Guest post by Zhao Li and Richard DiSalvo

Fueled by unsubstantiated claims of widespread election fraud, supporters of President Donald Trump stormed the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, in a violent attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election result. On the same day, 147 Republican members of Congress voted to object to electoral college counts.

In the wake of the Capitol insurrection, corporate America was under tremendous pressure to cut off campaign contributions to these “Republican objectors.” This mirrors a broader trend in public opinion: people across many countries, including in the United States, increasingly expect large companies to speak up about contentious socio-political challenges.

In January and February 2021, CNN surveyed 280 companies on the Fortune 500 list that contributed to Republican objectors’ campaigns in 2019–2020 through their corporate political action committees (PACs). One hundred and fifty-seven surveyed companies declined to announce any changes in their PAC contributions post-insurrection. This wasn’t a surprise to scholars who study corporate money in US politics—companies have traditionally viewed PAC contributions as a means to buy lobbying access and regulatory favors from policymakers rather than an expression of corporate advocacy. What was unprecedented, however, was the number of America’s largest companies that did respond affirmatively to the CNN survey: 87 companies promised a pause in all federal giving, and 36 companies specifically pledged to withhold PAC contributions from Republican objectors.

Why did some companies pledge to boycott Republican objectors in their PAC contributions rather than remain silent or announce a blanket pause in PAC contributions? Moreover, which firms have actually reduced their PAC contributions to Republican objectors since 2021?

In our forthcoming publication in the American Political Science Review, we show that corporate stakeholders—e.g., employees, consumers, and shareholders—can influence their corporations’ PAC contributions. Many stakeholders expect corporate PACs to support politicians who align with their partisanship or ideology. Though few employees, consumers, and shareholders hold formal decision-making power in corporate PACs—which are generally controlled by companies’ government-relations specialists—these stakeholders can indirectly shape corporate PAC contributions through markets (e.g., boycotts, divestment, personnel turnovers) and governance (e.g., shareholder proposals and corporate PACs’ reliance on employees for fundraising).

Echoing partisan divides in US opinion on whether the Capitol insurrection was a threat to democracy, we found that companies with more Democratic-leaning stakeholders—based on their campaign contribution histories and political Twitter networks—were more likely to announce a freeze in PAC contributions targeting Republican objectors, but no more likely to announce a blanket pause in PAC giving. These patterns remained regardless of the firms’ market and political characteristics.

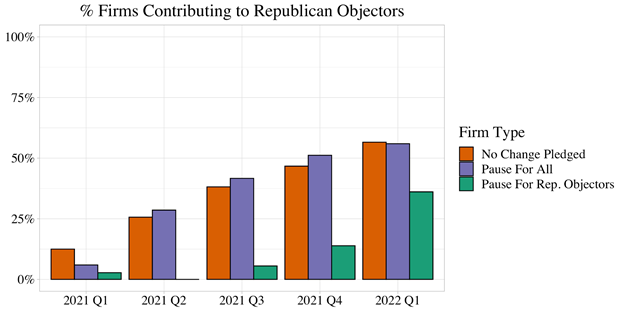

Did companies follow through with their promises and demonstrate durable changes in their PAC contributions? In our analysis we found that during 2021, firms that pledged to freeze PAC contributions to Republican objectors largely kept their word, and did not appear to circumvent their pledges by channeling money to Republican objectors through more covert (though still observable) avenues. By contrast, many firms that either made no pledge or pledged to halt all contributions equally had restored their support to Republican objectors’ campaigns by the second quarter of 2021.

By 2022, a nontrivial fraction of firms that had pledged to freeze PAC contributions to Republican objectors had made at least one donation to these legislators, though still at a lower rate than that of other firms.

In short, the partisan orientation of corporate stakeholders seems to play a key role in determining which firms made—and kept—meaningful pro-democracy promises.

Can such corporate advocacy deter anti-democratic conduct and political violence? On the one hand, corporate America’s collective response to the Capitol insurrection influenced Sen. Mitch McConnell’s decision to denounce President Donald Trump following the insurrection. On the other, Republican objectors, relative to other congressional candidates, saw a greater surge in contributions from individual—particularly small-dollar—donors in 2021. Media reports suggest that Republican objectors may have strategically adapted their campaign solicitation tactics and amplified their attacks on “woke corporations,” which seemed to resonate well with small donors. As corporate PAC contributions become a diminishing share of total campaign fundraising for congressional candidates, and especially for more radical candidates, corporations’ ability to hold politicians accountable for protecting democratic institutions and norms may be swept away by the tide of a changing campaign finance landscape.

Zhao Li is an Assistant Professor of Politics and Public Affairs at Princeton University. Richard DiSalvo is a Lecturer and Associate Research Scholar at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs.