Guest post by Peter White, Brandon Ives, Paul Huth, and David Backer

Famine is increasingly likely in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, which has been embroiled in armed conflict between the regional government and the Ethiopian and Eritrean governments since November 2020. Alongside reports of widespread killings of civilians, a systematic campaign of sexual violence by Eritrean forces, a growing refugee crisis, and fears of the spread of a broader conflict, recent surveys in the area of the conflict have found “emergency” levels of malnutrition among both children and pregnant women. Another report suggests that there have been approximately 50-100 excess deaths per day since February 2021 in Tigray due to the conflict, with a growing risk that the malnutrition crisis could escalate to outright famine. The Tigray crisis raises the prospect of a recurrence of the devastating famine that swept through Ethiopia from 1983-1985, killing as many as 1 million people—the majority in Tigray.

The tragedy unfolding in Tigray underscores that war is a major driver of hunger. Most food security crises in the world today have important roots in violent conflict. In addition to Tigray, ongoing conflicts in Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and South Sudan, and Yemen threaten mass hunger. Together, these crises have motivated the United Nations and World Food Program to issue a joint “Call for Action to Avert Famine in 2021.”

Famines in the modern era tend to reflect human failures, rather than natural disasters. The issue is not necessarily that sufficient food is lacking, it is that sustenance does not reach those in need. One of these human failures is war. Half of the famines of the 20th century had war as a primary cause. Wars regularly see farmers forced from their fields leaving crops unplanted, unharvested or burnt, and cattle slaughtered. Indeed, militants slaughtered 90 percent of cattle during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide and there are numerous reports in Tigray of Eritrean soldiers burning crops in addition to targeting civilians. The broader population faces empty markets and high food prices as shipments of food aid are interdicted or stolen—indeed, there are allegations of Eritrean and Ethiopian soldiers specifically preventing shipments of food aid and farming supplies from entering Tigray. Armed conflicts also drive civilians from their homes, creating refugee populations that are highly vulnerable to hunger and disease.

Critically, though, while many famines are linked to war, the majority of wars do not lead to mass hunger. In 2017, humanitarian experts and the United Nations Security Council raised the specter of an unprecedented conjunction of simultaneous looming famines in Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia, and Nigeria, explicitly tying the alarm to civil war violence in each setting. Yet long-running conflicts in Libya and Ukraine are not at the same risk of developing into famines. Which wars are likely to lead to hunger crises and which are at a lower risk? Answering these questions is a priority for policymakers, humanitarian organizations, and scholars alike. Political will, public support, and resources for humanitarian action are finite. Understanding which wars are most susceptible to deaths from malnutrition makes for smart and effective anticipatory action.

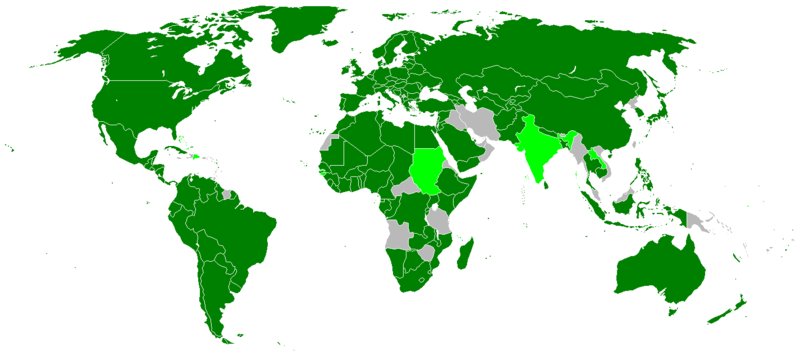

We compiled a new dataset that captures incidence of deaths attributable to hunger during civil wars from the end of the Cold War to 2014. Focusing on violent deaths in wars risks under-estimating the true human impact of conflicts and formulating narrow responses. In our data, we record evidence of any deaths from hunger or related causes during civil war. Critically, our data includes cases of hunger-related mortality that do not meet commonly used thresholds for an official famine declaration. If responses to conflict-related food security crises occur only upon reaching the point of famine, many lives will already have been lost and the wider impact will be felt for years to come. Accordingly, the focus in the humanitarian community is increasingly on “anticipatory action” rather than reactive intervention.

In our analyses, we find clear patterns that provide clues as to which conflicts are susceptible to mass hunger. First, armed conflicts in which insurgents pose a significant threat to the government are more likely to exhibit hunger-related deaths—specifically, rebel movements with large numbers of soldiers and/or which are able to inflict significant casualties on government forces. Under these circumstances, government forces are inclined to use tactics that threaten civilians. These can include attacking the support base of rebels by deliberately targeting civilians and the large-scale use of intensive firepower, such as airstrikes and artillery bombardment, which are likely to result in significant “collateral” civilian casualties. Such tactics destroy crops and foodstuffs, disrupt commerce, and lead to mass displacement of civilians. In Tigray, reports from refugees and the internally displaced indicate widespread direct violence against civilians, including killing and sexual violence, as well as villages destroyed by the largescale use of artillery and tank bombardment in combat and as preparation for Eritrean and Ethiopian military advances. There are also indications in Tigray that direct massacres of civilians often take place in retaliation for a prior attack by Tigrayan forces on Ethiopian or Eritrean forces.

Our analysis reveals that the probability of a civil war exhibiting civilian deaths from hunger increases considerably as either the size of rebel forces or the number of casualties they inflicted on government combatants increases. For example, when the size of rebel forces increases from 1,250 (the average rebel force size in civil wars from 1989-2014) to 250,000 (the approximate size of Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front forces), the expected probability of hunger-related deaths approximately triples.

In addition to Tigray, these findings indicate, for example, that the food security crisis in Yemen could worsen even further as Houthi rebels make gains against the government. Both the Yemeni government and their Saudi-led allies have already engaged in targeting civilians and interdiction of food. On top of this, battlefield setbacks suffered by the government may incentivize further targeting of civilian “soft” targets.

The risks of hunger-related mortality during civil war are hardly limited to extreme cases, such as the conflict in Yemen. Other wars that are not the focus of the same level of significant international scrutiny, deserve action from international governmental organizations and humanitarian actors. Take the conflict in southern Cameroon, where Anglophone separatists achieved battlefield successes in early 2021 with IED [improvised explosive device] and ambush attacks. These rebel successes could lead the government to resort to the type of tactics that not only directly threaten the civilian population, but their food supply as well.

Policymakers and humanitarians should pay close attention to the conduct of wars. The axiom that war and hunger go hand in hand does not always hold true: some civil wars do lead to famine, but the majority of cases do not. The ability to anticipate which cases will fall into each category is important can help to prevent further deterioration into hunger, food security crises, and ultimately famine.

This article is a product of the Modeling Early Risk Indicators to Anticipate Malnutrition (MERIAM) project, which was funded by the UK Aid from the United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). The work of co-authors White, Ives, Huth, and Backer was supported via a subcontract from Action Against Hunger to the University of Maryland. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent official policies of the UK Government or other MERIAM partners.