Guest post by Sally Sharif and Dayron Yegrail.

Colombia’s peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—People’s Army (FARC-EP) was widely hailed as a diplomatic triumph. However, even before four top commanders of the former rebel group called for rearmament in late August, the agreement was increasingly described as “fraying”, “strained”, or “not working.”

Our research shows that these views are misguided for two reasons. First, the metrics used to call attention to a “frayed” peace agreement are flawed. Second, they ignore the original intentions of the two parties in signing the peace agreement in 2016. Our interviews with Common Alternative Revolutionary Force (FARC) senators (members of FARC’s newly-formed political party), 120 ex-combatants in five demobilization camps, and with former mid-level commanders show that the agreement is as strong as it was deemed to be when it was signed and that it is serving a larger political purpose, especially for the FARC.

The peace agreement is not fraying for the FARC: it has managed to keep most of its former combatants united in the twenty-four demobilization and reintegration camps (Territorial Spaces for Capacity-Building and Reintegration, ETCR), forced the government to sign the transitional justice system (Special Jurisdiction for Peace, JEP) into law, and highlighted the government’s impotency in addressing the country’s social and economic grievances. Meanwhile, the FARC is continuing its political struggle in the countryside. The peace agreement has changed Colombian society, its expectations of the government, and the nature of its democracy.

What does it mean for an agreement to fray? A peace agreement fails if one or both parties officially withdraw from it. The peace agreement with the FARC hasn’t failed; however, we can’t say it has succeeded either. The Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies reports that only 23% of the agreement has been fully implemented.

In evaluating a peace agreement, public perception matters: including innumerable provisions in an agreement creates great expectations among the population, making it increasingly difficult to ensure satisfaction during implementation. The Colombian government agreed in the peace agreement to provide infrastructure, security, and welfare services to populations in municipalities with extreme poverty, with 54.85% of their basic needs not met. These provisions require major developmental projects in the post-conflict era, unachievable in a three-year period. It is thus misleading to claim that the peace agreement is fraying because people who live in conflict zones have not experienced a dramatic change in their living conditions.

None of this comes as a surprise to the former rebel group. FARC senators, who were present at the negotiations in Havana, told us the FARC never considered the Colombian government capable of implementing all the provisions mapped out in the peace agreement. In fact, the FARC was fully aware that (in their terms) a capitalist state is not interested in delivering on their side of the bargain, i.e., attending to the needs of the most discriminated classes of society. But by compelling the government to admit to these existing problems and promising to find solutions to them, the FARC has ingeniously managed to present to struggling Colombians an image of a failing government.

The extraordinary homicide rate among human rights activists and community leaders is one of these highlighted problems. The negotiation period with FARC-EP saw as many social leaders killed as under the current right-wing President, Iván Duque: 78 murders were reported in 2013 and 77 in 2018. Why are the Colombian people only now paralyzed by the phenomenon, showing discontent through anti-government protests? Carlos Antonio Lozada, a FARC senator and de facto head of the political party, told us the murder rate has been one of the externalities of the peace process and is decisive for the success of FARC’s political project.

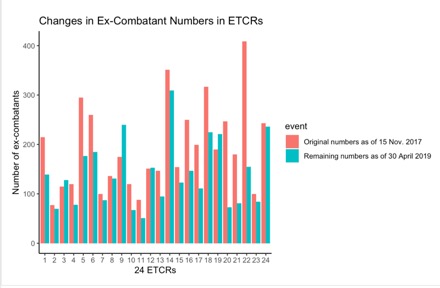

Various reports have associated failure in the peace agreement with ex-combatants leaving the ETCRs. The data we received from the latest census by the Colombian Agency for Reintegration (ARN) show that ETCRs across the country have experienced varying stay rates. Some of them house more ex-combatants now than they did in the first year of the peace process.

It is thus misguided to judge a peace agreement by the proportion of provisions that have—or have not—been implemented. The FARC has won through the peace deal. Almost 90% of FARC ex-combatants we interviewed do not think of the FARC as a potent political force on the national level—almost 85% say they would be content simply if the mayor of a municipality or a member of the municipality council is a FARC member. Across Colombia, about 21 FARC members are running in local elections scheduled for October 2019. For the FARC, the peace agreement has been a success if it manages to mobilize people in the countryside to elect its members to local political offices. This, after all, was the core of FARC-EP’s founding mission 52 years ago.

Sally Sharif is a Visiting Scholar at the Universidad de los Andes and a PhD candidate in Political Science at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. Dayron Yegrail is a student in Economics at the Universidad de los Andes.