By Erica Chenoweth for Denver Dialogues.

Engaged scholarship takes on a new and urgent meaning when engagement means resistance. Over the past few weeks, many social scientists have mobilized alongside their compatriots to resist the Trump administration’s policies, particularly regarding immigration. In February, a few hundred scholars at the International Studies Association Annual meeting participated in a protest outside of the conference hotel against policies discriminating against Muslim immigrants, threatening the well-being of undocumented people, and barring refugees. Some ISA members also boycotted the meetings in solidarity with Muslim colleagues. The upcoming March for Science will involve thousands of scholars and scientists aimed at confronting anti-intellectualism, anti-scientific reasoning, and denial. And, of course, universities are often sites of resistance more generally, as evidenced by many recent actions in Texas, Arizona, and elsewhere.

It’s a hard time for scholars to be neutral even if they wanted to be. If you are a believer in fact, objectivity, intellectual freedom, scientific progress, radical critiques of power structures, designing sustainable systems in really any technical field, and/or the value of the academic enterprise in general, then you belong to a vilified group in the current American polity. This is especially true for our friends and colleagues who belong to marginalized/frontline communities.

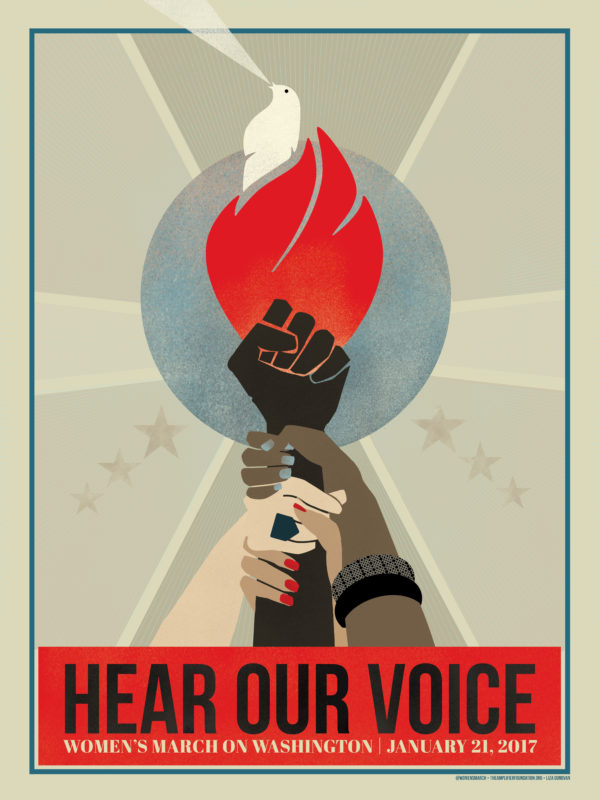

Whether your first foray into activism was the Women’s March on January 21st, or the airport protests a couple weeks later, you may be wondering what happens next for you as a scholar. Most political scientists have little formal training in engaged scholarship – the practice of doing scholarly work that matters for the real world and actively getting it out there. The lack of sites for formal training on engaged scholarship is the rationale for the creation of programs like Bridging the Gap, which cultivates the ability of scholars to influence the policy process through more accessible writing and speaking, the navigation of the policy process itself, and the skill of synthesizing and interpreting current scholarly consensus in ways that meaningfully contribute to public outcomes – particularly when it comes to influencing formal, institutional policy decisions.

As others have discussed in this series before, active participation and involvement in civil society is also engaged scholarship. If you’ve read this far, I’ll bet you’re on board with this. But unlike these more formal conceptions of engaged scholarship, there are few workshops or spaces where people can share wisdom and best practices about, say, how to be a clutch member of your neighborhood’s resistance group.

So, for those wanting to engage in this way, here are a few points to consider. Note that I put these to paper with no real authority other than my own experience, which includes some mistakes in the past. So take what’s useful, and leave behind the rest.

- Get to know what’s already happening in your community. What’s the landscape of different grassroots groups, community organizations, and advocacy networks where you live? Who are your representatives? Have you met them? Do they hold town halls? Joshua Holland has a good piece from last month listing a bunch of relevant orgs. You can also check out my own list here, although it’s primarily Denver-based.

- Don’t duplicate efforts. You may be raring to start your own group. There are cases where this makes sense, but in lots of communities it does not. In fact, there are probably dozens of existing community groups and grassroots organizations that have been toiling along for years / decades and that have profound experience. Don’t reinvent the wheel. Instead, find the existing group that speaks directly to your most pressing concerns and show up for them.

