Guest post by Juan Masullo and Davide Morisi.

The same night Mexico’s President-elect, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO), won the election, he announced a radical shift in the country’s “war on drugs”. “The failed crime and violence strategy will change,” he proclaimed, referring to the strategy of militarized public security initiated by President Calderón in 2006. Claiming that Mexico needs abrazos no balazos (hugs, not gunshots), AMLO made clear his intention to stop the militarized war on drugs and hand the security job back to professionally trained police. But can he convince Mexicans that they will be more secure once the military is taken off the streets?

Moving away from a heavy-handed, military-first approach is no easy task. Important sectors of the Federal Government continue to argue that militarization has been effective, and in December of last year the Congress approved a bill that “institutionalizes” the role of the army in fighting organized crime. Moreover, while notable civil society organizations such as Mexico United Against Delinquency openly oppose militarization, the army is still one of the country’s most trusted institutions. According to 2017 LAPOP data, around two thirds of Mexicans highly trust the armed forces.

The coexistence of high levels of violence and strong support for militarization is puzzling. On the one hand, supporters of militarization contend (sometimes implicitly) that the ultimate goal of military operations (i.e. curtailing drug-related crime) justifies the many lives that have been lost in the process. On the other hand, opponents argue that killing human lives can never be acceptable. What do Mexican citizens really think?

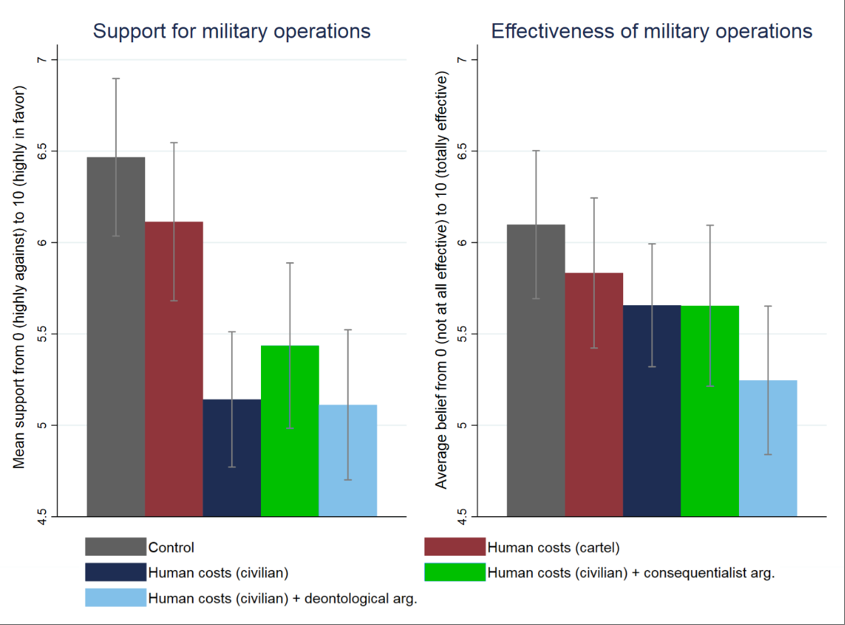

We attempted to figure out when Mexican citizens would be willing to support a military approach to security and when they would not. To do this we conducted an experiment together with CIDE’s Social Science Experimentation Unit (UECS-Lab). Around 700 mostly young and educated respondents from three different Mexican cities read a short vignette describing a fictional, yet realistic, successful military operation against a drug lord. Some of them were reminded that the operation involved human costs among either members of the cartel or civilians. In addition, some participants read a short text presenting either an argument in favor of–or against–military operations. Then we asked all participants how much they supported the use of military operations to combat organized crime, and how effective they thought these operations were.

We found that support for (even successful) military operations against organized crime is lower when operations involve human costs. This was to be expected. But, interestingly, we also learned that this is the case only when casualties are civilians. Moreover, we found that support for military operations that harm civilians remain significantly lower even when these operations are justified in light of the ultimate goal of eradicating organized crime.

However, the fact that military operations might kill civilians does not alter whether Mexicans believe these operations are effective. Participants considered the fictitious military raid successful even when it involved civilian casualties. However, they did consider that the same operation was less effective when reminded that “life is sacred”. In short, moral arguments seem to persuade people that militarization is not an effective strategy to combat organized crime, even when its stated goals are achieved (e.g., toppling a drug lord).

Figure 1. Effects of human costs and information on support for militarization

The Way Ahead

AMLO will take office on December 1st. He has less than two months to flesh out his new security plan and gain public support for it—an effort that is already underway in his “public peace-building forums”. Our research suggests that, in order to gain citizens’ support for the process of de-militarization, the campaign for a new security approach should be accompanied by a public/social narrative that creates awareness of the human costs of militarization—and which highlights the moral principle of respecting life. Citing figures on how many people have been killed in the country since the “mano dura” approach was embraced—as several human rights organizations have done so far—might not be enough to create the legitimacy needed for changing direction on security matters. However, the new administration may be able to gain support for its new strategy by stressing the sacred value of life and the fact that a large portion of these casualties involve civilians who are fully unrelated to drug and cartel activity.

*We are grateful to CIDE’s Social Science Experimentation Unit for supporting and funding this project, and to Alberto Guevara and Mariano Sánchez-Talanquer for useful advice.

Juan Masullo is Lecturer in the Department of Politics and International Relations and Research Associate at the Changing Character of War Centre at the University of Oxford. He is also affiliated with the Methods Center at BIGSSS. Davide Morisi is Assistant Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Vienna.

1 comment