Guest post by Sebastian van Baalen and Jesper Bjarnesen

Ivorians head to the polls on October 31, in Côte d’Ivoire’s most momentous election since the post-election crisis that caused 3,000 deaths in 2010–2011. The pre-election period has seen low-intensity violence like riots, violence against protestors, and sporadic communal violence. Many Ivorians fear the elections will spark an escalation of violence, as did the presidential elections before the first (2002) and second (2011) Ivorian civil war.

Here are seven factors that increase the risk of violence in Côte d’Ivoire—and how to counter them.

1. The presidential contest could become highly competitive

The 2020 presidential election pits two-term incumbent Alassane Ouattara against former president Henri Konan Bédié, and long-term opposition leader Affi Pascal N’Guessan. With Bédié and N’Guessan positioned to form a coalition to defeat Ouattara, there are signs that this year’s contest will be tight. This is troubling because research demonstrates that the risk of electoral violence is greater when the incumbent faces uncertainty at the polls and the electoral contest is more competitive.

2. The incumbent is running for a third term

The 2020 election’s biggest controversy is Alassane Ouattara’s bid for a third term. The opposition claims that Ouattara’s third-term bid is unconstitutional, but the incumbent argues that constitutional amendments in 2016 reset the term count. Ouattara’s third term bid is of grave concern to political stability in Côte d’Ivoire. Electoral violence is more likely in elections where an incumbent presidential candidate is running for re-election, and third-term controversies have caused electoral violence in several recent African elections, including in Burundi, the DRC, and Guinea. Moreover, an Ouattara victory could spark further protests, as 78 percent of Ivorians believe that the constitution should set a two-term presidential limit.

3. There are serious concerns about electoral integrity

Both internal and external observers have raised concerns about the composition and conduct of the Ivorian electoral commission. The African Court on Human and People’s Rights recently argued that the electoral commission’s nomination process did not allow the opposition and civil society enough say in choosing their nominees. Other concerns include irregularities in the voter registration process and constitutional amendments that benefit the incumbent. The Ouattara government has also faced criticism of its conduct towards the political opposition, including the alleged harassment and arrest of opposition politicians and imprisonment (in absentia) of two challengers. The compromised electoral integrity heightens the risk of unrest, as accusations of fraud can help the opposition mobilize people in the event of a close race.

4. The candidates are mobilizing ethnic support bases

Côte d’Ivoire’s political parties are still predominantly organized around ethno-regional groupings. This is bad news, as salient ethnic cleavages significantly raise the risk of electoral violence. Electoral violence in Côte d’Ivoire in 2010–2011, for example, was most intense in areas of significant ethnic polarization.

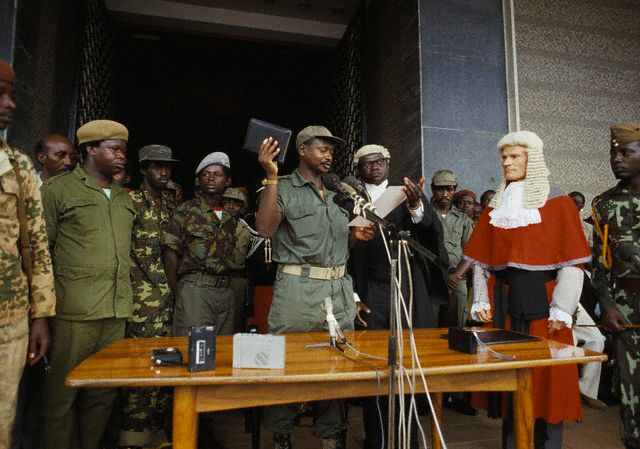

5. The armed forces are deeply divided

The integration of former rebels and enduring factional loyalties have left the Ivorian armed forces deeply divided. More than 50 military uprisings have occurred over the course of Ouattara’s presidency. President Ouattara has been somewhat successful in co-opting the infamous former mid-level commanders of the Forces Nouvelles rebellion. However, there are still concerns that these powerful commanders remain loyal to former rebel leader Guillaume Soro, currently exiled in France. In the event the election triggers demonstrations and riots, the armed forces may lack the civilian oversight and cohesion to act as a protector of the people.

6. Land conflict continues to be prevalent

Land ownership is one of the most complicated and politicized issues in Côte d’Ivoire. The civil wars of 2002–2011 were driven in part by land ownership issues, and little has been done to address the underlying problems. Land conflicts still turn violent in Côte d’Ivoire, often causing massive displacement. A land conflict in the Cavally region in 2017, for instance, left seven people dead and 5,000 displaced. This is deeply unsettling because the prevalence of land conflicts has been found to increase the risk of electoral violence, and has been a source of electoral violence in Côte d’Ivoire in the past.

7. Ivorian politics are neo-patrimonial in character

Access to public employment and business opportunities in Côte d’Ivoire is usually given to the winning side, leaving the losing side politically and economically marginalized. In a country with pervasive economic inequality, this neo-patrimonial doling out of rewards to those loyal to the political winner raises the stakes of elections and reinforces a winner-take-all scenario. Moreover, clientelist networks are often related to electoral violence, as they enable politicians to mobilize their dependents.

Averting Violence

Though tensions continue to rise in anticipation of the 2020 elections, Afrobarometer survey data suggest that 77 percent of Ivorians agree that democracy is the preferable form of government. Our field research also suggests that most people do not want a return to armed conflict. Moreover, Côte d’Ivoire has several restraint mechanisms, which may serve to moderate violence: a long history of inter-ethnic and religious dialogue; a comparatively large middle class; and a vast agricultural export economy that incentivizes moderation. Moreover, the still-fresh memories of post-electoral violence in 2010–2011 may encourage communities to pull back from the brink.

What can the international community do to prevent another electoral crisis in Côte d’Ivoire? Three points stand out. First, the international community should ensure transparency of the electoral process, including current and future complaints by the political parties. Second, multilateral organizations like the African Union, European Union, and the Economic Community of West African States, as well as France, should continue to put diplomatic pressure on all main candidates to refrain from polarizing tactics. This will be of particular importance before a potential second round, or if the elections are postponed, as both outcomes are likely to heighten tensions to dangerous levels. Third, election monitors should closely monitor land conflicts and communal conflicts between host and immigrant communities, before, during, and after the elections.

Sebastian van Baalen is a PhD candidate at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University. Jesper Bjarnesen is a senior research at the Nordic Africa Institute, Uppsala.