- Art is used to promote war. Monarchs, dictators, and elected world leaders have all commissioned artists to create propaganda to generate popular support for wars and to urge the public to make material sacrifices needed to sustain wars.

In their work, these artists have depicted the opposing side as aggressive, powerful, and savage in order to stimulate animosity and fear for the opposing side. To evoke a sense of nationalism and pride among compatriots, they have depicted battlefield victories, and to stress the need for continued support, they have portrayed the toll of war on soldiers and citizens.

Although, in general, propaganda art is not technically strong or stylistically innovative, some well-known artists, such as Norman Rockwell, have produced wartime art propaganda.

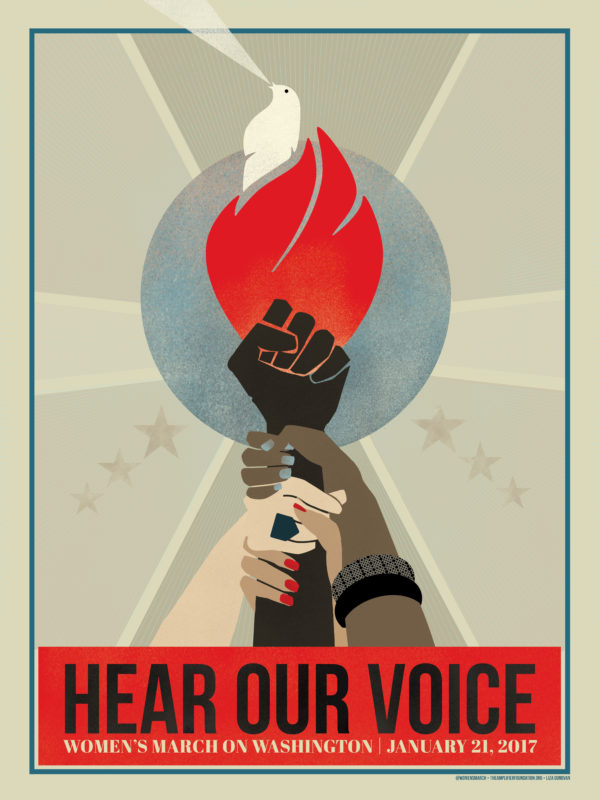

- Art is used to oppose war. Just as governments have commissioned artists to generate support for wars, anti-war organizations have commissioned artists to undermine sympathy for wars and undercut material support for them. Of course, many artists have also independently produced art to agitate for peace.

In their work, these artists have stressed the need to end wars by depicting their brutality, and have tried to generate empathy for their opponents by showing the suffering their opponents experienced at their countries’ hands. They have also used satire to mock the impotency and values of their countries’ leaders.

Unlike art propaganda, anti-war art has historically had artistic value. Well-known artists who have produced important works of art against wars include painters Pablo Picasso and Francisco Goya, photographer Marc Riboud, and muralist Banksy.

- Art, or rather the destruction of art, is used to demoralize opponents during war. Important works of art and architecture have not only been unintentionally destroyed in the course of wars, but they have also been purposely destroyed by combatants as a military strategy to dispirit opponents and invigorate support among adherents by demonstrating the combatants’ strength and resolve. Combatants have also blamed their opponents, falsely at times, for works of art and architecture destroyed in conflicts to demonstrate the affront that their opponents present to their history, values and culture.

Important sites that have been recently destroyed as a wartime strategy include the Grand al-Nuri Mosque and the Baalshamin and Bel temples in Palmyra, Syria.

- Art is looted in the course of war. Looted art has also been used to finance wars. It is impossible to precisely determine the amount of money that ISIS has made from looted art, but Russia has estimated that ISIS nets between $150-200 million per year in the illegal antiquities trade. Looted art has also been used to reward military and political leaders and also has been seized by these leaders to reward themselves.

To prevent stolen art from being used to finance wars, museums and other cultural institutions have offered to house art at risk of being looted until it can be safely returned to the original countries. At the same time, international organizations, including the United Nations and the European Union, as well as individual countries, such as Canada and the United States, have banned the importation of art and antiquities from countries beset by conflicts. Unfortunately, however, these bans are easily subverted and protocols, like those used to certify diamonds as conflict-free under the Kimberley Process, do not exist for art and antiquities.

- Art is used to recover from war. After wars have ended, art has also been used to raise funds for soldiers injured in the course of wars and to provide relief to refugees displaced from them. Art has also been used as part of DDR strategies to provide employment for former combatants and to rehabilitate former combatants emotionally. Artists have even used the weapons of war to manufacture art. Examples of programs dedicated to turning arms into art include the Transforming Arms into Plowshares project and the Peace of Art project, established by Neil Wilford and Sasha Constable, the great-great-great-granddaughter of landscape painter John Constable.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Dr. Jennifer Farrel, Associate Curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for sharing her insights on WWI propaganda posters.