In a forthcoming American Political Science Review article, Chris Fariss reports that:

The standard of accountability used [by human rights monitors] to assess state behaviors becomes more stringent as monitors look harder for abuse, look in more places for abuse, and classify more acts as abuse.

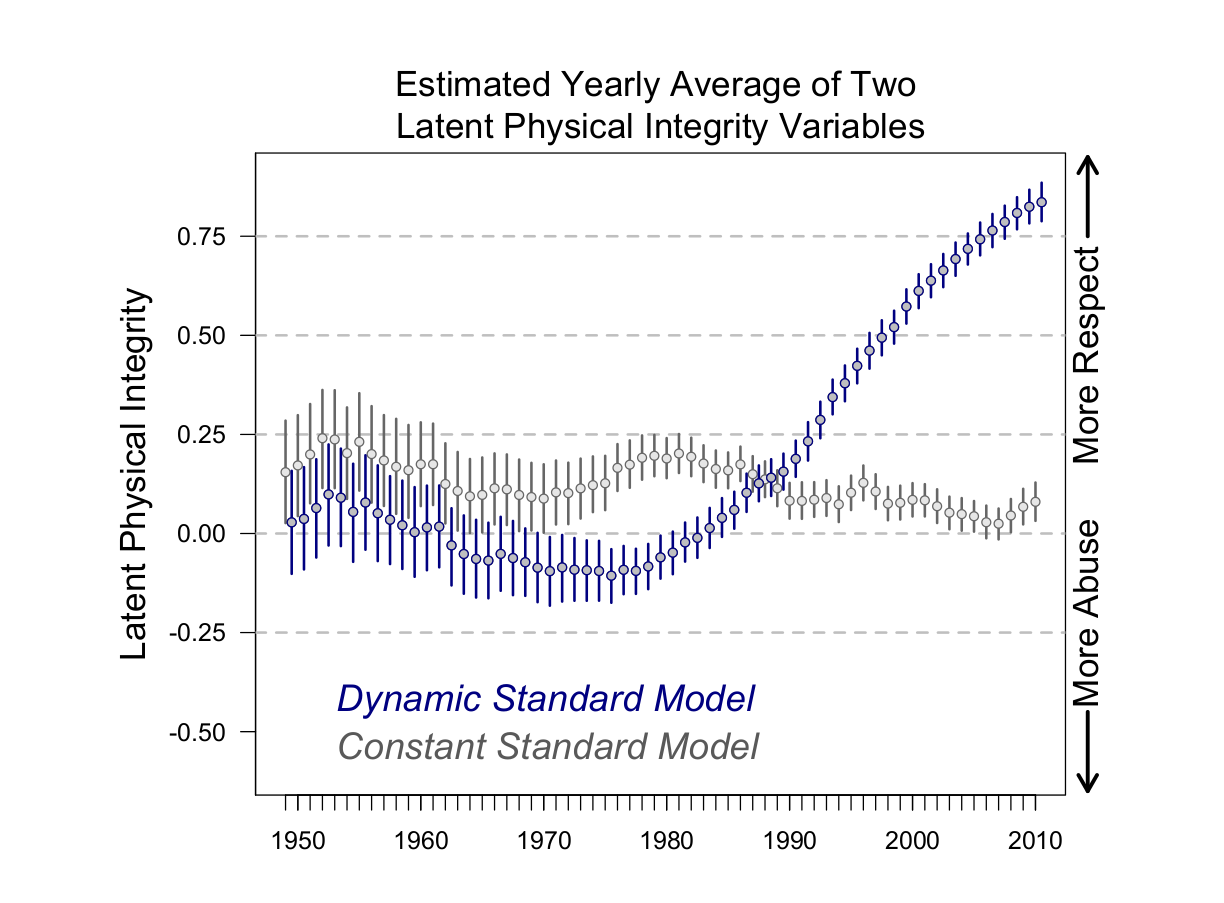

That is, Fariss, who employs sophisticated statistical models to reach his conclusion, finds considerable evidence to suggest that since 1980 governments’ respect for physical integrity rights[1] has improved globally. More precisely, in response to pressure, governments have limited the most egregious forms of abuse, and in response human rights monitors have shifted to calling governments out for less egregious, but equally illegal forms of abuse. The figure below, from the paper, depicts the trend graphically.

