By Michael Kalin & Nazita Lajevardi for Denver Dialogues.

On the eve of Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration, many Muslim Americans have reason to fear.

Between the time he waded into the fray of the Republican primaries and his electoral victory last November, the President-elect has promised and prevaricated about banning Muslim immigration, building a registry to track Muslims in the United States, and increasing surveillance of Muslim communities across the country. It remains an open question as to whether and how he will translate these ideas into actual policy. Still, Trump and his supporters cling to the notion that a culture of political correctness has prevented the Obama administration’s Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) strategy from confronting the threat posed by radical Islam.

Yet, if the example of the New York City Police Department’s spying on local Muslims is any indication, the real-world practice of counter-radicalization has often done too little to distinguish radical Islam from the daily practice of millions of faithful Americans who live ordinary and unremarkable lives. The NYPD’s own published work on the matter makes this abundantly clear. It points to common markers of Islamic religiosity—wearing traditional Islamic clothing, growing a beard, becoming involved in social activism and community issues, giving up drinking and smoking—as “typical signatures” of latent Islamic extremism.

This conflation of common piety with radicalization has had real and grave consequences for the Muslim American community. A 2013 qualitative study of the effects of the spy program noted a broad “chilling effect” on community mobilization around Muslim civil rights issues and political activism more generally.

Given the heated rhetoric during the last election about the association between Islam and radicalization, could something like this ‘chilling effect’ be operative among members of the community today? Answering this question is much more difficult than it sounds.

First, it is nearly impossible to gain a representative sample of Muslims in America because the US Census does not collect data on religious background. That’s one reason the estimates we have on the number of Muslims ranges so widely, from 2 million – 12 million by some accounts. From the perspective of anyone conducting a survey, the problem is compounded by how heightened distress may decrease response rates and bias answers. This question is no longer theoretical. Last fall, Muslims across the country feared they were being surveilled—rather than merely surveyed—when asked to indicate their religion on an automated telephone poll conducted by a non-profit organization ironically seeking to empower them.

In an effort to better understand this anxiety, we rely on a recent survey of a panel of 200 Muslim Americans conducted in December 2016 through Survey Sampling International. As samples go, we stress that this one has serious limitations. At the very least, it is likely overrepresented by younger Muslims who are open to discussing sensitive questions. Still, the data reveals important patterns, especially after taking into account the difficulties in reaching a vulnerable but critical population about whom we know so little.

