Guest post by Josh Meuth Alldredge, Rafael Ch, Angelika Rettberg, María Paula Rojas, and Michael Weintraub.

Although the current demobilization with the FARC represents an important advance for territorial security in Colombia, with concrete gains for a variety of security indicators, the peace process has occasioned new forms of violence. Perhaps the most visible and disconcerting development on this front has been the systematic targeting of social leaders (human rights activists, environmental activists, and labor unionists, among others). While the assassination of social leaders is a phenomenon observed before the FARC’s demobilization, the last 15 months has experienced a dramatic increase in killings, reaching more than 150. In addition to the selective assassination of these visible defenders of individual and community rights, security challenges in the future include the construction of responsive, accountable state institutions – particularly in areas where the FARC were once dominant – which could help mediate disputes, regulate property rights, and perform other justice sector functions. Finally, illicit economies continue to thrive despite the conclusion of the peace agreement with the FARC, including but not limited to the cultivation, transshipment, and sale of coca, as well as illegal mining.

Given this challenging context, the Data4Peace Territorial Security team posed a set of questions, two of which we discuss in this post. First, why have social leaders become targets for social violence? If it is possible to identify the risk factors for future attacks, it might be possible to prioritize vulnerable municipalities where state authorities could concentrate their efforts to deter such attacks. Second, we asked whether the legacy of political mobilization of the leftist Patriotic Union (a party tightly linked to the FARC that was systematically eliminated in the 1980s) persists up to today. The logic here is that understanding whether areas where guerrilla groups helped to organize themselves legally are different today from those where that party was not active; furthermore, this might help inform policymakers about the medium to long-term future of areas where the FARC will be politically mobilizing its potential constituents.

Using tools of statistical analysis (multivariate regression) and a dataset spanning decades, the team generated the following preliminary conclusions.

Assassinations of Social Leaders

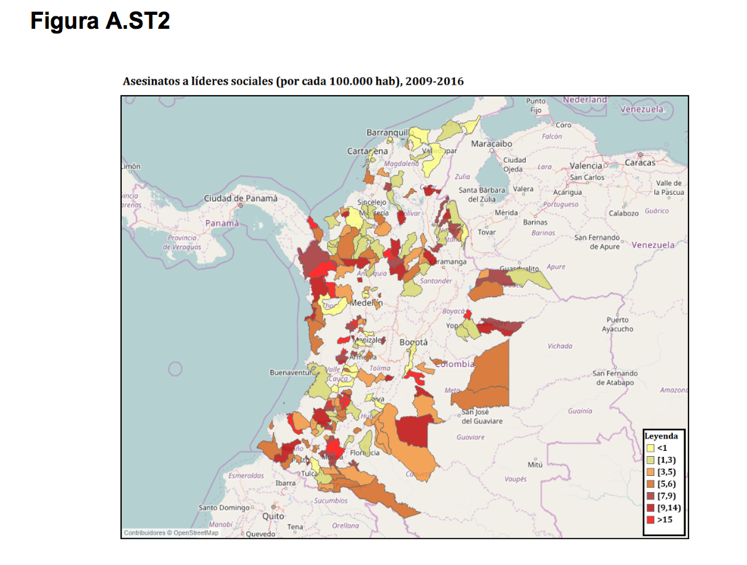

We began by establishing the geographic reach of killings of social leaders, using data from Somos Defensores. As the map below indicates, there are areas that concentrate a large number of killings, such as Chocó, Antioquia, the border regions of Putumayo, and Norte de Santander. Moving beyond mere description of where these killings have occurred, we generated a set of hypotheses that we then brought to the data. All the results reported below control for a set of variables that might confound the relationship between our variables of interest and the killing of social leaders, including municipal geographic characteristics, previous armed group violence, cocaine and extractive industry production, among others.

