Guest post by Noel Foster

Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine appears irrational and self-destructive. After all, he had already mobilized over a quarter of his combat forces, stripping his border with China, and expended considerable resources, with no concessions to show for it. He has wrong-footed his advocates in Europe and America pleading for accommodation and arguing he would not invade. He has sent unwilling conscripts into battle. Why?

Putin’s motives might seem a puzzle, had he not been so consistent in expressing them since 2006. In his February 21 televised address, a rambling forty-five-minute speech that—unironically—decried oligarchical corruption and depopulation in Ukraine while proposing a distorted historiography and threatening Kyiv, Putin again articulated Moscow’s position as a revisionist power. Beyond Ukraine, he rejects an international order that undermines Russia’s standing, as he defines it. He demands veto power over the foreign relations of key states in Russia’s near abroad. He seeks the “democratization” of international relations that would give Moscow a greater role in the international system.

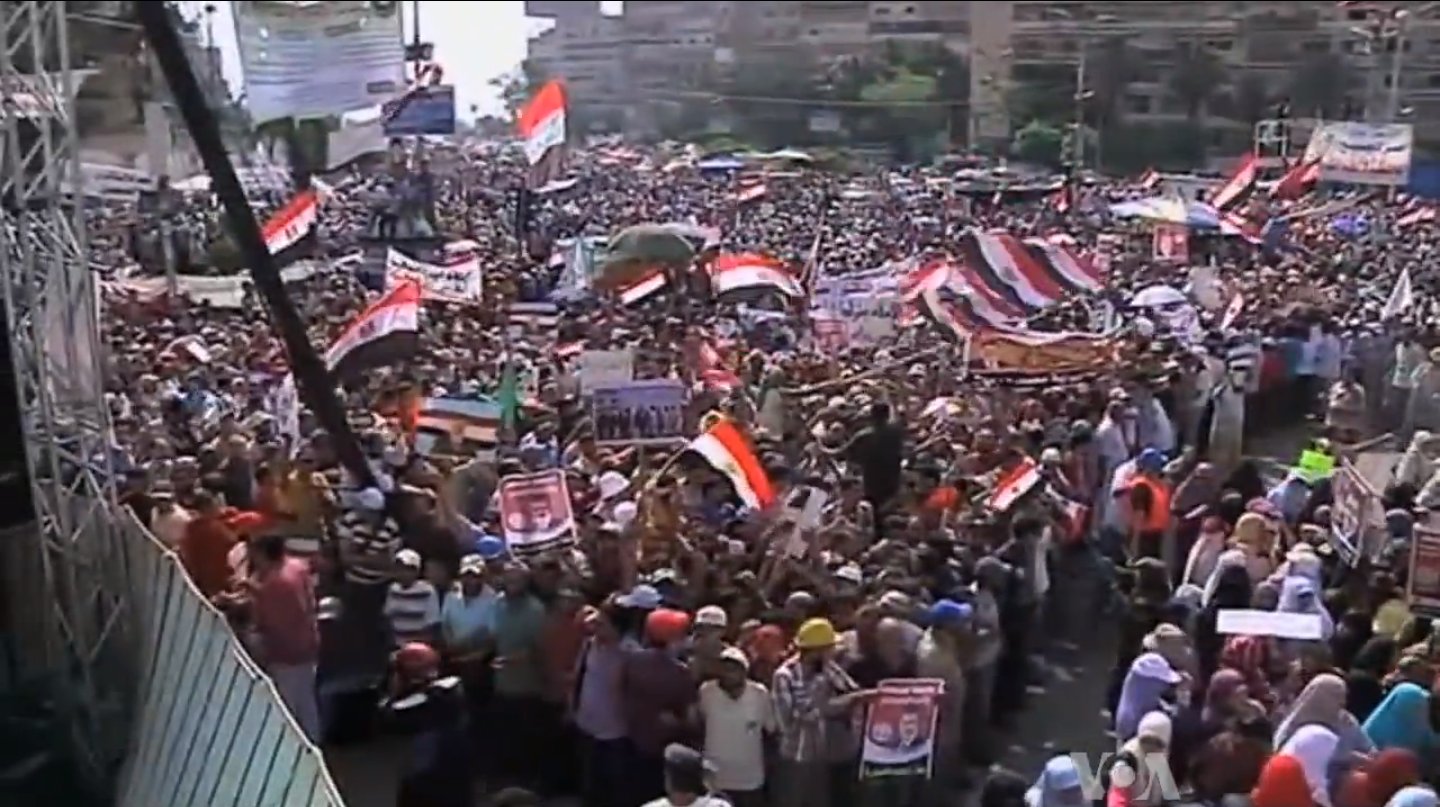

The Kremlin has been accused of waging “hybrid warfare” in its quest for global dominance. But in Moscow’s view, gibridnaya voyna applies to Western techniques employed against Russia. The Color revolutions, not least Ukraine’s 2004 Orange revolution and the 2014 Maidan movement, flow, says Russia, not from complex domestic sources, but from foreign manipulation. In response to perceived Western “hybrid warfare” against Russia, Russian military strategy increasingly incorporates information and influence operations—indeed the ratio of non-military to military operations is 4:1. Russia’s “new-type warfare,” espoused by Russian Chief of Staff General Valery Gerasimov, isn’t new, but rather a continuation of Russian strategic thought dating back to the 1990s and incorporated in military modernization.

