Guest post by Pearce Edwards and Patrick Pierson.

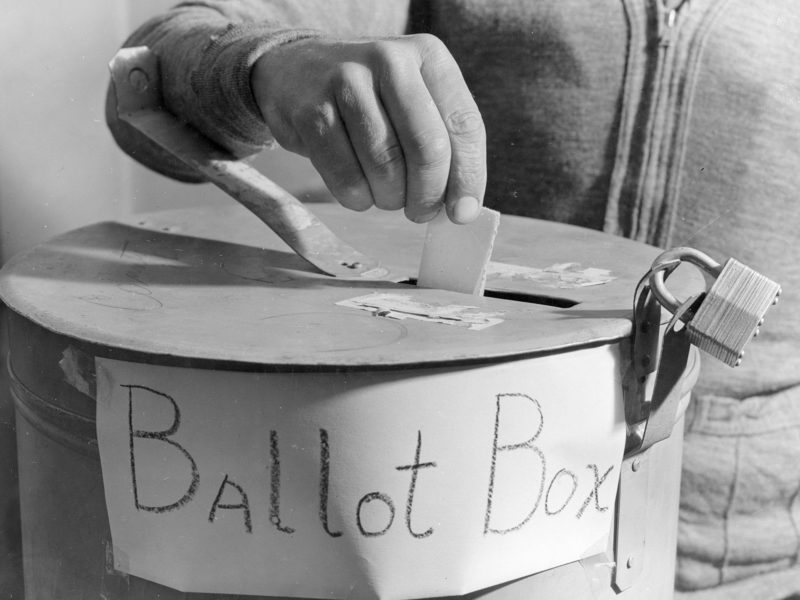

With less than two weeks to go until Election Day in the United States, concerns about escalating political violence remain front and center. The US is not alone. Around the globe, dozens of national elections are scheduled between now and the end of the year, and the shadow of violence looms large in many places.

With a contentious presidential election slated for December, Ghanaian leaders continue to call for peaceful elections in the face of ongoing threats from politically aligned “vigilante groups.” In neighboring Côte d’Ivoire, President Ouattara’s controversial bid for a third term in office has many concerned about the potential for widespread political violence later this month. In South America, Chile continues to experience widespread political protests—some of which turned violent—in the lead up to a hotly contested referendum slated for October 25th.

While the prospect of political violence persists in many democratic countries, our understanding of how violence impacts political behavior—such as voter turnout and vote choice—is surprisingly fragmented.

Some studies (see here, here, and here) suggest that threats of political violence around elections exert a dampening effect, decreasing turnout by raising the expected costs of heading to the polls. In other words, if voting involves significant risks to your personal safety, you’re more likely to simply stay home. Others argue that violence has no meaningful effect on voter behavior, and can even induce a backlash, whereby voters actively punish political actors for engaging in violence.

In a new working paper, we find that the impact of violence depends on who is targeted. Take the example of Argentina. Beginning in 1969, with the country under military dictatorship, popular violent uprisings galvanized the far left, particularly nascent guerrilla movements that believed armed struggle could depose the military, bring former leader Juan Perón out of exile, and restore him to the presidency.

Sensing the military’s regime increasingly tenuous grip on power, a number of left-wing movements—most prominently, the Montoneros, a Peronist organization that sought revenge on Perón’s old enemies in the military—went on the offensive. In a bid to quell the unrest, new military dictator permitted the Peronists to run in general elections called for in March 1973, but prohibited Perón himself from appearing on the ballot.

The results were clear: the Peronist party, who ran Héctor Cámpora under the popular slogan “Cámpora for office, Perón for power,” won nearly 50 percent of the popular vote. Two months later, Perón returned to Argentina permanently, Cámpora resigned, and new general elections were scheduled for September in which Perón would stand as the candidate for the Justicialist Front.

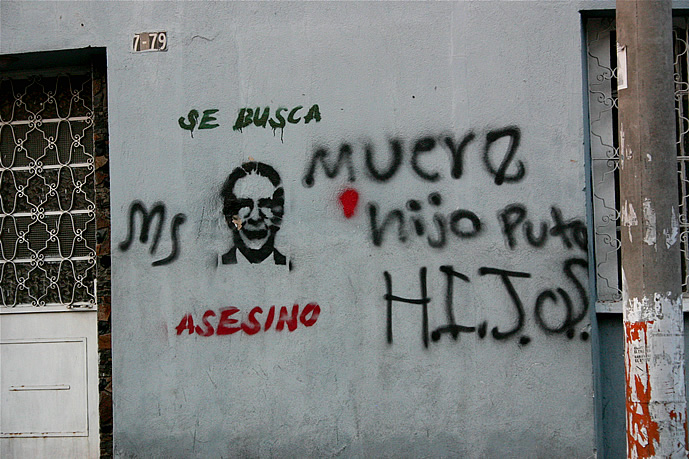

Against this backdrop, left-wing militant organizations decided to press their advantage, stepping up a campaign of violence against elites from the former government, including military officials, business executives, and journalists, among others. Between the March and September elections, these groups targeted dozens of elites associated with the political right, represented in the elections by the Popular Federalist Alliance (APF), in acts of armed propaganda, “transmitting political messages through violence of a spectacular, yet measured, nature.”

Less concerned with deterring voters from turning out at the polls, the militant groups used violence to delegitimize the political opposition and demonstrate their ability to inflict costs on political opponents. By portraying the political right as weak and ineffectual, militants hoped that voters would lose faith in the political right, and the APF specifically.

The result? APF vote share decreased by 2.7 to 4.2 percentage points in Argentine departments that experienced violence in the inter-election period, compared to departments that did not experience violence. However, the violence did not appear to affect voter turnout; rather, we find that Argentines who presumably would have voted for the APF shifted their votes to other, ideologically proximate parties.

The takeaway: while political violence remains a real possibility for upcoming elections in a number of countries, the effects of such violence are likely to vary based on context and intent. In some instances, armed actors may turn to violence in an explicit effort to decrease turnout among targeted populations. However, violence around elections is often more symbolic in nature, a signal of the targeted party’s weakness and the perpetrator’s ability to sow unrest and impose costs on political rivals.

Moreover, the perceived “success” of political violence in the Argentine case proved illusory. The reaction of a demoralized right-wing establishment to the actions of left-wing armed groups fomented a cycle of violence that, in 1976, culminated in a military coup. Over the next seven years, 30,000 Argentines were killed or disappeared in the name of national security.

In the end, Perón’s Faustian bargain with his armed supporters proved all-too-predictable. Like all such bargains, in time, the short-term gains paled in comparison to the long-term costs—not just for Peronists, but for all Argentines. Once the Pandora’s box of political violence has been opened, no one is safe. The defense of electoral integrity is in everyone’s best interest.

Pearce Edwards is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at Emory University. Patrick Pierson is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at Emory University.