Guest post by Britt Koehnlein and Ore Koren

The question of whether the COVID-19 pandemic caused a spike in insurgent violence received international attention from researchers and the media. But observers have largely ignored the pandemic’s effects on another set of fighters: pro-government nonstate actors (PGNs).

With rebel groups waging deadly civil wars in Yemen, Afghanistan, and Nigeria, to name a few, the interest in whether their attacks may become even deadlier makes sense. Researchers are divided though on whether COVID-19 has led to an intensification in rebel attacks, with some identifying increases in insurgent violence due to the pandemic and others finding no such evidence. In a recent paper, we analyzed the global impacts of the pandemic on the activity of both rebels and pro-government nonstate actors during the first six months of 2020. We didn’t find a clear relationship between COVID-19 and rebel violence, but we did find strong evidence that violence by pro-government groups—such as militias, paramilitaries, and mercenaries—has increased since COVID-19 began spreading, compared with 2019 levels.

Why?

Even before the pandemic, many of the PGNs we studied were already well-positioned to exploit opportunities to consolidate power. Pro-government groups play a crucial role in many civil conflicts. States with limited resources often rely on them to supplement official military forces, endowing them with varying degrees of power and authority, especially in remote places where the military has little to no presence. But PGNs often have interests of their own, which can create a complicated relationship between them and the government, especially if the PGN is unregulated and not fully loyal to the regime. These groups also have staying power, given their often local contacts and ability to fight in less conventional ways, which can lead these groups to try to exploit opportunities to increase their local and national impact.

One such opportunity is a pandemic. Epidemics and pandemics strain the administrative capacities of weak states. When an epidemic breaks out, these countries must shift resources to mitigate and combat the disease, which leaves populations vulnerable to rebel attacks and creates space for heightened PGN activity. PGNs are often not as densely contained or as large as official militaries, so they are inherently less susceptible to the adverse consequences of fast-spreading diseases like COVID-19. As a result, PGNs can exploit disease-driven power vacuums to seize control of certain areas, thereby illustrating their position as a key ally of the government—or as a viable alternative. In Iraq, for example, COVID-19 has undermined “the fledgling government’s legitimacy, as militias have stepped in to supply medical and humanitarian services,” according to a report by the Council on Foreign Relations.

Rebels can also exploit the power vacuum created by the pandemic, but PGNs have an advantage. They can directly react to the government’s retraction, serving as immediate substitutes for the formal state and engaging in combat to protect pro-government enclaves from rebels. They can also engage in attacks preemptively to quash any potential for rebels to gain territory. In doing so, PGNs are able not only to weaken the rebels, but also to establish themselves as an invaluable ally of the state, thereby increasing potential revenues and resource support from the latter.

The conflict in Nigeria is a great example of these dynamics. The government of Nigeria often relies on PGNs, because of their low cost and willingness to use extreme tactics, to fight Boko Haram, a violent insurgent group. As COVID-19 began spreading, Boko Haram saw an opportunity, stating that “the virus and subsequent economic downturn would divert government attention, weaken capacity and increase fragility, giving its fighters more inroads.” Yet, as the government began to shift its focus from countering Boko Haram to providing pandemic relief, several PGNs began to launch what appears to be preemptive offensives against the group.

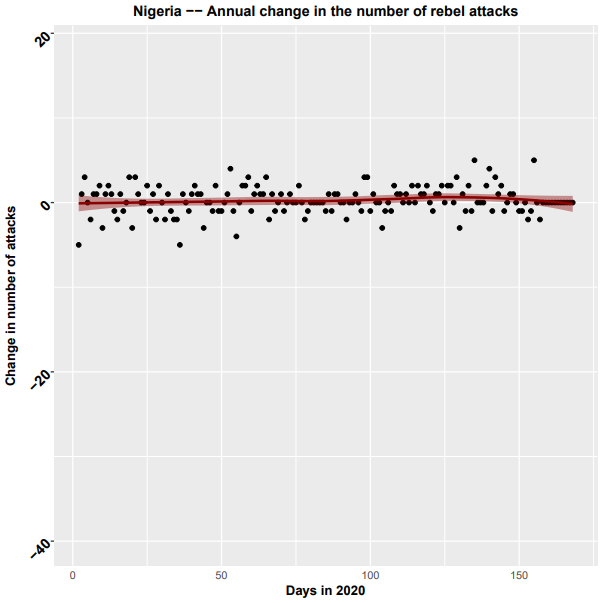

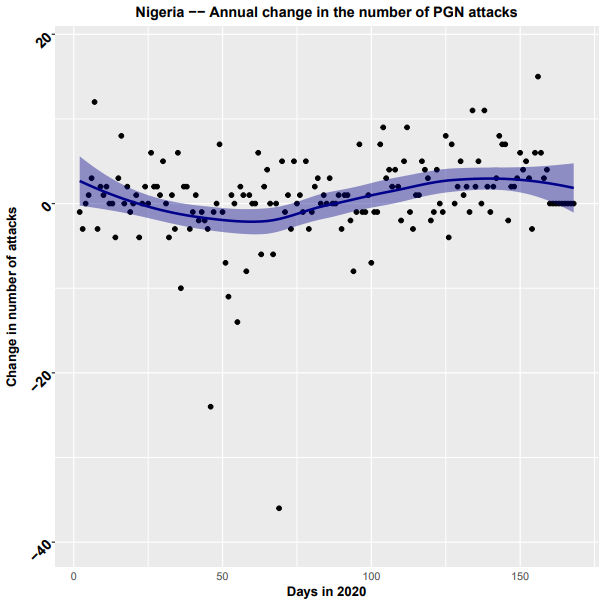

Using data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED) to compare the number of rebel versus PGN attacks in Nigeria in 2020 and 2019, we found that the number of rebel attacks in the first half of 2020 remained relatively unchanged compared with the same period in 2019, although there was a slight intensification as the number of COVID-19 cases increased in the spring (see figure). In contrast, the number of attacks by PGNs in 2020 gradually increased compared with 2019 levels—and the rise preceded the peak in rebel attacks. What this suggests is that the rise in PGN attacks may have occurred preemptively, which helped stave off rebel attacks. Our comparative global analysis shows that this dynamic also occurs in other countries.

This should be cause for concern for those states involved in civil conflict that must also mitigate a pandemic. Though resource-constrained states may rely on PGNs, given resources and discretion, PGNs may instigate rather than prevent violence, putting both political stability and civilians at an increased risk.

This is especially concerning considering pandemics can open the door to severe government overreach. In addition to creating space for PGNs to pursue their own goals, unscrupulous leaders may actively use PGNs to target their opposition while enjoying plausible deniability. Aligning goals between leaders seeking to stay in power and PGNs who want to increase their influence is another way the pandemic can reinforce growing global illiberal trends and fuel right-wing populism.

Britt Koehnlein is a graduate student at Indiana University Bloomington and Ore Koren is an assistant professor of political science, also at Indiana University Bloomington.