By guest contributor Angela D. Nichols and permanent contributor Christopher J. Fariss

Access the Spanish translation here.

Since the signing of the peace agreement in 2016, 249 FARC ex-combatants have been killed and at least another 272 have reported threats revealing a systematic pattern of violence in Colombia. Once a rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), and now a political party, the Common Revolutionary Alternative Force (FARC), the FARC continues to demand answers and increased security from President Duque’s administration.

What is happening?

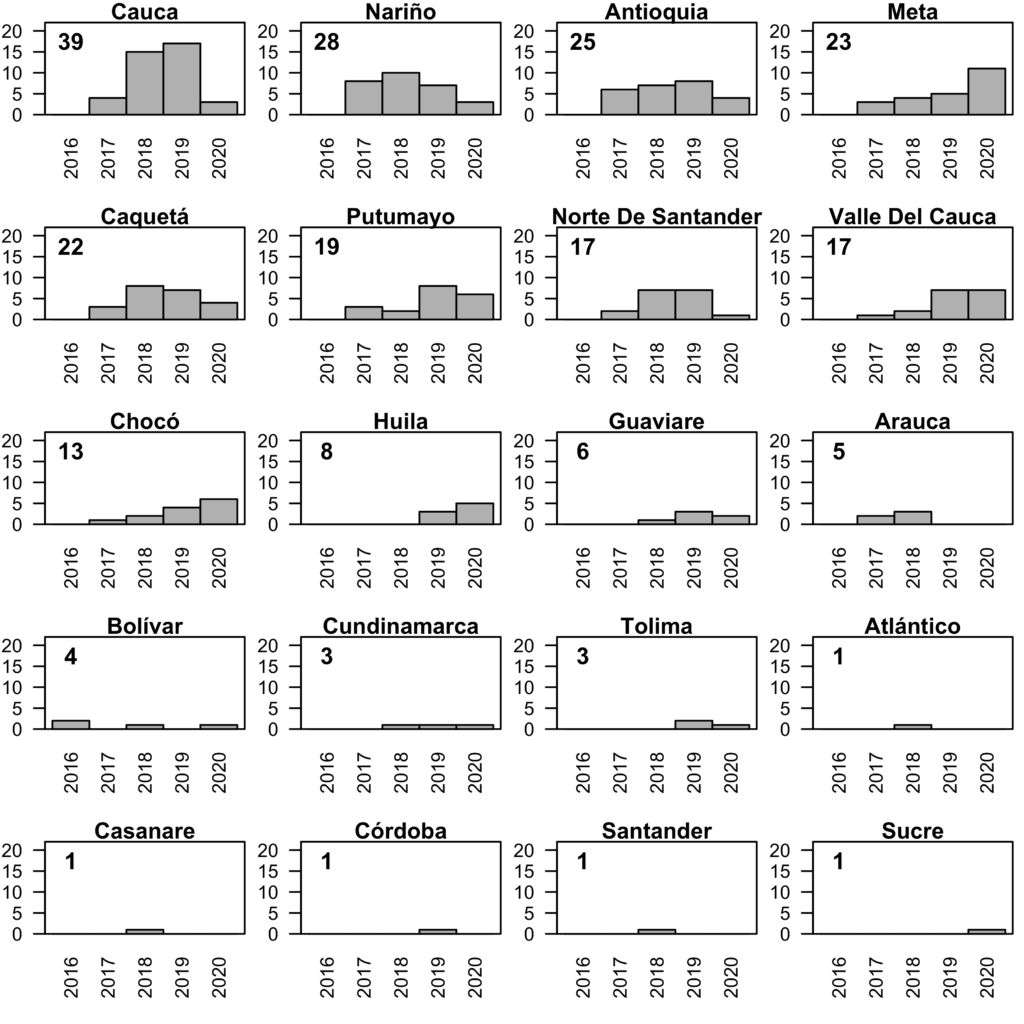

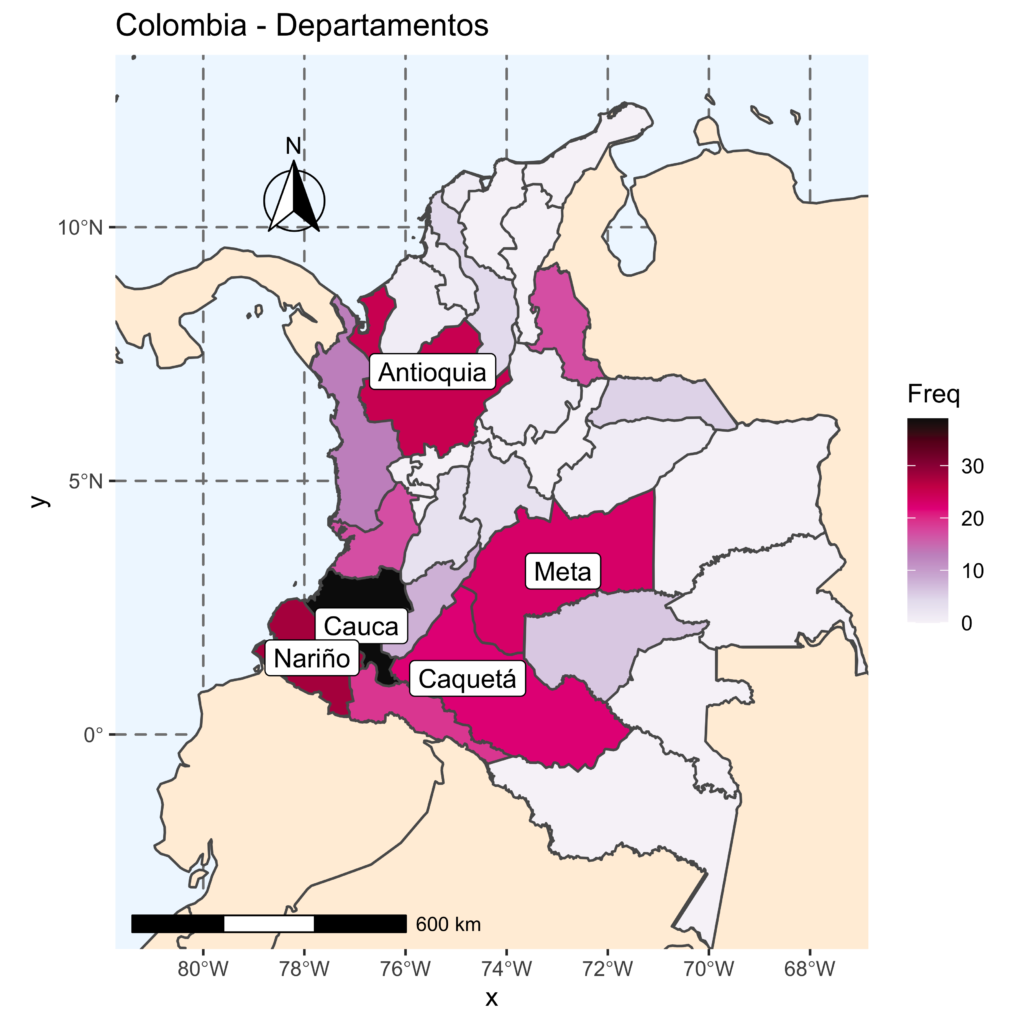

Using lists compiled by the FARC and INDEPAZ, we have gathered data on 241 victims. Important and interesting trends emerge. The data visualizations below show the distribution of killings disaggregated by year and department. The killings are concentrated in specific departments; 137 or 55 percent of the killings have occurred in just five of Colombia’s 32 departments: Cauca, Nariño, Antioquia, Meta, and Caquetá. In 2017, most of the killings took place in Nariño. In 2018 and 2019, it shifted to Cauca, and this year most of the killings have occurred in Meta.

Some might assume these patterns are related to drug trafficking, but according to the Investigation and Accusation Unit (UIA), “in 63% of the coca-growing territories there are no homicides against ex-combatants.” In fact, most of the killings occur in and around the Territorial Training and Reincorporation Spaces (ETCR), now called Old Territorial Training and Reincorporation Spaces (AETCR) where about half of the over 13,000 demobilized FARC settled following the peace agreement. Indeed, the five departments where a majority of the killings have taken place are also where 14 of the 24 AETCRs (58 percent) are located.