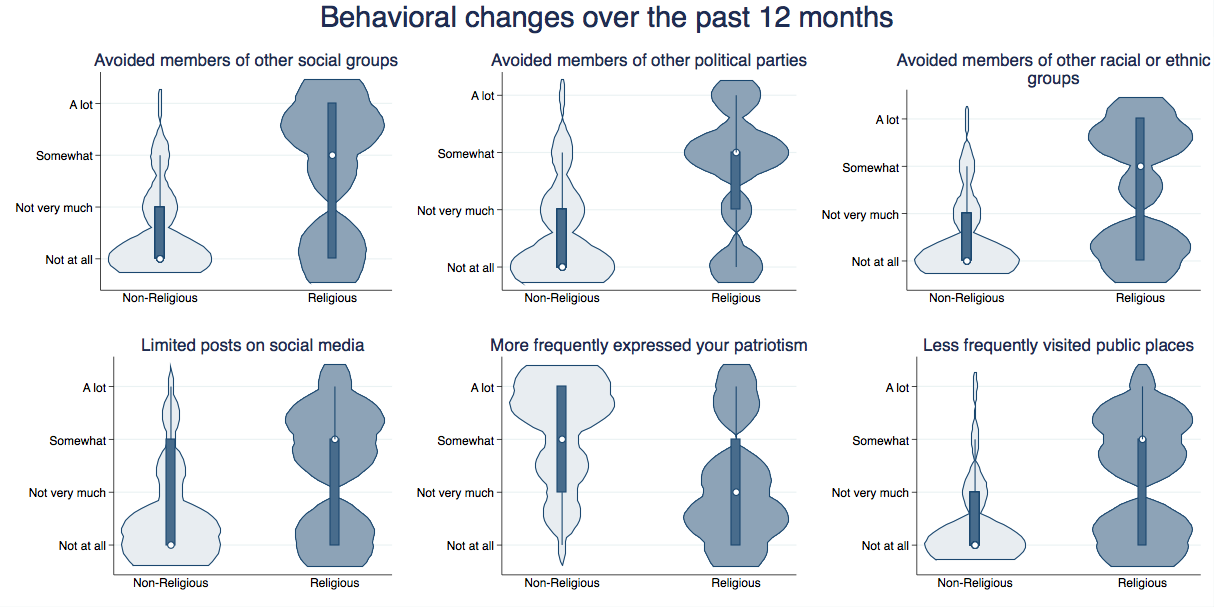

In this sample, we find that religious Muslim Americans—defined as attending mosque at least once a week—were significantly more likely than their secular counterparts to report increased avoidance behaviors over the past 12 months. Relative to the previous year, these religious respondents reported avoidance of public places, as well as avoiding mixing with members of outside social, racial, and political groups. They were also significantly more likely than non-religious Muslims to have engaged in self-censorship online. In the figure below, we compare behavioral changes over the last year reported by religious and non-religious Muslim respondents in a series of violin plots:

Figure 1 (*please click image to enlarge)

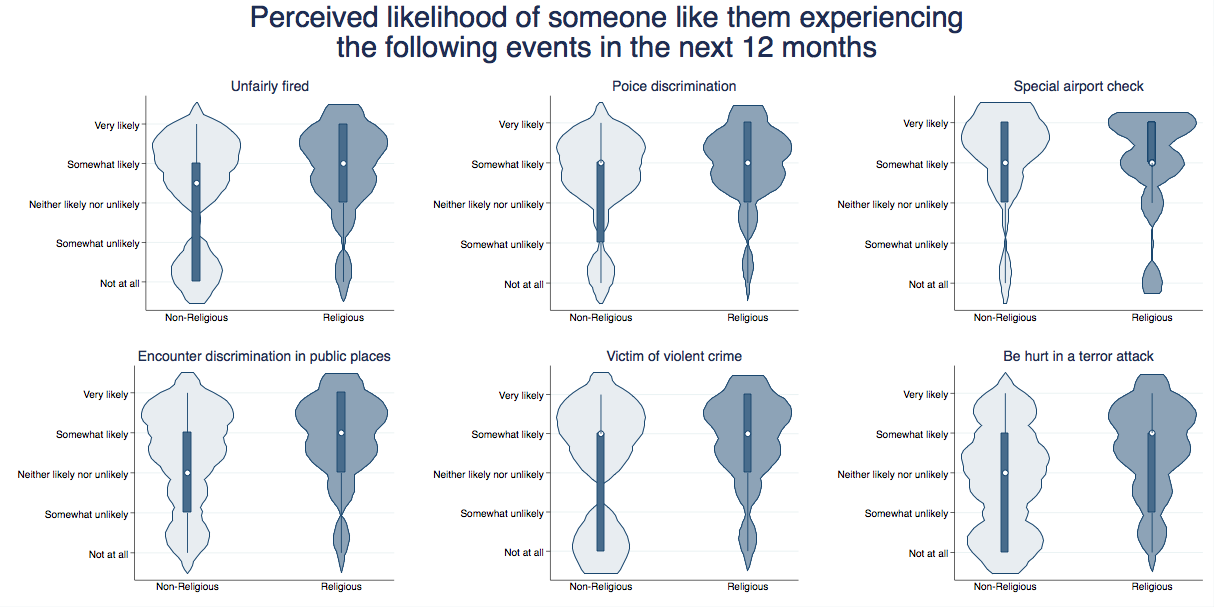

Nor is it just retrospective. When asked to consider the next 12 months, religious Muslims were more likely than their secular counterparts to believe that they, or someone like them, would be unfairly fired, would encounter discrimination at the hands of law enforcement or in public places, and would more likely be a victim of both a terror attack and violent crime.

Figure 2

Of course, these findings are based on observational data, which means we cannot conclusively demonstrate that the current political discourse is causing our respondents to feel this way. Still, they are strongly suggestive of a heightened level of fear within the Muslim American community, along with observable signs that religious Muslims are increasingly taking refuge from society at large.

“Islam,” Trump once intoned, “hates us.” Such sentiments impugn the faith of millions of patriotic citizens. Today, Muslim Americans live in a country where the basic signs of their identity, religious practice, and communal life are explicitly designated as not only suspect but, in the eyes of many, as something fundamentally alien and hostile. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that this kind of rhetoric has had toxic effects on their civic engagement in our democracy, rendering Muslim Americans among the most marginalized groups in America today. We know little about what the incoming administration has in store for them. What we do know is that the current climate has made it all the more challenging for an isolated and vulnerable minority to defend its constitutional rights and all the more necessary for a broad and concerted coalition to stand with it in solidarity.

Michael Kalin is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Sié-Chéou Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver. Nazita Lajevardi, a PhD Candidate at UCSD and an attorney by trade, is scholar of race and ethnic politics, with a specialization on Muslim Americans.