By Devin Finn for Denver Dialogues

After years of fraud and deception, a president falls. The narrative of prominent government figures’ distance from wrongdoing unravels, ensnaring him and the officials of his inner circle. The President, imprisoned and grasping for scapegoats, is disgraced, and ordinary people who have taken their demands to the streets are elated. Further allegations follow of the leader’s shadowy, silenced links to past atrocities and his mutual protection by fellow perpetrators of brutal violence. For citizens, the possibilities seem suddenly, dramatically, different—for justice, new leadership, and political change.

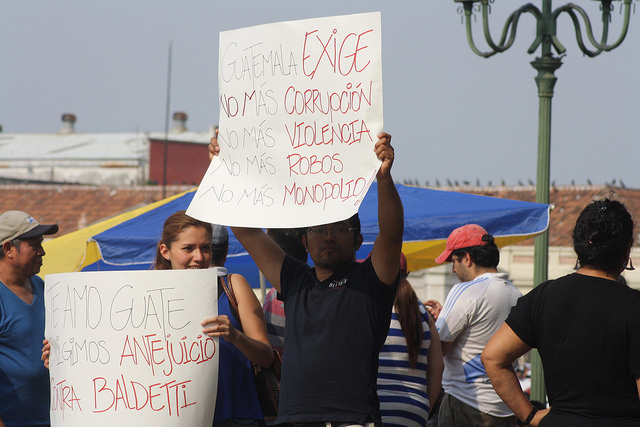

This scenario captures the last several months of political and protest activity in Guatemala. But it has emerged as a recognizable story in different contexts: abuse of power at the highest levels of government in countries with a history of extreme violence eventually, sometimes after many years, leads to a series of political and legal confrontations. The changes create the possibility of new roles for citizens in demanding accountability. Wide variation in “people power” in response to corruption and impunity has been occurring for decades, in places as diverse as Brazil, Egypt, and Korea. What do we know, as students of politics, about the empirical and theoretical connections between violence and corruption? Given that state and non-state actors who engage in corrupt practices are sometimes—though not always—the executors of violence, what can we say about when processes of violence and corruption co-vary and enable one another, and when do they diverge?

Michael Johnston defines corruption as “the abuse of public roles or resources or the use of illegitimate forms of political influence by public or private parties.” As Diego Gambetta argues, “corruption” describes a range of “social practices”: the social premises and effects of individuals’ behavior that engender or emerge from degradation in institutions. Studies suggest that people’s perceptions of corruption are important in many ways, including determining the political salience of corrupt acts and whether their incidence is seen as norm or exception. How people’s ideas about corruption are formed matters, but perhaps not in the ways that rankings and indices would lead us to believe. Can we separate our approximations of perceived corruption—often in index or ranking form—from the political and social conditions that make it possible for corruption to occur and flourish?

Corruption and Violence: It’s Complicated

In broad terms, we observe high levels of different kinds of violence in countries where corruption is common, including Kenya, Russia, India, Tajikistan, Honduras, South Africa, and Brazil, to name a few. Closer to home, Chicago comes to mind; a city where corruption in public education and homicides have reached shockingly elevated levels. Shaazka Beyerle provides evidence for the “corruption-poverty-violence nexus,” in which all bad things go together. Impunity for various kinds of criminality; state corruption; and violence practices often do co-vary. Guatemala’s Pérez Molina reaped the benefits of impunity for military abuses, of grand scale corruption, and of ties to shadowy criminal networks. In Nigeria, stolen public revenues, administered by “godfather” politicians, pay for the weapons and services behind political violence. Yet these dynamics may also diverge. Nigeria’s recently-elected president Muhammadu Buhari estimated that government officials had stolen one hundred and fifty billion dollars over the last ten years. Buhari has consistently positioned himself as a champion of clean governance. A former military dictator, in the past Buhari imprisoned activists and journalists in prosecuting a “war against indiscipline.” Now—benefitting from the considerable impunity that adheres to his past human rights violations—he has renounced repressive practices while standing firm against corruption.