Threats of violence take a toll on residents. In fact, all but 2,610 individuals, or less than 30 percent of those who originally settled in the ETCRs, have left. These individuals have opted either for individual reincorporation or have settled in one of 93 collectives known as New Reincorporation Areas, which are not officially recognized by the government and therefore are not eligible for benefits provided to formal reincorporation spaces.

In the worst cases, entire ETCRs have been relocated. For example, families living in the Santa Lucía ETRC in Ituango, Antioquia were relocated to Mutatá in July as a result of the increased killings and a lack of security. Complicating matters, issues of property rights remain one of the greatest obstacles to the successful reincorporation for the ex-combatants.

Most of the ex-combatants killed are men between the ages of 20 and 40; only 4 of the 241 victims have been women, despite making up about 40 percent of the FARC’s armed forces. While women face post-war stigma and violence, they are not killed with the same frequency as men.

The government itself is accused of involvement in the violence. Early in 2019, Colombian generals and colonels pledged to violently increase efforts using a quota system to “secure peace.” This is alarming because, prior to the end of the civil war, similar incentives led to false positives or the killing of at least 2,248 and as many as 5,000 innocent civilians disguised as combatants.

In a recent public hearing that lasted over eight hours on November 25, 2020, the Director of the Investigation and Accusation Unit of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, Giovanni Álvarez, warned that “the implementation of the Peace Agreement is at stake.” He elaborated, “One of the patterns indicates that there is a dismantling of political, economic or community projects linked to the implementation of the Peace Agreement in the territories, through the elimination of ex-combatants who assume leadership roles.”

In recently published research, Angela D. Nichols argues that “If the government continues to attempt to avoid acknowledgment of its own wrongdoings through official legislation, while also allowing the unofficial persecution of former guerrillas, tensions could reignite.” Indeed, since taking office, the Duque administration has actively attempted to limit and change some functions of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP)—the legal arm of the comprehensive transitional justice system and peace agreement—thereby threatening the legitimacy of not only the institutions but the entire peace process.

What should be done?

Rodrigo Londoño, known as Timochenko or simply Timo, a former military commander and current political leader of the FARC, has faced an assassination attempt and has called upon President Duque and the international community to do more to stop the killings. In a letter to former President Santos, Londoño called on the Havana Accords signatory and Nobel Laureate, as well as the international community, to recognize the FARC’s efforts to comply with the peace accord and acknowledge the lack of compliance, and perhaps even undermining, of the peace agreement by the Duque administration.

Demands for action culminated in November when over 2,000 ex-guerrillas gathered in Bogotá following a pilgrimage from Meta to demand that the killings of the ex-combatants end and the government fully comply with the peace agreement. In response to the pilgrimage, President Duque met with FARC representatives to discuss the killings and what might be done to stop them. But the Democratic Center—the President’s party—is concurrently promoting a referendum to repeal the JEP.

One FARC ex-combatant shared the gravity of the situation in a conversation with one of the authors. “We see a new conflict coming, and we don’t want [history] to be repeated. We need the world and the international community to help us.” This individual used to be full of energy and excitement for peace, but is less and less hopeful as the security situation deteriorates. She did not previously fear violence in and around her ETCR, which was a former FARC stronghold, but now laments the lack of security.

In order to stop the killings, the Colombian government needs to consider several policies. First and most urgently, they should identify the perpetrators and those responsible for ordering the killings, and end policies that incentivize killing. While 33 arrests have been made, there is still a great deal of uncertainty and disagreement regarding the systematic nature of these killings.

Second, delays in security details and a backlog of requests leave many individual FARC ex-combatants threatened and vulnerable. The UN envoy for Colombia recommends that more resources be devoted to the National Protection Unit to increase security for individuals.

Third, New Reincorporation Areas (NARs) need security when requested. While the NARs are not officially recognized by the government, security threats in these spaces are legitimate, just like those that occur in and around AETCRs, which sometimes also need additional protection.

Overall, the international community—governments, non-governmental organizations, and individuals involved in overseeing the implementation of the peace process—should consider recommendations that emphasize policies that protect the remaining FARC ex-combatants in addition to policies designed to ensure general compliance with the peace agreement.

Angela D. Nichols is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Florida Atlantic University. Christopher J. Fariss is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and Faculty Associate in the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan. The authors would like to offer special thanks to Miguel Amaya and Dario for research assistance and translation.