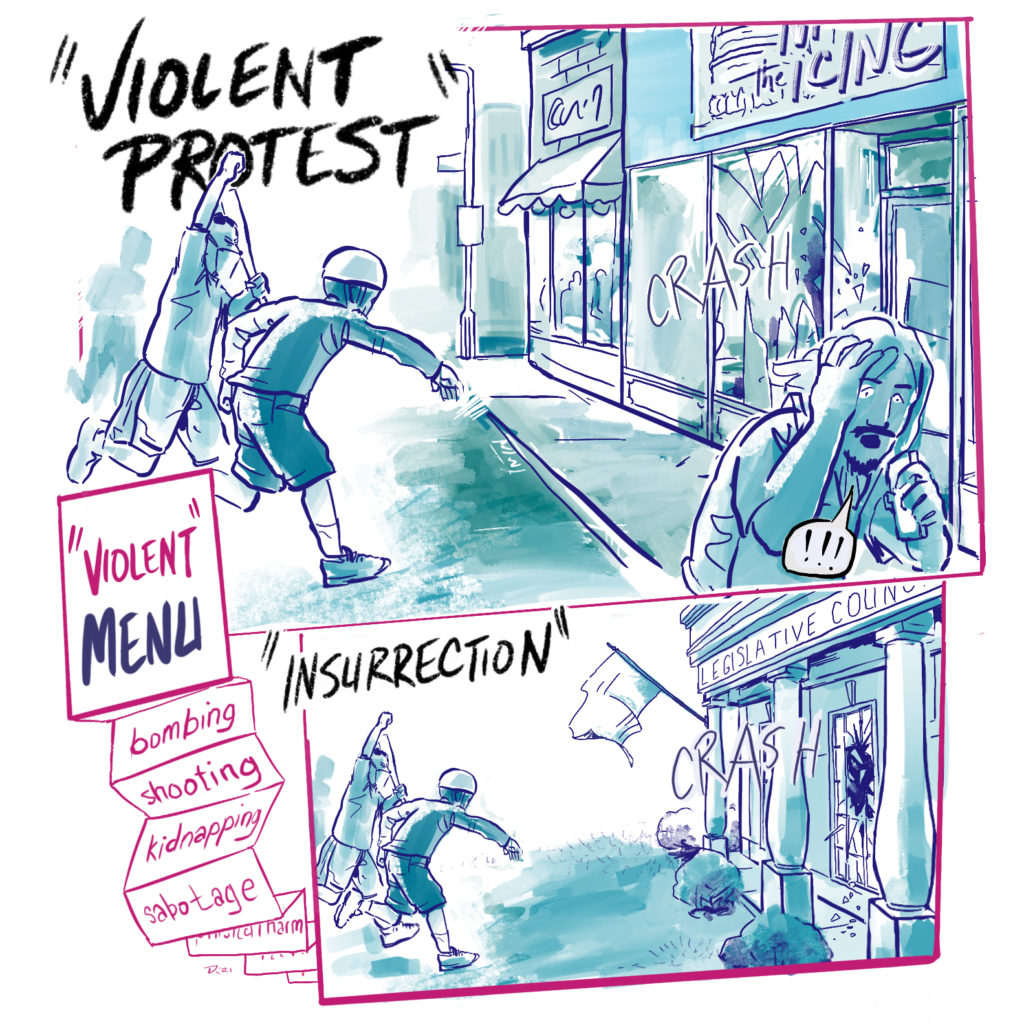

Non-violent protest: a public action to coerce or apply some form of power against powerholders without the use of violence.

Violent protest: a public action to coerce or apply power against powerholders with the use of violence.

Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan write that “Violent tactics include bombings, shootings, kidnappings, physical sabotage…and other types of physical harm of people and property.” Riots or “mob violence” take this further, representing a large group of perhaps 50 or more people that damages property or persons, usually over the course of several hours and perhaps even days or weeks. Notably, participants having weapons does not make them violent—there must be damage or injury (which does not always require a weapon).

We tend to use insurgency or insurrection when referring to violent protest, and this is appropriate for the DC events. The key is that the actions are violent, and the target is a government.

Insurgency, insurrection, or uprising: violent acts of resistance against a sitting government.

