Guest post by Meghan Garrity

January 30, 2023 marks 100 years since the signing of the Lausanne Convention—a treaty codifying the compulsory “population exchange” between Greece and Turkey. An estimated 1.5 million people were forcibly expelled from their homes: over one million Greek Orthodox Christians from the Ottoman Empire and 500,000 Muslims from Greece.

This population exchange was not the first such agreement, but it was the first compulsory exchange. Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion and Muslim Greek nationals did not have the option to remain. Further, Greek and Muslim refugees who had fled the Ottoman Empire and Greece, respectively, were not allowed to return to their homes. Only small populations in Istanbul and Western Thrace were exempted from the treaty.

The population exchange between Greece and Turkey is an example of the broader phenomenon of mass expulsion—a government policy to systematically remove an ethnic group without individual legal review and with no recognition of the right to return. Far from an isolated incident, the Lausanne Convention was one of 19 population “transfers” or “exchanges” throughout Europe in the early twentieth century. These expulsions occurred with the stroke of a pen, but mass expulsions also occur at the point of a sword. Governments use violence to force out “undesirable” groups by destroying their homes, appropriating their assets and income, and in some cases, killing members of the group to encourage others to flee.

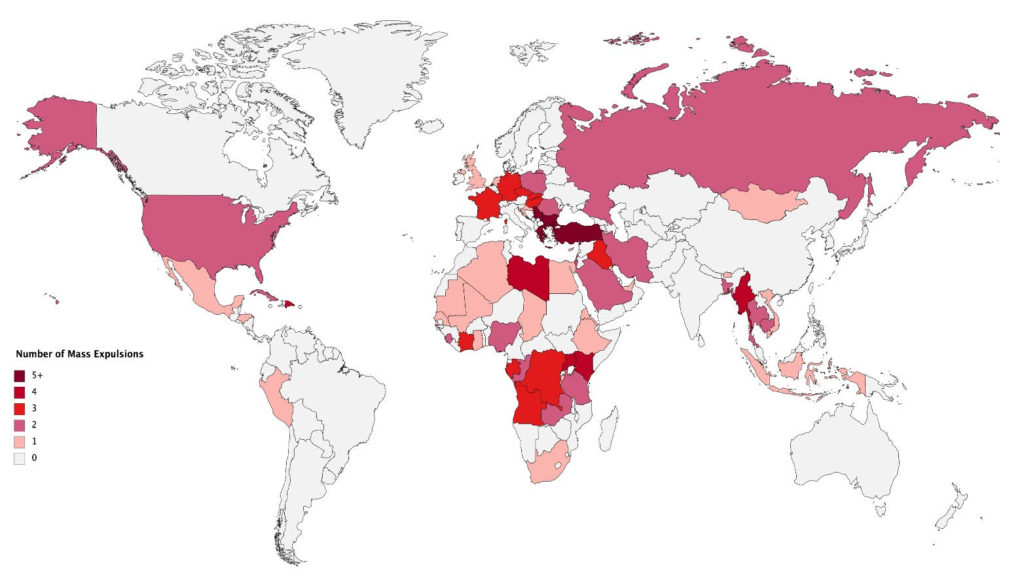

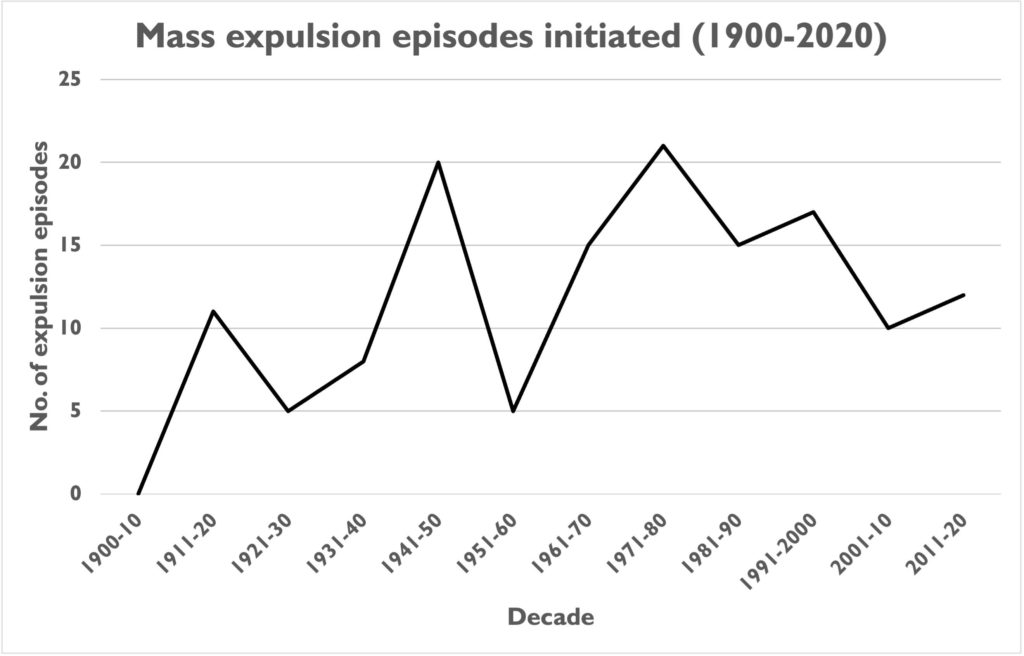

Although mass expulsion is rare, it is recurring. Between 1900–2020, governments expelled over 30 million citizens and non-citizens in 139 different episodes around the world.

