Guest post by Benjamin S. Case

Riots are a significant feature of the political landscape. In the past year riots dominated headlines, sparked nationwide debates, and changed political conversations. Amidst the deterioration of American democracy, and with many asking how social movements from below can change institutions, it is critically important to talk about riots in accurate and appropriate terms, especially as we consider what tactics “work” and which do not.

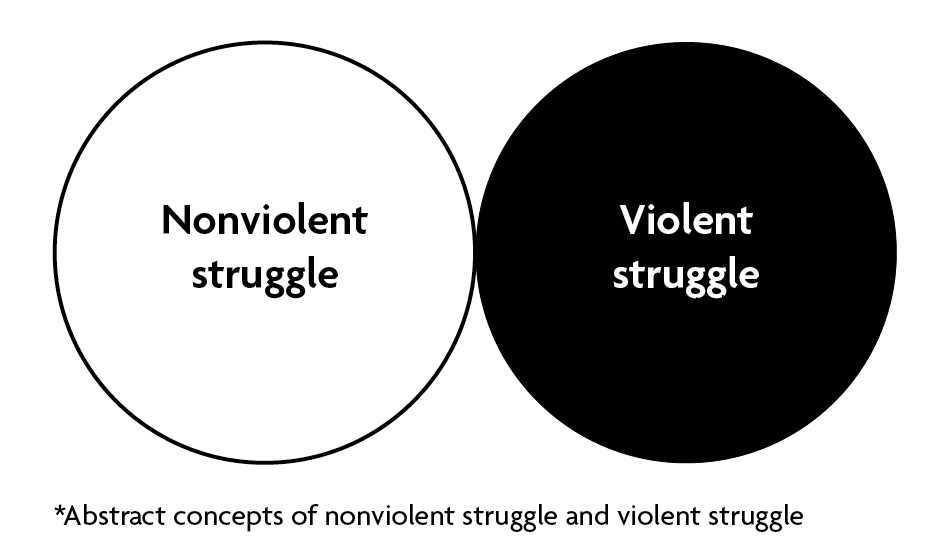

“Riot” generally refers to violent protests, or protests in which some participants threaten or use physical force to damage property or people. Protesters throwing projectiles or scuffling with police transforms a nonviolent protest into a violent one. However, just because riots involve physical force does not mean they are interchangeable with other forms of political violence, like armed warfare.

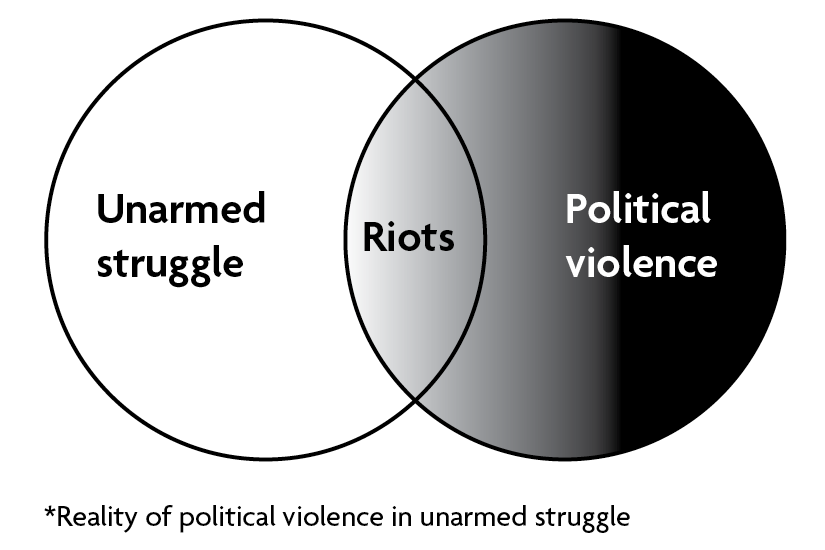

Prominent research argues that nonviolent protest is the most effective method for social movements to pursue causes, but the reality is more complicated. The research that forms the empirical basis for this claim does not account for low-level violence; it compares primarily armed conflict with primarily unarmed conflict, and refers to unarmed campaigns as “nonviolent.” But a movement being primarily unarmed is not the same as being nonviolent. For example, the 2011 revolution in Egypt is categorized in this research as a “nonviolent campaign” even though it involved fierce anti-police riots. In fact, the vast majority of unarmed movements have involved major riots.