Now, let’s turn to a word that has commonly been used for the violent actions in DC:

Terror: a conspiratorial practice of calculated, demonstrative, direct violent action without legal or moral restraints, targeting mainly civilians and non-combatants, performed for its propagandistic and psychological effects on various audiences

If the protesters had intended for the dissident actions to be non-violent—a rally and a march, perhaps—but then spontaneously became violent after frenzied speeches and actions, we would not consider this an act of terror.

But the events of January 6 were much more than that. The pipe bombs planted at the RNC and DNC headquarters suggest strategy and planning, and thus have more of an air of terror about them than the storming of the Capitol. And more evidence has come to light about the advance planning for violence: people openly discussed plans to break into the building and attack or “arrest” members of Congress and brought supplies for the express purpose of damage or injury.

In other words, there was a calculated plan to use violent action against civilian targets to make a psychological and propagandist point to public audiences. This is an act of domestic terror.

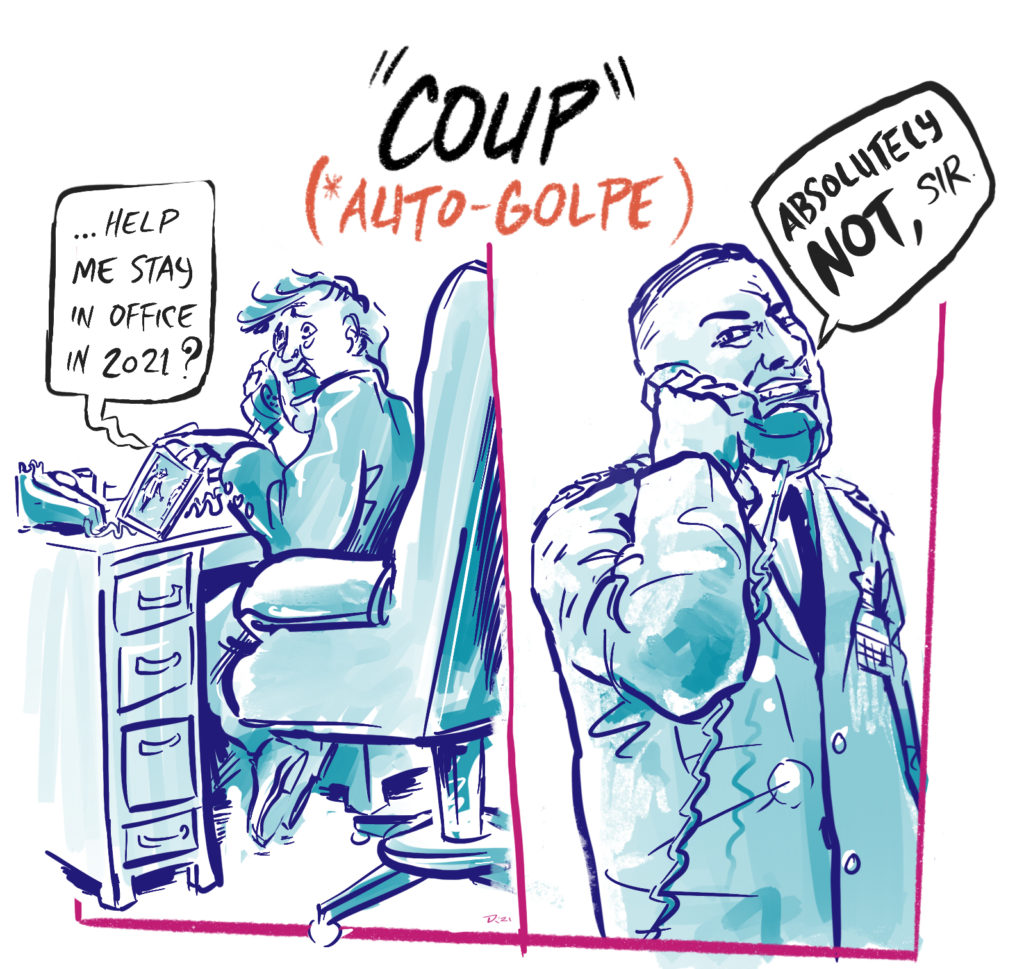

Pundits have frequently used the term “coup” to refer to President Trump’s assertions of election fraud. But neither Trump’s words nor deeds constitute a coup. A coup requires an extremely powerful group to support the executive (or their replacement), and that group is almost always a military. This is certainly not a descriptor for his supporters.