But the purposes of violence deployed by actors who have access to corrupt practices or are embedded within a set of institutions in which corruption is routinely practiced vary widely. Sarah Chayes characterizes the Afghan government under Karzai as a “vertically integrated criminal organization,” a set of actors that was not, in fact, aiming to govern and failing, but rather directing its efforts to achieve other goals, like protection of subordinates and resource extraction. Corruption, was, in fact, driving the violence and insecurity that the United States and international actors were attempting to counter.

The link between violence and corruption is personified in Otto Pérez Molina, the former president of Guatemala who allegedly supervised the operation of La Línea, a tax-skimming scandal in which government actors received bribes from corporations in exchange for reducing the companies’ customs tax bills. Officials, including the ex-president, allegedly pocketed and divided the bribes. In 2011, Pérez Molina won the country’s presidential election on a promise to fight corruption and crime with a “mano dura” (strong-handed) approach. Guatemalans are very angry about La Línea: the consistently meager tax revenues collected by the state are a damning insult to citizens when hospitals lack the funds to remain open and basic medications are not available.

Pérez Molina, who resigned as chief executive on September 2, 2015 after losing his presidential immunity, is currently in Matamoros military prison in Guatemala City. The former general has been brought down by a political system which once was designed and structured – legally or illegally—to protect military commanders like him. But in the last several years, that system has gradually changed, and the UN-supported International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) has helped reform and equip crooked, broken judicial institutions. These changes in the justice system have not only resulted in important convictions, but allowed people to believe that justice is possible. Guatemala’s homicide rates have also declined in the last several years.

Pérez Molina is tied not only to wartime atrocities but also, allegedly, to the assassination of Bishop Juan Gerardi in 1998, two days after the release of the Catholic Church’s massive human rights report on violations and crimes committed during the country’s civil war (1960-1996). He is accused of involvement in the massacres of civilians in the Ixil town of Nebaj in 1982, the sort of command responsibility which resulted in a conviction of another former president-general for genocide.

These anti-impunity processes have implications beyond the borders of Guatemala. Reverberations are felt directly in Mexico, where possible collaboration among the historically corrupt ruling party, the PRI, the military, and local and national police pervades questions asked by relatives of the 43 disappeared Ayotzinapa students about what exactly happened to their sons and brothers. Setting aside the real estate scandals that plague Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto, the Ayotzinapa case brings to the fore the question of whether entrenched institutional impunity can be challenged and justice achieved in Mexico. Some family members of the 43 have asked for a “CICIG for Mexico,” which is unlikely, given party politics and the need for congressional approval of an internationally-backed body.

Guatemala’s recent strides also mean that other Central American countries like El Salvador and Honduras may grapple with governments’ roles in war crimes and human rights violations, as well as their involvement in corruption, money laundering, and drug trafficking.

Explaining variation in public responses to corruption also demands study. Civil society organizations are developing budget monitoring mechanisms, for instance, to hold institutions and individuals accountable for spending commitments. As Goldman noted about Guatemala, “the fact that people in the highest positions of power can be held accountable, it opens up serious possibilities.” Beyerle argues that people taking concerted action against state corruption has created political will for reform where it did not exist.

Finding evidence of corruption may constitute a task distinct from detecting its workings in society. This investigation is a political act in itself, and may be dangerous. The practice of corruption and its persistence takes forms detectable in the most mundane of daily exchanges. In Guatemala, ordinary people have clear memories of protestors being killed in the streets for any form of public, political action during the country’s long war. As an institution, the Guatemalan police has not been reformed since the conflict’s end; many individuals remain in the roles they occupied during the war. In the last few months, though, Guatemalans seem to have lost long-held fears of going out into the street, as Claudia Paz y Paz described. In the country’s history, the middle class, it is famously said, has never come out to protest—only the poorer classes. But their presence was undeniable in the first protest in April, attended by 32,000 people calling for the resignation of the Vice President for her role in La Línea. #ResignNow became #Ihavenopresident, which became #JusticeNow. Since then, the protestors have grown to many more tens of thousands, calling not only for resignations but permanent reforms.

2 comments

For a bit more historical reference from the perspective of the Mayan people whose lands were being stolen during the civil war there’s no better book than I, Rigoberta Menchu. And I would say that American involvement in destabilizing the region through asserting its capitalist geopolitical

oops, hit the wrong button. …asserting its capitalist geopolitical imperative has much to answer for with respect to the systemic corruption seen in Guatemala today.