By Jessica Maves Braithwaite and Emily Hencken Ritter

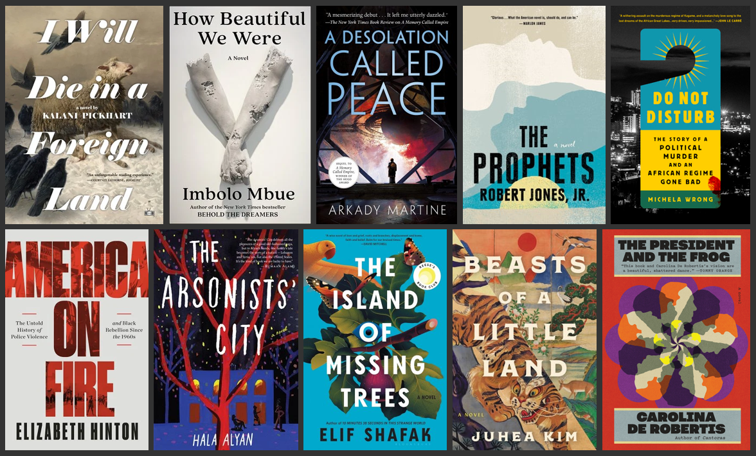

Like we did for 2020 and 2019, here’s a list of our favorite books published in 2021. Despite spending our days researching political violence, we find reading fictional narratives about how individuals experience violence to be deeply impactful. It also inspires new research ideas, and alters perspectives when considering how policies can affect human lives.

If you’re looking for something new in 2022, try one—or ten!—of these great books from last year.

Bonus: Two Must-Read Nonfiction Books from 2021

Jessica Maves Braithwaite is an associate professor of political science at the University of Arizona. Emily Hencken Ritter is an associate professor in the political science department at Vanderbilt University and a permanent contributor at Political Violence At A Glance.

1 comment

The violence in Joe Stafford: A Tale of Revolution is sparing, and mild if you’re thinking of a Hollywood adaptation, but integral to its taut plot.