Coup: a coup attempt involves an illegal, overt effort by civilian or military elites to remove a sitting executive from power.

Autogolpe: what scholars call an attempt at a “self-coup”—or, using the Spanish term, an autogolpe—in which a head of state attempts to remain in power past his or her term in office.

Instead of a coup, we might call last week’s actions the start of a popular rebellion.

Rebellion or revolution: the political response of a deprived group or class aimed at transforming existing political, economic, and/or socio-cultural relations, practices, or outcomes.

Examples of rebellions include the activity of peasants in Central and Latin America, poor people in Appalachia at different historical moments, the 2011 Arab Spring, and the American, French, and Haitian revolutions.

If the events on January 6 were intended to overthrow the government, we would be more willing to classify the actions as a rebellion. Because the protesters were mostly dissenting against election outcomes, the events in DC do not quite qualify. (We recognize that many of the participants may indeed want to overthrow the government or shift societal power toward an ethnic group, but that was not the aim of the actions.)

The WAVELENGTH of Violence

There were many tactics used at the Capitol, emerging in an escalating sequence. While the events began with a non-violent assembly and march, the actions became violent when dissenters pushed past and threatened law enforcement, damaged items in the Capitol and the building itself, and attacked police and security guards. What this shows is that one form of contention (nonviolent protest) can easily turn into another (a violent riot).

Some scholars like Clark McPhail argue that the DC events should be understood, not as a single event, but as many different events. Some rushed the Capitol building to vandalize and occupy; others stood outside and took selfies; others stayed within eyesight of events but did not directly take part in them. Will Moore emphasized the dynamic back and forth among different actions/tactics, showing that dissidents and their opponents react to one another—sometimes escalating, sometimes de-escalating.

Reality is messy, and often involves combinations of tactics, like assembly-march-standoff-occupation. It is better to embrace the complexity of truth than the inaccuracy of convenience.

A useful term we have not seen, either in the media or in academic discussions, is campaign.

Resistance campaign: “A series of observable, continual tactics in pursuit of a political objective”.

The rally, march, and assault were a culmination of prior events that are part of the same movement that includes disinformation campaigns and protests in cities across the US. Knowing that the events of January 6 were a moment in a campaign suggests that it is unlikely to be finished altogether.

Just Semantics?

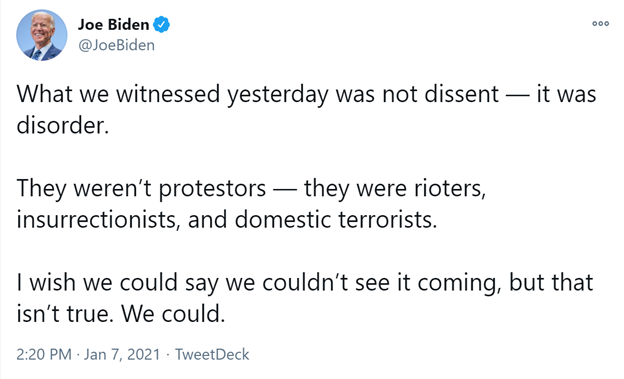

Is this all just semantics? We don’t think so. The words we use to describe an event ultimately determines how we respond to it. Consider President-elect Biden’s tweet the day after the violence at the Capitol:

“Dissent” and “protesters” are words that accurately describe the events and the participants. But Biden wanted to do more than just describe. He wanted to proscribe (delimit) and prescribe (put forth actions to deal with the issue) as well.

By calling the participants of the events in Washington rioters, insurrectionists, and domestic terrorists, President-elect Biden—and many others—have decided that what occurred in Washington was horrific and illegal and should be opposed with arrests and perhaps more.

Words aren’t just words. They are political. And, as Will H. Moore wrote, “[w]hen we use the words employed by politicos as concepts in our theories, we engage in a political act, regardless of whether we intend it as such or recognize that we do so.” Scholars, journalists, and the public would therefore do well to use their words carefully—knowing that in politics, they may be matched with consequences.

The illustrations in this article were created by Sequential Potential