By Etain Tannam for Denver Dialogues.

The Brexit referendum to leave the EU created one of the biggest crises in Europe since World War II, and in Ireland since the foundation of the state. In Northern Ireland, a majority (55.7% of voters and 85% of Catholics) voted to remain in the EU. For Irish civil servants and politicians, fresh from coping with the EU bailout and austerity, Brexit is an immense economic and political challenge.

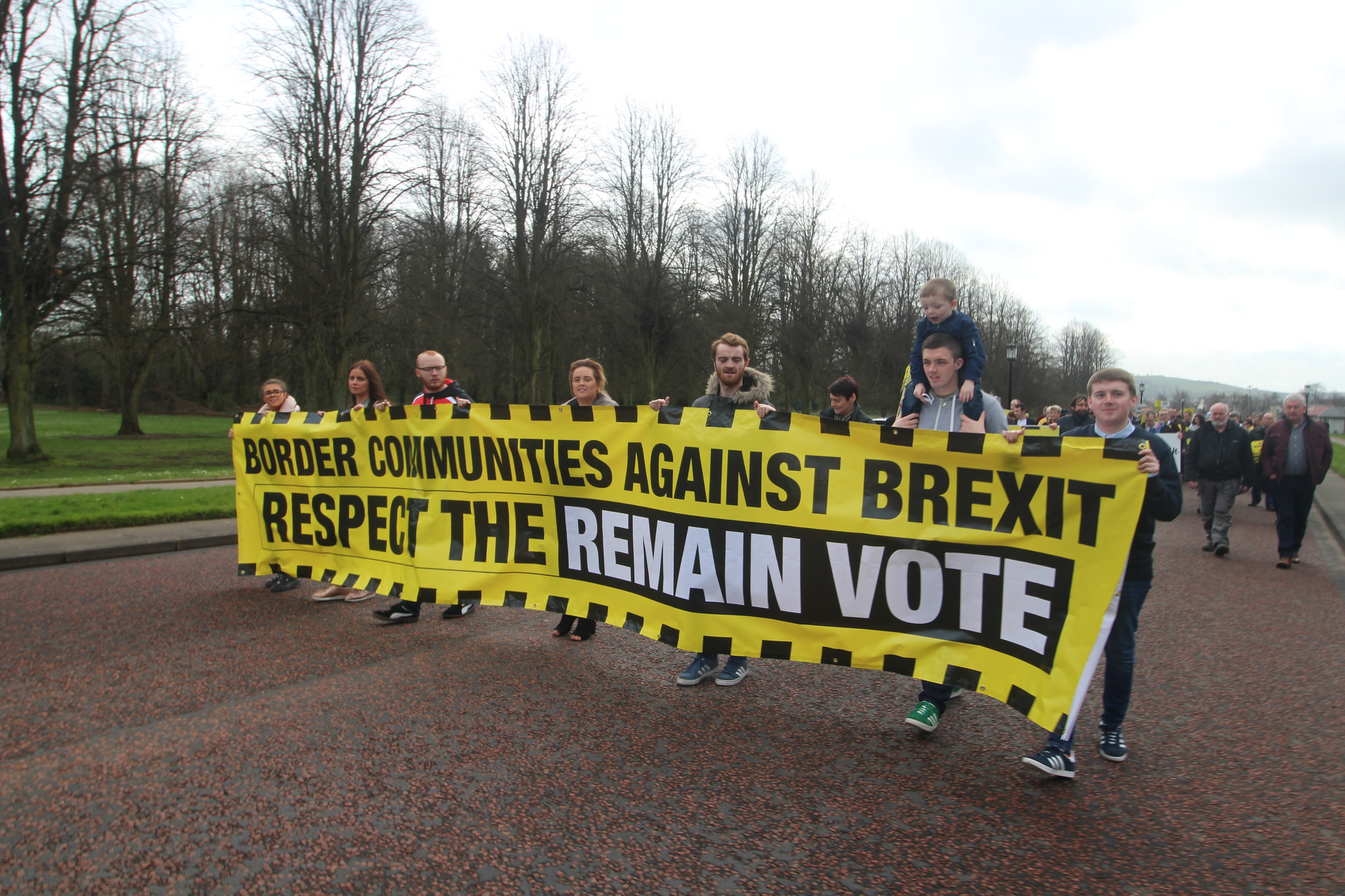

First, although Irish trade has diversified considerably since UK and Irish membership to the EU in 1974, 41% of Irish agri-food exports still go to the UK; in turn, Ireland is the UK’s fifth biggest export market. A “hard” Brexit – whereby the UK leaves the EU Customs Union – implies that trade revenue and economic growth will be badly damaged. Secondly, although in absolute terms cross-border trade is small between Northern Ireland and Ireland, communities living on either side of the Irish border are highly dependent on local trade. In addition, the EU has provided substantial amounts of financial aid to these communities through EU regional funding and its Peace packages (since 1994).

Second, Brexit portends a number of political challenges. The EU created a neutral framework for Northern Irish unionist and nationalist politicians to lobby jointly for common interests, such as agricultural funding and EU funding, despite their ideological differences. Thus, the EU is credited with contributing to the peace process and it is explicitly mentioned in Strand 2 of the Good Friday Agreement that brought peace to Northern Ireland. Tony Blair, former UK Prime Minister and one of the chief negotiators of the GFA, has argued recently that the GFA will have to be amended following Brexit.

Third, there is an additional diplomatic problem for the Irish government in that, in most areas, its policy preferences in the EU have been closely aligned to those of the UK. As such, a hard Brexit implies that Ireland will lose a key bargaining ally while, at the same time, it must be careful to support its EU partners and not be seen to take sides with the UK in its Exit negotiations. Domestically, the Fine Gael-led Irish government is also attempting a balancing act in stemming any surge of support for nationalist Sinn Fein. Indeed, immediately after the June 2016 Brexit result, Sinn Fein called for a ‘border poll’ on Irish unity and Fianna Fail followed suit soon after.

