Guest post by Erin M. Kearns.

In an interview this week, President Trump stated that high level intelligence officers told him that torture absolutely works. This directly contradicts expert opinion. The 2014 Senate Torture Report shows that torture did not elicit actionable intelligence. Secretary of Defense, James Mattis, opposes torture in favor of rapport-building interrogation practices. Trump’s statement also contradicts a body of academic research. Despite widespread evidence against torture, why do people still support it?

In a recent Duck of Minerva post, Amanda Murdie articulated a “not-so-fictional” discussion familiar to most of us who study torture and security issues more broadly. The research overwhelmingly says that torture doesn’t work. Many intelligence officers argue against torture in favor of rapport-building techniques. Yet vast swaths of the general public remain convinced that torture is appropriate in the context of counterterrorism.

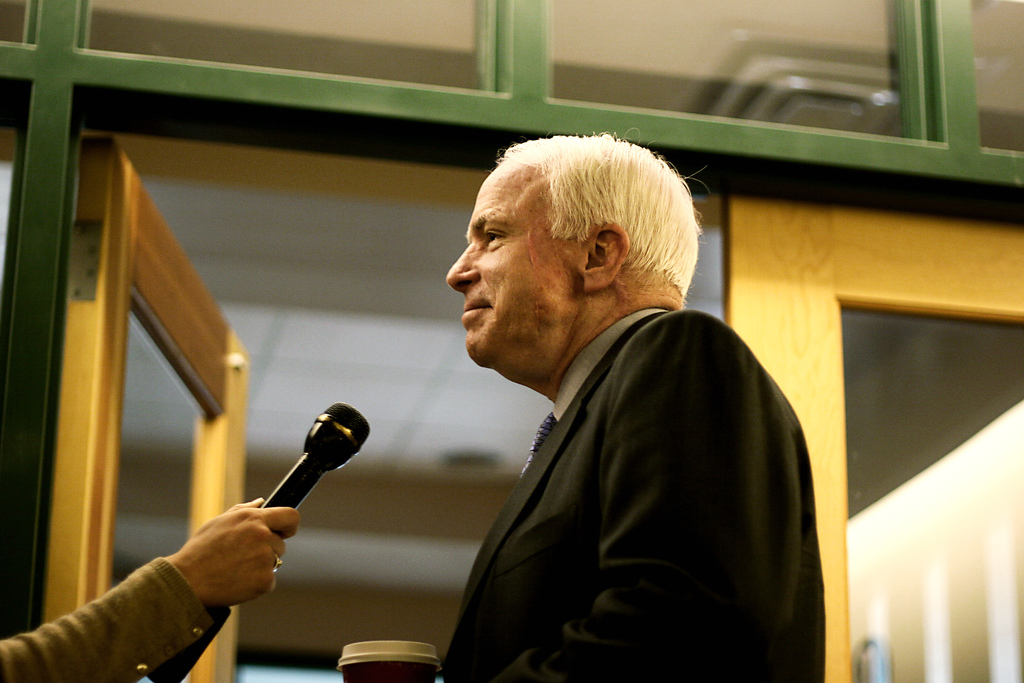

We have debated the use of torture in interrogations – particularly with terrorism suspects – for over a decade. Vocal opponents ranging from Amnesty International to Senator John McCain have repeatedly condemned the practice. At the same time, media have increasingly depicted torture as an effective strategy to elicit information. According to the Parents Television Council, entertainment media depictions of torture rose from 110 scenes between 1995 to 2001 to over 600 between 2002 and 2005. With conflicting information about torture, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that public opinion on it is still split.

According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, 48% of the public thinks that there are some situations in which torture is acceptable in counterterrorism. Public opinion polls on torture, however, frequently ask about support in the abstract without examining other factors that may impact perceptions – yet, framing matters. For example, in November, President Trump appeared to moderate his opinion of torture after speaking with General Mattis but has since returned to supporting the practice. This wavering view on torture is quite common. In short, support for torture is not fixed. Fortunate for us, this means that people’s opinions can be changed.

Experimental research shows that people are more likely to support torture when it is used against a member of an out-group (here and here), involves psychological versus physical harm (here), or happens further from home (here). Beyond framing, the body of academic research highlights a number of the problems of torture in counterterrorism – it provides misinformation, not actionable intelligence; it is not legal; and it does long-term harm to all involved. Rather than protecting us against future violence, using torture may actually leave us more vulnerable to terrorism.

Beyond the legal and ethical considerations, experts generally agree that torture is ineffective. Yet, findings from academic research on torture are not easily transferable to public knowledge. For most Americans, torture is an abstract concept where their only exposure is through television and movies. This limited perspective on torture can explain why some people support it.

My own research with Joseph K. Young tested the impact of media framing on support for torture. We found that people who view a clip from the television series 24 in which torture works are more likely to both say that they support torture and sign a petition in favor of using torture in terrorism interrogations. Contrary to expectation, viewing a clip where torture was ineffective had no impact.

Media depictions of torture tend to grossly exaggerate the benefits and minimize the costs. In media, torture almost always is used against an out-group member and the results are positive – information is gathered, an attack is thwarted, and everyone is safe. On 24, Jack Bauer does not display psychological or physical damage from his role as a regular torturer. Most informed observers know that this narrative is fiction, but the public may not.

To move the needle on public opinion, we need to change the narrative. As my work suggests, this does not mean that we could merely show torture as ineffective at gathering information. Rather, academics and practitioners should make our work more accessible to the public in an effort to inform and impact perception. Murdie, for example, does an excellent job at summarizing dense academic work that is often inaccessible to the public – both through lack of access and lack of training – and making it digestible. Further, this can be done through narrative accounts of torture’s impact on victims and perpetrators alike, demonstrations of its lack of efficacy, and pushing beyond the usual trope of white savior and Muslim perpetrator in media depictions.

Erin M. Kearns is a postdoctoral research fellow with the Transcultural Conflict and Violence Initiative in the Global Studies Institute at Georgia State University.