By Fiona B. Adamson for Denver Dialogues

Last week’s news of terrorist attacks in Lahore and Brussels followed only days after similar news from Istanbul. And before that Ankara, Jakarta, and Paris. The list goes on. Attacks on cities around the world are part of the new reality of global insecurity that transcends state and national borders. In addition to the terrible human devastation and fear caused by each incident, they are also examples of how traditional models of “national” security are not sufficient for understanding contemporary patterns of political violence.

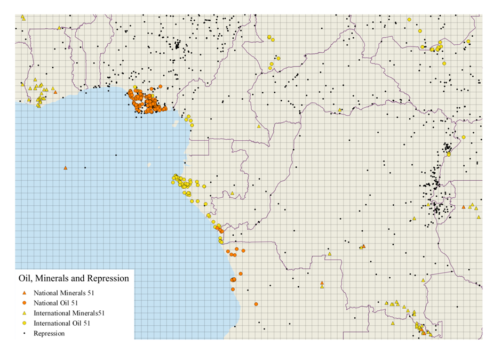

In my recent article for the inaugural issue of the Journal of Global Security Studies (JoGSS) I make a case for moving beyond a “methodological nationalist” bias in security studies. Methodological nationalism is a critique developed by sociologist Andreas Wimmer and anthropologist Nina Glick-Schiller. Although the national state seems to be a “natural” unit, this is partly the result of how the social sciences have treated it. When “security” is assumed to be about how states respond to threats of violence from other states, scholars miss the multiple ways in which political violence is used by non-state actors, but also by states against segments their own populations. For example, in the United States, a national security frame post-9/11 allowed for the militarization of the police across the country in ways that turned military force against unarmed civilians. Similar national security frames allow for deaths of migrants around the world to be ignored as a pressing global security issue—because policy-makers perceive no direct threat to the state. Even many of our datasets on violent conflict such as Correlates of War (COW) rely on this assumption. Uncritical acceptance of methodological nationalism can shape scholars’ normative orientation. Indeed, there are arguably few fields of study in which scholars are as identified with their own state’s interests as in security studies—especially the most vocal of those advocating policy-relevance.

This doesn’t mean that we should throw out the state or refrain from trying to affect policy. But we should pay greater attention to thinking about other spaces in which security might be important. Globalization has in many ways increased the power of states through technological tools like global surveillance and remote control warfare. But globalization also highlights the importance of non-national spaces such as cities, the high seas, cyberspace and various “holding areas” such as refugee camps, detention centers and prisons. In my article I illustrate how the field could benefit from a “spatial turn” by using a “non-national” frame to look at cities, cyberspace, and even the globe itself.

Cities, for example, are important symbols and sites of power in the global economy—many of them contain populations and resources greater than those of some states. They act as nodes that connect transnational networks of capital, culture and politics, as well as functioning as global media hubs. Remarkably, as H. V. Savitch highlights, three out of four incidents labeled as “terrorism” in the past four decades have occurred in cities, with a total of 12,000 incidents altogether. The range of cities that have been targeted—from New York to Abuja, Jakarta to Paris to Istanbul—is an indication that security scholars should be paying attention to cities themselves as entities in world affairs, rather than analyzing such attacks through the lens of “national security.” A national security frame views each incident as an attack against a particular state that only happens to take place within a city. A “spatial turn” instead focuses attention more broadly on cities as new spaces in the changing landscape of global security.

Cities are increasingly significant because new information and communications technology (ICT) allows us to know what is happening around the world in an instant. New ICT however also creates virtual political spaces that transcend national borders—the world of cyberspace. Cyberspace can function as a non-national space where actors fight it out (think here of the hacker group Anonymous issuing threats to everyone from ISIS to Donald Trump). Perhaps more significant, however, is cyberspace’s effect on how we construct narratives of “us” vs. “them.” De-humanizing groups of people is one of the easiest ways to justify violence, and in the past states and other actors could get away with this by tightly controlling public narratives. While actors still employ de-humanizing language to try to justify political violence, this practice is something that can now be challenged and contested on-line through the use of counter-narratives.

We could also be thinking about how increased connectivity means that the most important space for understanding security is actually the globe itself—as a single, integrated space. Violent conflicts in “peripheral” regions of the global economy have consequences in major global cities—what happens in Syria affects what happens in Paris. These connections are missed when we approach the study of political violence as simply about events that happen “over there.” At the same time, suggestions that building walls will keep violence at bay misunderstands how deeply connected we all are now due to globalization—it is not possible to turn back time or technology, and simply reinforcing borders is a retrograde “methodological nationalist” response to complex problems that are essentially global in nature.

How we think about security shapes policy and action. Scholarly analysis might aim to be more self-conscious of this. The rise of global security challenges us to move beyond the methodological nationalist lens that has dominated traditional security studies. A “spatial turn” allows us to see more clearly where security takes place—not just, or even primarily, between states. It directs our attention to the non-national spaces of global security. Cities, cyberspace and our planet itself are just three such spaces; we should look at these and others so as to ensure policy responses that fit the problem.

Fiona B. Adamson is an Associate Professor of International Relations at SOAS, University of London (@FionaAdamson).

2 comments

I am actually surprised that this apparently still seems to be an issue – being a political scientist with a focus on political violence/civil wars, this was the discussion plus 10 years ago (i.a. “human security”, transnational dimensions of civil war, etc.). I mean, are there really still “Scholars [who] miss the multiple ways in which political violence is used by non-state actors” after 9/11?