The Kremlin pursues its revisionist goals through a strategy of “balancing by off-balancing”—balancing against the hegemonic role of the US in the international order by setting the US and its alliances off balance internally. If Russia’s role in 2016 come to mind for many, its role in the 2016 Brexit referendum, British politics, the 2017 French presidential election, and its place in German media, with its German-language surrogate RT Deutsch taken off the air, also fit within the same pattern.

While much emphasis has been placed on the role of “fake news” and a “firehose of falsehood,” the Kremlin largely employs factual, albeit biased, content in its messaging. The overarching goal is to foster epistemological nihilism in target audiences that makes them distrust their own media and institutions, rendering them more vulnerable to further influence while off-balancing their governments. Steeped in realpolitik and transcending the wartime/peacetime dichotomy, Moscow’s claims are nonetheless moored to normative claims and legal constructs. Moscow claims to have the right to intervene overseas to defend the rights of Russians and Russian speakers—including those without Russian citizenship in the Baltic states. Its claims of a “genocide” against Russian-speakers in Ukraine mimic those claiming a Responsibility to Protect as a way to justify intervention. This is not by accident. Moscow considered the UN-sanctioned 2011 intervention in Libya a betrayal by its Western partners. Indeed, Moscow evacuated civilians in Donetsk and Luhansk to sites deep within Russia on this premise, justifying military action. Armed proxies that maintain frozen conflicts are nothing new on Russia’s periphery, as the survival of largely unrecognized statelets with Russian support—Moldova’s breakaway Transnistria region and Georgia’s separatist governments in Abkhazia and South Ossetia—show. Proxies like the Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR) allow Moscow to destabilize its adversaries and apply pressure strategically at times of its choosing.

Where does this leave Ukraine? At the negotiating table, salami tactics—i.e., divide and conquer—will likely follow, as the Kremlin seeks to divide the Western alliance, with incrementally increasing slices of demands over seemingly minor claims until it receives the full portion of its goals. Washington’s early emphasis on Russia’s troop movements as “the beginning of a Russian invasion” highlight the importance of the semantics involved, knowing that some allies balk at the financial cost of imposing sanctions. Moscow manipulates perceptions and attitudes through exercises and troop movements for “reflexive control.” Belarus’ recent weaponization of refugees renders displaced Ukrainians a priority for the countries’ neighbors.

Where will it end? What Putin’s playbook does not explain is the scale of his risk-taking. After nearly 23 years in power, Putin now faces posterity’s judgment on his legacy, but also a more tenuous hold on power than often acknowledged. A diversionary war to bolster flagging domestic support has been advanced, but this may reverse cause and effect. Putin has imposed painful austerity measures to prepare Russia for war and ensuing sanctions. The unpopular decision to raise the pension age, the accumulation of cash reserves, the attempts to de-dollarize currency reserves and exchanges with partners like China, all indicate that for Putin Russia’s economic policy supports his political objectives, not the opposite.

Putin’s time horizons appear longer and his pain tolerance higher than his opponents. Given that neither Kyiv nor its Western partners made meaningful concessions, Putin decided to employ the “military-technical” measures he had long threatened to compel Kyiv to become a neutral buffer state under his control. Yet having launched a war without a public mandate aimed at the “demilitarization and denazification” [sic] of Ukraine on the onset of his invasion, i.e. regime change, Putin is already proposing direct negotiations with Kyiv, a step he had long refused. Facts on the ground refuse to conform to an autocrat’s will. As the Soviet Union, just like regimes in Portugal and Greece (1974) and Argentina (1983) learned, military setbacks can topple regimes. Having set out denying Ukrainian statehood, Putin has now given Ukrainian fighters a say in his political fortunes.

Noel Foster is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Technology and International Security at the UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation (IGCC). This article reflects the views of the author in a private capacity alone, and do not represent those of any institution.

1 comment

Prime Minister … Mr Putin, sir — sorry to interrupt. Phone call for you. It’s the Hague on line 1.

(NOEL, THX FOR THE CLEAR, CONCISE WORK)