To understand social change from below, we must account for violent protest as part of that process.

Which works better: riots or nonviolence?

So, which is more effective: violence or nonviolence? One answer is: we don’t know. That is because the main research on the subject compares protest movements to warfare and is widely misapplied to unarmed violence within protest movements. The past few years, however, have seen the publication of a number of relevant empirical studies—sometimes with contradictory results that both clarify and complicate the answer.

Some argue that riots lead to negative backlashes for movements at the polls. One recent study tested simulated “counterfactual scenarios” for the 1968 election, arguing that riots led some people in white neighborhoods to vote Republican, resulting in Richard Nixon’s election. Based on these findings, some argued that violent protests in 2020 could lead to a Trump electoral victory or a coup.

On the other hand, research on the 2016 election found that Black Lives Matter protests—including both nonviolent and violent actions—positively mobilized Black voters but did not significantly impact white voting behavior. The 1992 riots in Los Angeles appear to have led to a liberal shift in policy support among both Black and white voters.

Another argument centers on the ways violent protest shifts public perception of a movement. But the impact of contentious protests on public opinion has a lot to do with who is protesting and why. For example, 90 percent of Americans opposed the Capitol riot on January 6, but in June, polls showed that 54 percent of Americans thought the burning of the Minneapolis police station was a justified response to the police murder of George Floyd. Both events involved destruction of property and fights with police, which suggests that public support or antipathy was driven less by tactics than by the identities, social position, and political orientation of the protesters.

On a deeper level, approaching protester violence and nonviolence by asking which “works better” is asking the wrong question. First, it elevates abstract notions of tactics over context, and second, it presupposes that more and less physically forceful protests are mutually exclusive and inherently opposed forms of action, when more often than not, they are linked.

Historically, violent protest has accompanied moments of uprising, and statistically riots are associated with increased nonviolent demonstrations. Violent protests, like any tactic, have a variety of effects depending on the context. One recent study found that “extreme protest actions,” which include riots in addition to disruptive nonviolent actions like blocking traffic, come with a trade-off for activists: they enable movements to effectively pressure institutions and draw attention to issues, but also tend to reduce popular support. How these effects weigh into the short- or long-term goals of a movement vary by case. Many studies only consider movements that make claims to government power, but of course many movements have other goals, differing short-term and long-term goals, or internal disagreements about goals.

Finally, some effects are difficult to measure. For example, even when they do not achieve immediately recognizable results, images of riots—or nonviolent protests—can serve as powerful symbols of resistance. If an action fails to achieve material goals today, but inspires a new generation of activists or policy proposals tomorrow, should we say it was effective? It depends. Either way, riots are not a theoretical inverse of nonviolent protest; they are a complex and multifaceted part of unarmed conflict.

Riots in focus

The terms “violent” and “nonviolent” can easily slip from categories of political action to moral claims. Speaking about riots in particular is inextricably tied to conversations about structural violence. The effects riots have on movements and social change is highly contextual, but it is also an empirical question that is distinct from moral positions on violence and nonviolence in the abstract.

It is not useful to talk about riots as abstract manifestations of violence, and we cannot rely on research about armed warfare to inform our opinions. Riots are part of the repertoire of protest movements, and, in our political moment, it is crucial that we talk about them with due nuance and context.

Benjamin S. Case is an affiliate faculty member in the Department of Sociology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, an affiliate with the Resistance Studies Initiative, and an editor at Journal of Resistance Studies.