Far from a historical phenomenon, over the last 50 years governments have continued to implement expulsion policies at an average rate of 1.56 per year. In just the last two decades (from 2000–2020) there were 24 expulsion events, including Eritreans from Ethiopia (1998–99); Rohingya from Myanmar (2012–13; 2016–18); and Afghans from Pakistan (2016).

What explains this recurrence? In the early decades of the twentieth century, particularly after World War I, minority groups were seen as dangerous Trojan horses that sowed instability and brought insecurity. The “Great Powers” and international institutions like the League of Nations, promoted expulsion as a necessary policy to “unmix” antagonistic populations. It was believed that only by reuniting groups with their co-ethnics and establishing homogenous nation-states—however fanciful that idea was in practice—could international peace and security be achieved.

Therefore, in post-conflict environments mass expulsion was often considered a viable policy, typically disguised in the more benign-sounding language of population “transfer” or “exchange.” The 1923 Lausanne Convention was part of one such post-conflict peace agreement that ended the war between Greece and Turkey and redrew the borders of the soon-to-be Turkish Republic.

Notable figures such as British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US President Herbert Hoover openly promoted and lobbied for mass expulsion. In 1942, in the midst of World War II, Czechoslovakia President-in-exile Edvard Beneš wrote in Foreign Affairs, “It will be necessary after this war to carry out a transfer of populations on a very much larger scale than after the last war. This must be done in as humane a manner as possible, internationally organized and internationally financed.” After the war, the Allied Powers carried out Beneš’ wish. The 1945 Potsdam Agreement authorized the “orderly and humane” expulsion of between nine and 12 million ethnic Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary.

But international norms and law slowly began to shift. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights included the right of nationals to return to their country of origin. The next year the Fourth Geneva Convention prohibited “individual or mass forcible transfers.” Protection for refugees soon followed with the 1951 Refugee Convention explicitly stating, “No contracting state shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee.” Subsequent regional human rights treaties bolstered legal frameworks against the expulsion of both nationals and non-nationals, including the European Convention on Human Rights, Protocol 4 (1963), American Convention on Human Rights (1969), African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981), and more recently the Arab Charter on Human Rights (2004). In 1998 the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court included “deportation or forcible transfer of populations” as Crimes Against Humanity.

Yet despite these legal advancements, mass expulsion persists. Although laws against expulsion are in place, there is minimal, if any, regional or international enforcement. In the face of myriad atrocities and human rights abuses, cases of mass expulsion are not prioritized. The limited international justice resources are dedicated to accountability for more heinous atrocities like genocide. Unfortunately, multiple rounds of mass expulsion may eventually escalate to more serious violence as in the case of the Rohingya in Myanmar: expelled in 1978, 1991–92, 2012–13, and 2016–18. Only this latest episode has been referred to the International Court of Justice amidst accusations of genocide.

Governments also hesitate to call out others for implementing expulsion policies because they too have expelled. In 1983 Nigeria expelled over two million West African migrants without any serious criticism from its regional neighbors. Affected countries like Ghana, Niger, and Chad had previously expelled populations from their territories, and thus refrained from condemning Nigeria.

Furthermore, while mass expulsion has continued over time, the nature of the person targeted has changed. In the first half of the twentieth century, mass expulsions almost exclusively targeted citizens. Since 1950, only 12 incidents of citizen-only expulsions have occurred, which at first glance seems to indicate the customary international law against expelling citizens has diffused around the world. But, on the contrary, expelling states have simply modified their strategy by removing citizens simultaneously with non-citizens—foreign nationals, resident aliens, and/or refugees. When non-citizens are the main target of expulsion, these decisions are often considered “immigration policies” under the sovereign jurisdiction of the state. However, international law also guarantees the protection of non-nationals from mass expulsion and requires certain rules to be followed, including non-discrimination and individual legal review. The en masse removal of groups based on identity characteristics is illegal.

Mass expulsion, in whatever form it takes, has gross humanitarian consequences for those affected. In the chaos families are separated, homes and livelihoods are left behind, and in some cases, lives are lost. Importantly, research shows these policies do not bring the positive outcomes their advocates proclaim, and expelling states often suffer economically and politically in their aftermath.

The anniversary of the 1923 Lausanne Convention is a moment to reflect on the tragedy of the Greek-Turkish “population exchange.” More policy attention is needed to prevent and punish mass expulsion.

Meghan Garrity is a postdoctoral fellow in the International Security Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School.