Last, but not least, are the negative implications of Brexit for peace in Northern Ireland. The rise of the Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) and Scotland’s vote to remain in the EU could increase nationalist demands in Northern Ireland for a united Ireland. Brexit, by mobilizing calls for a border poll, creates instability in Northern Ireland and adds to insecurity among unionists – in short, Brexit could potentially reverse much of the progress of past decades.

Thankfully, however, there are some caveats to such a bleak scenario. Irish governmental lobbying efforts over the past year have, for instance, contributed to the EU’s decision to list Ireland and Northern Ireland among its top three bargaining priorities. Moreover, in a recent address to the Dail Eireann (the Irish parliament), Michel Barnier, the European Commission’s lead Brexit negotiator, stated that Ireland had the EU’s full support.

It is also important to note that the British–Irish relationship is far stronger and much more institutionalized now than it was in the 1970s. British and Irish officials have met frequently to discuss Brexit’s impact and UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, prioritized Northern Ireland in her 12-point Brexit plan in December 2016. The hope is that, regardless of the outcomes of Brexit, the move should not dramatically damage British-Irish relations if both governments continue to prioritize its importance.

The above caveats create a slightly brighter picture of Brexit’s implications for both Ireland and Northern Ireland. The key issue, however, is that Brexit has unknown and unintended consequences. Whether a customs union will be agreed upon is unknown – and many say it is quite unlikely – given the hardline start to the negotiations since Article 50 was triggered in March. Furthermore, whether the UK government, faced with complex and multiple EU bargaining issues, will continue to prioritize Northern Ireland and British-Irish relations remains a question mark. In sum, the EU is very aware of Ireland and Northern Ireland’s situation and is likely to make an exception for them in the final bargaining outcome. That said, the political and economic uncertainty created by Brexit presents the possibility for a harmful slippage in British-Irish relations as Brexit negotiations forge ahead in the coming months.

Etain Tannam is an Assistant Professor of International Peace Studies at Trinity College Dublin.