Compare this with Amnesty International’s recent allegations as it launched a Stop Torture campaign.[2]

“Governments around the world are two-faced on torture – prohibiting it in law, but facilitating it in practice” said Salil Shetty, Amnesty International’s Secretary General, as he launched Stop Torture, Amnesty International’s latest global campaign to combat widespread torture and other ill-treatment in the modern world.

Torture is not just alive and well – it is flourishing in many parts of the world. As more governments seek to justify torture in the name of national security, the steady progress made in this field over the last thirty years is being eroded.”

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this new campaign in a survey of public attitudes in 31 countries. They ask three questions:

- If I were taken into custody by the authorities in my country, I am confident I would be safe.

- Clear rules against torture are crucial because any use of torture is immoral and will weaken international human rights.

- Torture is sometimes necessary and acceptable to gain information that may protect the public.

You can access a summary of the survey findings, Attitudes to Torture: Stop Torture Global Survey, here. RT.com (TV-Novosti) ran its coverage under the headline “Western Glorification of Torture Making it ‘Acceptable’ – Amnesty.” HufPo UK leads their coverage this way:

More people in Britain believe torture is acceptable than in Russia – partly thanks to popular TV shows such as 24, Homeland and Spooks, human rights campaigners have said.

Nearly one in three people – 29% – in the UK thinks torture is sometimes necessary and acceptable to protect the public, compared to 25% in Russia, according to a new poll conducted by Amnesty International.

The RT.com article casts an eye toward the US public:

The subject of torture suddenly entered America’s living rooms in the summer of 2003 as the ‘war on terror’ was really heating up. Amnesty reported the horrific details of torture in US-run Iraqi prisons, most notably in Abu Ghraib where reports, backed up by shocking photographs, showed Iraqi detainees being exposed to various forms of physical and mental torture. Unlike a disease that may be eradicated with the right diagnosis and medication, stopping the scourge of torture requires a fundamental change in the mentality of people, many of whom see the use of the age-old technique as ‘routine’.

“It’s almost become normalized, it’s become routine,” Amnesty secretary general Salil Shetty told a press conference at the start of the ‘Stop Torture’ campaign in London. “Since the so-called War against Terrorism, the use of torture, particularly in the United States and their sphere of influence… has got so much more normalized as part of national security expectations.”

Can one square the circle across the findings of Fariss and Amnesty International? One possibility, of course, is that the improved respect reported by Fariss has been in physical integrity rights other than freedom from torture.[3] Current evidence does not permit us to rule that out.

But we can do a cursory, and not scientifically sound, comparison of the AI public opinion findings to the survey findings of 31 countries in 2006 and 2008 studied by Peter Miller.[4] Like AI’s, these surveys document considerable variation across countries. 18 countries appear in both, allowing some rough comparisons across the past 6-8 years.[5]

The value rises in 11 of the 18 countries, and the correlation between the values is moderately positive (0.54). This is broadly consistent with Amnesty’s argument that, globally, public attitudes toward torture have become more lax. Having said, let me underscore the limitation of comparing across these surveys: “broadly consistent” is a far cry from “demonstrates” or “proves.”

The international human rights regime was constructed without the assistance of social science: activists and legal scholars raised it up and made it a reality. However, social scientists are really making some progress toward understanding what it takes to constrain Leviathan (PDF). Amanda Murdie recently provided a brief tour of recent research on human rights. You should check it out.

I anticipate increasing interaction and cross-fertilization between social scientists and monitoring organizations like Amnesty, as well as IGO and even national governments. Work like Fariss’ forthcoming article opens new avenues for scientific inquiry and debate, while reports like Amnesty’s highlight the need for vigilance and improved monitoring. As American abolitionist Theodore Parker argued, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” and while we have many rivers to cross, activists and social scientists each have much to contribute.

@WilHMoo

[1] The rights to the physical integrity of the person include the right to life, freedom from torture and other abuse that maims the body, detention without due process, and ill treatment during incarceration, among others. [2] You can access the report, Torture in 2014: 30 Years of Broken Promises, here. [3] That would be consistent, for example, with Darius Rejali’s work documenting a global shift, led by democracies, away from torture that leaves scars on the body toward torture that does not leave scars. [4] Miller, “Torture Approval in Comparative Perspective,” Hum Rights Rev (2011) 12:441–463 (open access). [5] The comparisons are not scientifically sound because the questions asked are not the same, nor is it clear how valid the sampling frames are, etc.