Figure 1. Killings of Social Leaders Per Capita, 2009-2016

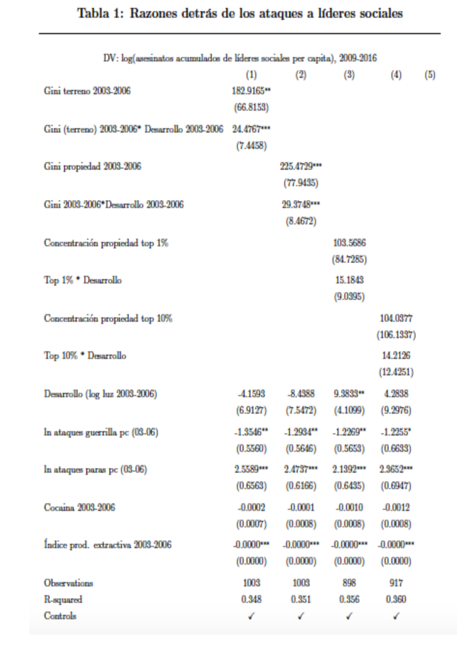

Economic factors: Our results show that relatively rich municipalities with high concentrations of land (more inequality) are witness to more attacks per capita against social leaders, while poorer and more equal municipalities show significantly fewer incidents of violence against prominent social actors. In other words, killings of social leaders are most likely to happen when (1) there is a demand for redistribution given present inequality, and (2) where the stakes are high for status quo actors, i.e. there is something valuable to potentially redistribute. Somewhat surprisingly, we also found that coca cultivation has a negative impact on social leader killings, which may suggest that the presence of large-scale operations by armed groups to oversee coca cultivation actually provides relative security for social leaders.

Military factors: Social leader assassinations appear to be related to histories of violence. Where FARC expended significant effort in controlling territory (measured by clashes), social leaders were killed at a significantly lower rate when compared to municipalities that were contested extensively by right-wing paramilitary groups.

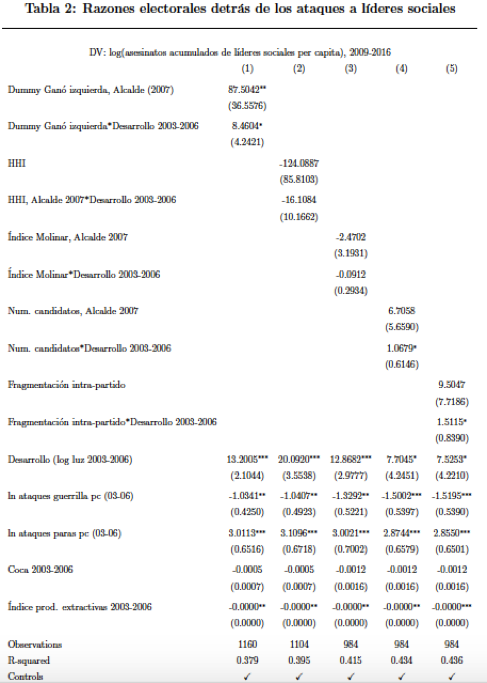

Results from Ordinary Least Square (OLS) Models of Killings of Social Leaders

Legacies of Left-Wing Political Mobilization by Insurgents

To examine the possible legacies of the political mobilization of the FARC, the Territorial Security team reviewed election data from the mid-to-late 1980s, when the Patriotic Union was formed. Through the use of multiple tests and statistical specifications, we found that these election results did not have a significant lasting linkage with either contemporary state presence or contemporary attitudes toward the FARC peace deal. This suggests that state authorities may have little to fear about the long-term consequences of FARC’s political mobilization efforts.

The findings above yield several recommendations for Colombian policymakers. First, to protect social leaders, we recommend that rich, unequal municipalities are prioritized for the protection of social leaders. Additionally, we suggest that municipalities with close recent elections (and those with recent leftist party winners) are carefully monitored for the possibility of violence. It is essential that the Colombian state work to neutralize interests that would be served by the assassination of social leaders.

Second, we recommend that community institutions built or supported by the FARC in the past be integrated into state plans for institutional development, and that judicial institutions are strengthened in communities with heightened risks for violence.

Finally, we suggest that the Colombian state be open to piloting new territorial security programs, rather than rolling out nationwide programs, and that monitoring and evaluation methods be incorporated into all efforts to bolster territorial security.

1 comment