- Show up in solidarity with others when they ask for it. Figure out who in your community has the most urgent needs (marginalized / frontline communities) and show up for them. When they hold trainings or meetings for allies, go there. When they make other requests, show up for them.

- Write down your ethical commitments and share them with some trusted friends for accountability. I did this awhile back, and it has been both a game changer and a lifesaver. Someday I’ll write more about this. Maybe.

- Check out some resources on how to be a good ally. There are a few here, here, and here. On this topic, be a lover, not a fighter. Show up curious and eager to learn from the pros.

- Do not treat people like research subjects—unless they are research subjects. Some kinds of engagement, like participating in protest or counting protests as a public service, are not research and do not require oversight. However, if you are participating in these activities because you hope to someday write a book about your experiences, or you’re counting protests because you want to write an academic article analyzing them, then you are doing research and you need to consult your IRB first. Either way, be clear about what you’re doing there.

- Talk like a normal person. In the immortal words of Yoda, “You must unlearn what you have learned.” If eliminating academic jargon is important in formal policymaking spaces, it is also important in your local group. Learn to talk like a normal person about stuff. The measure of rigor is not based on stringing together sophisticated terms in a sentence. It’s based on clarity of thought. Speaking of which…

- Be impeccable with your commitment to rigor. Do not succumb to the temptation to spread false news, rumors, and speculation because it accords with the way you see the world. Be impeccable in your fact-checking, stick to credible sources, and get to the bottom of stories before you share information within your community. Ask that others do the same.

- Bring what you’ve got to offer. If you’re into crunching numbers, awesome. See if there are ways you can help count things that need counting (e.g., consider joining the Crowd Counting Consortium). If you have substantive knowledge about certain dynamics in the current environment, awesome. See if you can support your community in that way. For instance, if you study migration or human rights and are tapped into a bunch of legal or advocacy networks, now would be a good time to leverage that. If you’re great at programming and know how to make maps with data, awesome. That could be super useful for mapping the landscape of the various groups and organizations in your area, visualizing events data, or creating crowd-sourced apps for rapid response, etc. If you have pedagogical experience facilitating sensitive conversations around power and privilege, awesome. Offer your services if such conversations are not happening where they should be. If you have a ton of contacts in the formal policymaking space (e.g. among government officials, etc.), awesome. Give them a call, ask them how they are doing, and ask what you can do to support them right now. The possibilities are endless!

- Practice extra care around confidentiality. Don’t be snapping photos at a direct action training and posting them on social media unless you are sure that everyone identified in the photo would approve. In fact, it might be best to leave your cell phone (ahem, GPS and auto-recording device) at the door. Don’t talk publicly about whom you saw where. In general, remember that many of the groups you’ll be interacting with are engaging in sensitive work that threatens power and power structures. Use common sense on this one. Respect the need for anonymity and confidentiality when it comes to the people you’re interacting with, but feel free to call attention to their causes among your social networks in a more general sense.

- Feel free to get emotionally vulnerable. This isn’t the most comfortable thing in the world for many of us, but one of the fastest ways to build trust in grassroots groups is to show people your heart. It can be scary, but you’ll be OK.

- Leverage your university’s resources. Do you have meeting space to offer a group? Do you have convening authority to bring people together from around the community? Do you have a deep pool of fellow faculty, students, and staff who want to dive in to conversations about what’s next in the country and world? By all means, offer the space, convene the community, and have the conversations. Now is the time.

- Be a mensch in the workplace. Put into action at work the same basic values the resistance is trying to create in the world. Recognize that you have students, staff, and fellow faculty members, and administrators who are directly threatened by many of the policies that the Trump administration is promoting. Some of these policies are life and death for themselves and/or their families. Show compassion and solidarity whenever you can. And build bridges wherever you can. Wander over to a department you don’t visit much. For example, if you are a social scientist, check out what’s going on in the music department. You might find that folks over there are singing, playing, and dancing the resistance. It’s a great time to reach out and connect with people who are not obvious collaborators.

- Take care of yourself. Already feeling burned out by the new demands on your energies? Take a break and do some things that fill you back up. Full disclosure: this is not my forte, but people tell me to do it all the time. So, I am passing it on.

Have tips, feedback, reflections, or resources you’d like to share on this topic? Put them in the comments section so that everyone can benefit.

1 comment

Well said, Erica. For academics, the university is a kind of safe place where we attempt to ride on top of our material rather than being immersed in it. In becoming activists, we have to acknowledge that we have a stake in these struggles, that we’re participants in history and not mere observers.