Guest post by Patrick Pierson.

The African continent will see two dozen elections in 2019. While many observers herald this year’s surfeit of political contests as a sign post of the “Third Wave of Democratization,” others are less optimistic, noting the violence that often accompanies putatively democratic elections across the continent. Indeed, the causes and consequences of electoral violence in Africa are currently at the fore of work in both academic and policy circles. And the focus on electoral violence is warranted—in 2019 alone, violence has marred the political process in countries as diverse as Senegal, Nigeria, and Malawi, among others.

While the current wave of political violence is troubling, it is far from unprecedented—physical violence has tainted more than one-in-five elections worldwide in the post-Cold War era. Despite the prevalence of such overtly contentious elections, few studies have examined the broader causes and effect of political violence, especially in new and emerging democracies. Addressing these challenges, recent studies document the uptick in politically-motivated violence that often accompany electoral cycles (see here, here, and here); though important, the explicit focus on election-day violence runs the risk of missing broader trends in political violence. Here’s why.

Research shows that election-related violence, both in Africa and elsewhere, is not incidental to the political process, but instead reflects a strategic, instrumental calculus by political elites to turn the electoral tide in their favor. Threats—or the actual use of—violence can increase politicians’ electoral competitiveness by influencing voter behavior and turnout (see here and here). Electoral violence has also been linked to a number of broader structural and institutional characteristics, including the ethnic composition of states, various types of electoral institutions, and regime type.

These approaches, however, typically examine only one type of political violence—namely, the use of violence by politicians to mobilize supporters and/or suppress the opposition. While important, this is not the only form that electoral violence may take and, in many instances, is not the most common form of coercive contestation in democratic states.

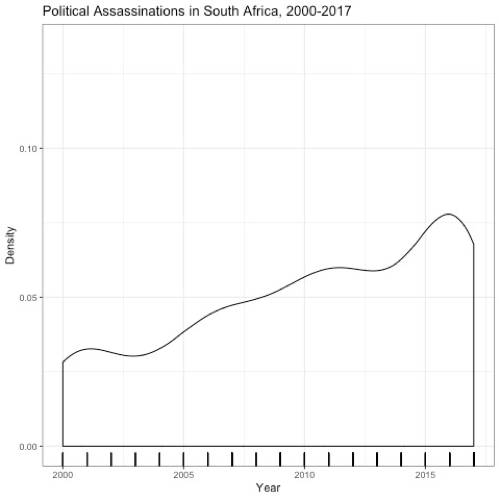

My recent research explores intra-elite violence in democratic states, an oft-overlooked aspect of political contestation that has recently claimed lives in countries as diverse as the Philippines, Mozambique, Mexico, and Nigeria. More specifically, I explore more than 260 political assassinations in South Africa from 2000 through 2017. Figure 1 documents the rising tide of targeted political killings in recent decades.

Attacks on local politicians—by other politicians—recently reached such a fever pitch in the KwaZulu-Natal province that the government convened a commission to look into the nature of the violence. Contrary to much of the existing work on electoral violence, the commission’s findings document fighting within the ruling African National Congress (ANC) as the underlying driver of the assassinations.

In a country with unemployment rates consistently pushing 30%, securing a position as a local councilor represents an economic windfall for many young, entrepreneurial politicians. Access to—and significant control over—the disbursement of local development funds further provides politicians with ready-made access to a vast patronage network that confers vast economic and social leverage. In this setting, political violence is rampant, but represents a qualitatively different type than what is typically studied by policymakers and academics.

For many observers, the unseemly behavior of local politicians is not surprising in a country reeling from accusations of “state capture” by private interests under the prior administration of President Jacob Zuma. Citizens are polarized on the issue, however, as evidenced by last week’s violent disruption of a book launch detailing ANC secretary-general Ace Magashule’s murky dealings and alleged involvement in corruption. These developments raise all sorts of important questions about the role of violence in democratic regimes and citizens’ choice to (not) sanction leaders implicated in malfeasance.

More broadly, current trends in South Africa encourage a renewed exploration of the challenges faced by democratic regimes in an increasingly polarized political climate. In a world where politicians can shoot people in the middle of Fifth Avenue and not lose voters, the South African case serves as a reminder of the need for strong institutions that curtail political misbehavior and encourage democratic accountability in the midst of heated political contests. If Google searches are any indication, South Africans are concerned about the potential for electoral unrest as they head to the polls next month for general elections. And while the focus on securing a peaceful election day is important, every day, quotidian political accountability is needed to ensure democratic stability in the years ahead. It’s a lesson that all democratic citizens, not just South Africans, would do well to remember.

Patrick Pierson is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at Emory University and the Managing Editor of Political Violence @ a Glance. You can follow him on Twitter @plpierson.