Guest post by Ore Koren.

Civil war onset is often correctly associated with weak states, such as Afghanistan. Many blame the failure of coalition forces to win the war in Afghanistan on the weakness of the central government (see, e.g., here, here, and here). Conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, and South Sudan, as well as some Latin American countries, further illustrate this view. But while weaker countries are susceptible to civil war, when we look for places within countries where violence will likely occur, this pattern reverses.

In our study, to be published next month in ISQ, Anoop Sarbahi and I show that this state-centric approach misses a crucial part of the civil war puzzle: conflicts are more likely to erupt where weak states exercise more control, not less.

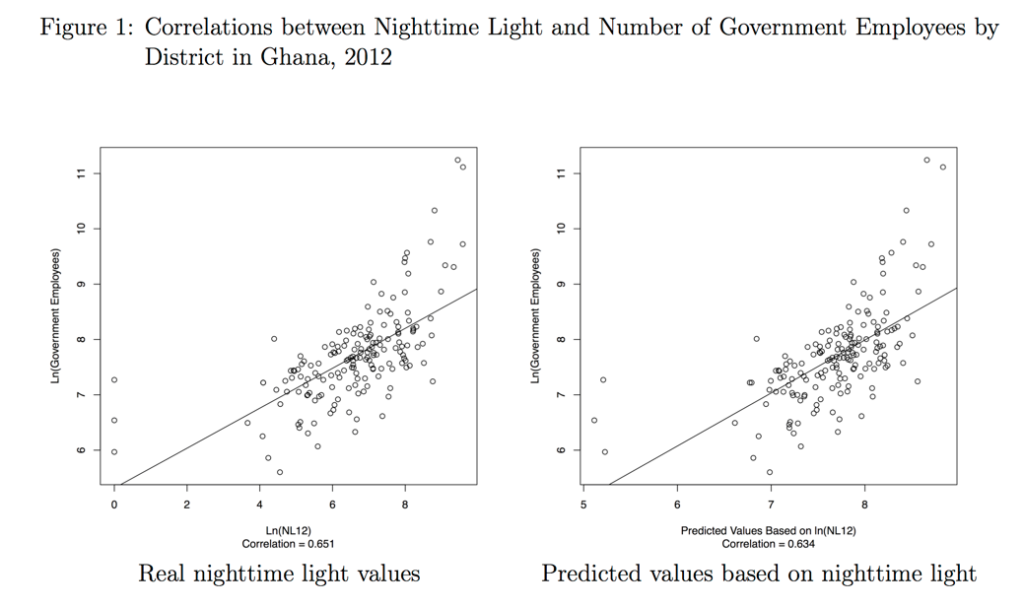

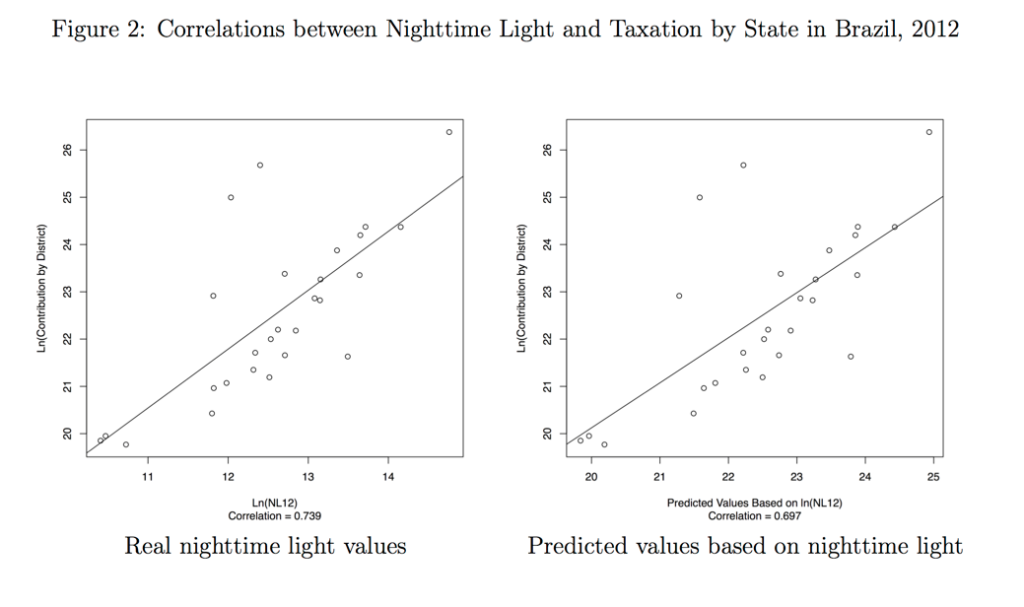

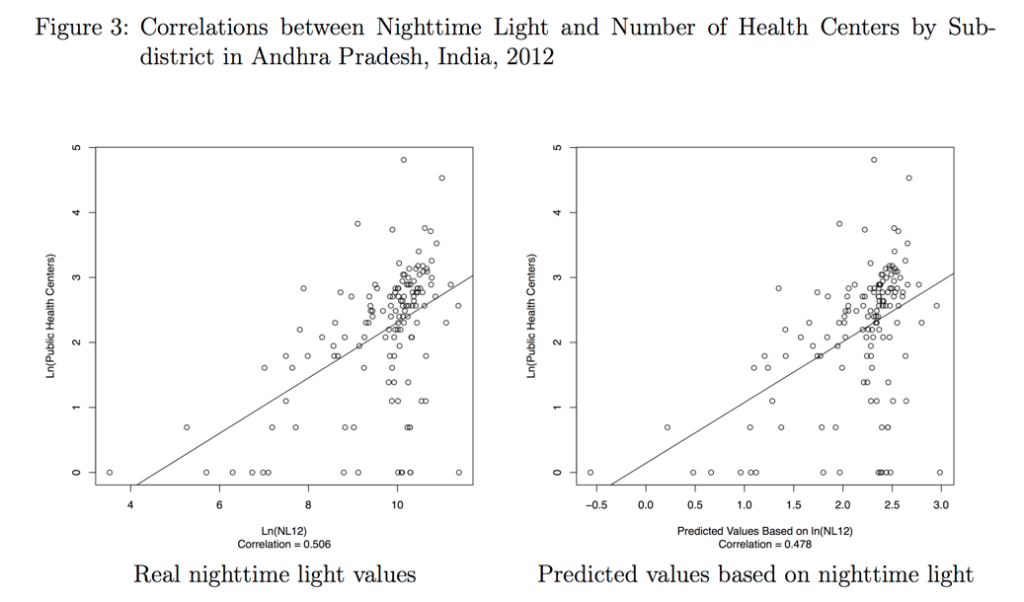

We use nighttime light emission maps, based on NASA satellite images, to identify locations within countries where the government is willing and able to exert influence. Some argue that nighttime light is an effective indicator of various forms of local state capacity, including political mobilization, taxation, economic development, and national security. Indeed, we demonstrate systematically that, at the district level, nighttime light both correlates with and predicts different indicators of state capacity, such as the number of government employees (see Figure 1), revenue from taxation (see Figure 2), and the number of health centers (see Figure 3).

Once we establish empirically that nighttime light emissions are a useful global measure of local state capacity, we test its impact on intrastate conflict. We analyze statistical data of nighttime light over time to see how state capacity is related to civil war onset, not only at the national level, but also within the state, focusing on small geographic areas. At the national level, we find that weaker countries are more likely to experience civil war.

However, within countries, we find that contrary to conventional wisdom, civil wars erupt where there is more nighttime light, not less. We keep observing this result even after we account for areas – countries and regions within countries – where there is no population or where better social and institutional mechanisms exist to manage conflict.

Why does civil war arise where the state has more capacity? Three complementary explanations exist.

The first concerns rebel gravitation, or the notion that rebel groups want to deal the first blow to the state where it hurts the most. Insurgents need to target crucial state infrastructure, penetrate state institutions to influence actors and processes, or control areas where resources are being extracted. For example, in Angola, the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) opened their struggle against Portuguese occupation by launching a deadly attack against police garrisons and a prison in Luanda, the future Angolan capital. And in neighboring Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), forces of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) mobilized urban workers as a tour de force in urban areas.