2 comments

If I understand the article, it is suggesting that the more people look for abuse, the more they find. I would imagine that this would be the case without needing a full study to confirm the well known idea “You find what you are looking for”. If you look for bad news, you find bad news. If you are looking for good news, you find good news.

At the same time, that the global community appears less tolerant of abuse may not even reflect the abuse but the political, economic, and social systems that prompt abuse. Many countries now realize that it is easier to coopt the opposition or simply pay them off, ie give everyone better living conditions so less to protest and thus less threat to the state, which reduces the need for repression or abuse and finally torture. Moreover, one could argue equally that social media makes torture, at least for extracting information rather than as simple punishment or demonstration of power, less of a necessity. You can find information about people electronically that previously would have required torture. At the same time, the victims can now link to others who have been tortured, create a memory to rival the state’s memory of the torture, and hold them to account, which was very hard 30 years ago or even 20 years ago. See for example,http://lawrenceserewicz.wordpress.com/2013/06/28/private-memories-public-accountability/

However, this still leaves us the problem of the United States. They rarely engaged in torture before 11 September 2001. We do not hear of its use, at least not publicly with WW2, Korea although it did start to emerge, on an adhoc basis, rather than systemically, in Vietnam. After that the wars were too short for torture to be a main issue and most militaries eschew torture although intelligence agencies, usually, are less squeamish about using it. Even then, the issue is the apparent necessity that drove the United States to act. The attack created the exception that justified the move from the normal. Yet, this is only at the national security level, where it is condoned.

what is missing is that lower level “torture” can be found ie police brutality or prison abuse can be seen as torture although this blurs into punishment and coercion rather than torture for a purpose ie military or intelligence.

The underlying issue, though, is that the state of exception still exists in the US and until AUMF (PL107-40) is repealed or revised, it remains. The problem, then, is not whether we are looking for it, it is the context has been been implicitly changed for it to be a necessity. Instead of worrying about glorification, look at the underlying changes in the regime and the political context that has been created by the change in the law.

Jim Pfiffner and I are editing a new book, Examining Torture: Empirical Studies of State Repression, with three chapters that look further into these questions. The chapter by Peter Miller, Darius Rejali, and Paul Gronke examines new survey data on torture approval through the years in the US that follows Rejali and Gronke’s earlier findings in more detail. Jeremy Mayer, Noaru Koizumi, and Ammar Malik present tests of hypotheses concerning the level of torture approval in 19 countries. Finally, and this may be most relevant to this post, Courtney Conrad and Jacqueline DeMeritt present good evidence that the attempts to shame regimes into abandoning torture lead to regimes shifting to greater use of other abuses of physical integrity rights as a substitute. (A pretty depressing finding, imho, but in line with what is reported here.)

I had one comment on Lawrence Serewicz’s post as well. He mentions “lower level torture … i.e. police brutality or prison abuse” as something that “… can be seen as torture although this blurs into punishment and coercion rather then torture for a purpose, i.e. military or intelligence.” I caution against making this distinction. The best way to think of torturous interrogations is to use Robert Conquest’s concept of a “long interrogation”. For example, is cursing at a prisoner torturous? It certainly can be if the prisoner is a devout Sunni Muslim who has been subjected to 20 hours a day of interrogations (and, remember, that four hours isn’t continuous; you wake the prisoner up as soon as he starts deep sleep and haul him off to be questioned) for 48 out of 54 days, along with being beaten and threatened and humiliated and subjected to hypothermia and strung up from the ceiling and short-shackled. (Btw, this is Mohammed al–Qahtani; I didn’t make this up.) Then you start cursing at him.

Out of context, the cursing is no more torture then urinating on him (yes, that too). As part of a long interrogation, however, it can be devastating. There’s a reason Solzhenitsyn included it in his list of NKVD torture techniques. That’s also the reason that the Geneva Convention doesn’t make a distinction between “cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment” and torture; the two are usually part of the same interrogatory process.