Guest post by Betcy Jose and Christoph Stefes.

White House National Security Advisor John Bolton recently declared, “In this administration, we’re not afraid to use the phrase ‘Monroe Doctrine.’” The Monroe Doctrine harkens back 200 years to a policy that captures the idea that a hegemonic power holds dominion over a particular geographic region—its sphere of influence—where it serves as the sole arbitrator of the rules of the game. Bolton likely referred to the doctrine’s Roosevelt corollary where, “the United States was justified in exercising ‘international police power’ when there was unrest in Latin America.”

In explicitly referencing this doctrine from the past, Bolton seemingly took a page from the playbook of the Game of Thrones’s (GoT) Night King, bringing back to life things once considered dead. As President Obama’s Secretary of State John Kerry stated, “’The era of the Monroe Doctrine is over. The relationship that we seek and that we have worked hard to foster is not about a United States declaration about how and when it will intervene in the affairs of other American states.’”

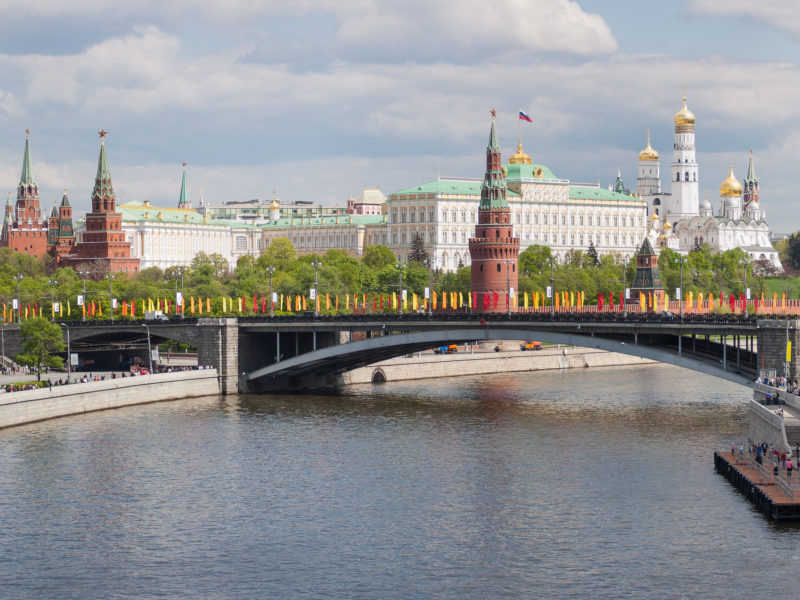

Yet, the United States wasn’t the only state to recently channel the Night King, converting doctrinal corpses into zombies. Russia tried to do the same with the rationale for its Crimean intervention. At the time, Russia claimed it was a humanitarian mission, as the violence there, “is a real threat to the lives and health of Russian citizens” in Ukraine. By launching this intervention without UN Security Council authorization in a former Soviet republic, Russia not only violated the UN’s humanitarian intervention doctrine, Responsibility to Protect (R2P), it also seemed to say sphere-of-influence politics was back from the dead.

Apart from the GoT-like behavior, what makes US and Russian rhetoric surprising is it contravenes common perceptions of the relationships autocracies and democracies have with global norms. Focusing just on autocracies, they are often the poster children of bad behavior: egregiously violating their own citizens’ rights, supporting similar behavior in other countries, and obstructing efforts to create new rights. So it is no wonder that countries and organizations considered human rights champions strongly condemned Russia’s humanitarian claims in Crimea as hypocritical and cynical. Former US Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power rebuked it, saying, “What is happening today is not a human rights protection mission or a consensual intervention. What is happening today is a dangerous military intervention in Ukraine. It is an act of aggression.”

Yet the historical record suggests that the link between Russia and human rights is more complex than appears at first blush, as its humanitarian support for particular ethnic, religious, and linguistic communities over the centuries indicates. Some of these endeavors included violating other sovereigns’ borders to protect Russians and Russian speakers and took place during a time when regional powers did as they wished within their domain. Seen in this light, Russia’s humanitarian gloss on its Crimean intervention seems less spurious, even if it doesn’t articulate a cosmopolitan ethos or ignores the plight of Russians in Russia.

Refusing to abandon this humanitarian justification, despite the imposition of sanctions, also intimates a stronger normative commitment than more critical analyses might imply. This commitment involves a regional alternative to R2P, a norm that allows it to unilaterally intervene in its backyard without UN Security Council approval. At the same time, Russia’s repeated vetoes on UN resolutions to intervene in Syria also indicate it is not ready to invalidate R2P and the influence it offers Russia on the global stage.

In this way, Russia’s actions are consistent with hegemons of old throwing their weight around, dictating one set of rules for their sphere while pushing another set of rules elsewhere. In other words, Russia is demanding to be treated as the great power it thinks it is. And with some declaring the liberal order’s coming collapse, it is unsurprising that Russia would exploit the current situation to contest existing norms and advance alternatives (even if they are zombie norms), as a great power would. Russia’s brand of interstate aggression seems to even resonate with those who once opposed it. Bolton’s invocation of the Monroe Doctrine and US threats to militarily intervene in Venezuela are a case in point.

But none of this implies these challenges will be successful. In the case of Russia, by adopting a more nuanced understanding of its motivations—one that incorporates its need to be recognized as the great nation it thinks it once was and is and considers the causes it prioritizes—Western policy-makers may be better able to influence its behavior. So far, Western foreign policy analysts and officials mainly understood Russian normative justifications in Crimea as a thinly veiled attempt to illegally pursue material (both military and economic) interests. Consequently, they advocated for economic sanctions and a military buildup in Russia’s neighborhood to deprive Russia of any gains it might have reaped. However, if these punitive measures were designed to force Russia out of Ukraine, they have largely been futile.

To more effectively induce behavioral change, Western policy-makers need to entertain the possibility that Russia may also be motivated by non-material factors like identity and a deep commitment to particular causes that material cost-benefit analyses may not influence. The international community would not give away too much if it more meaningfully included Russia in shaping the rules of the international system. Former US Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul advises future US presidents to better “integrat[e] Russia into the West than their predecessors have done.” But why not start now, for example with discussions on how best to modify R2P in the troubling aftermath of the Libyan and Crimean interventions?

Further, while the West cannot grant Russia free reign in its neighborhood without abandoning a normative bedrock of the international system, it also has to refrain from its own spheres-of-influence politics. In other words, practice what it preaches.

Russia is here to stay. A carrots and sticks approach based exclusively on materials interests may not always be effective. Yet a more expansive toolkit, one that considers Russian self-identity and values, may increase the chances to maintain global stability and avoid resurrecting dangerous policies from the past.

Betcy Jose is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Colorado-Denver. Christoph Stefes is Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Colorado-Denver.