The second explanation emphasizes elite fragmentation, where different violent factions emerge after the fragmentation of political elites. If these factions are strong, incumbents might fail to continue co-opting political opponents, but also not be able to repress them. Even insurgent groups that aspire to secession still operate in the national or provincial capital, where they use violence if the need arises. This was the case in El Salvador, as well as in Uganda, where Yoweri Museveni and his Popular Resistance Army (PRA) emerged following a conflict of interests with the president Milton Obote.

Finally, in many situations, civil war happens exactly because the state expands its influence into heretofore-ungoverned regions. Expanding the state does not necessarily mean greater integration of the population, but often its disengagement and disenchantment. The locals may perceive such an expansion as constituting a cultural, economic, and/or political threat to their way of life, especially if policies enforce the customs and traditions of the ruling group.

Consider again Afghanistan, this time during the 1970s. Rather than integrating the population, the expansion of government institutions into certain regions was met with resentment and violence, and ultimately contributed to the onset of multiple civil wars. Rebellions in these regions began by attacking state institutions. Four decades on, modern-day Afghans are still paying the price.

The idea that civil war onset is related to poor administrative and institutional control of their peripheries has informed US and international security strategies (see, e.g., here, here, and here). Indeed, the notion of winning the “hearts and minds” of civilians by promoting democratization and economic development in order to promote peace has captivated foreign policy makers and military officials since at least the 1990s.

But it is exactly these miscalculated moves toward hastened institutional expansion that often generate resentment, and more conflict. Indeed, it might very well be that the idea that we can win “hearts and minds” is simply an ignis fatuus in many situations. Promoting development and capacity within states can and will lead to more civil war. That does not mean we should not pursue these aims, because in the long run, political openness and high economic development will have a pacifying effect. But for Afghanistan and other low capacity states, things might get worse before they get better.

Ore Koren is a US Foreign Policy and International Security Fellow at Dartmouth College, a PhD Candidate at the Department of Political Science, Minnesota, and starting August 1, 2018, an Assistant Professor at Indiana University, Bloomington.

2 comments