Guest post by Chelsea Estancona and Lucía Tiscornia

This post is part of a series on illicit economies, organized crime, and extra-legal actors and came out of an IGCC-sponsored conference hosted in October 2022 by the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at UC San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy.

On February 13, 2022, millions of bowls of chips and guacamole were making their traditional appearance at Americans’ Super Bowl parties. These avocados had likely been imported weeks earlier from Michoacán, a global exporter of the fruit and the only Mexican municipality licensed to ship avocados to the United States. But on Super Bowl Sunday, these avocado exports from Michoacán temporarily ceased due to a ban issued by the US Department of Agriculture. A member of the US inspection team working in the area had received a threat, resulting in a week-long cut in Americans’ guacamole supply and reduced income for Mexican avocado farmers.

The ban was lifted quickly as US and Mexican authorities vowed continued cooperation to streamline avocado exports. But the incident revealed a dark side of a seemingly innocuous industry: what prompted violent threats against an inspector from avocados’ key export market?

The ubiquity of criminal threats in Mexico is well known, even reaching levels of violence and human rights abuses that surpass those of many civil wars. But such violence is usually associated with drug markets, as labels such as narcoterrorism or narcoguerra suggest. Why would criminal organizations become involved in the market for avocados?

In our research, we show that cartels, much like firms, are forward thinking and economically strategic. Though violent groups primarily focus on illegal markets, they also look for opportunities to expand when licit markets are booming and offer the chance to manipulate a future market. When criminal groups operate in countries that hold a large portion of the export share of a good and these goods become highly profitable due to increases in international demand, this offers criminal groups both an immediate boom in profit and the possibility of exercising future market control. This effect is particularly acute for agricultural goods, which require minimal technology and capital for market entry. In addition, controlling the territory in which these products are grown offers the benefit of streamlining economic activity by engaging in criminal governance.

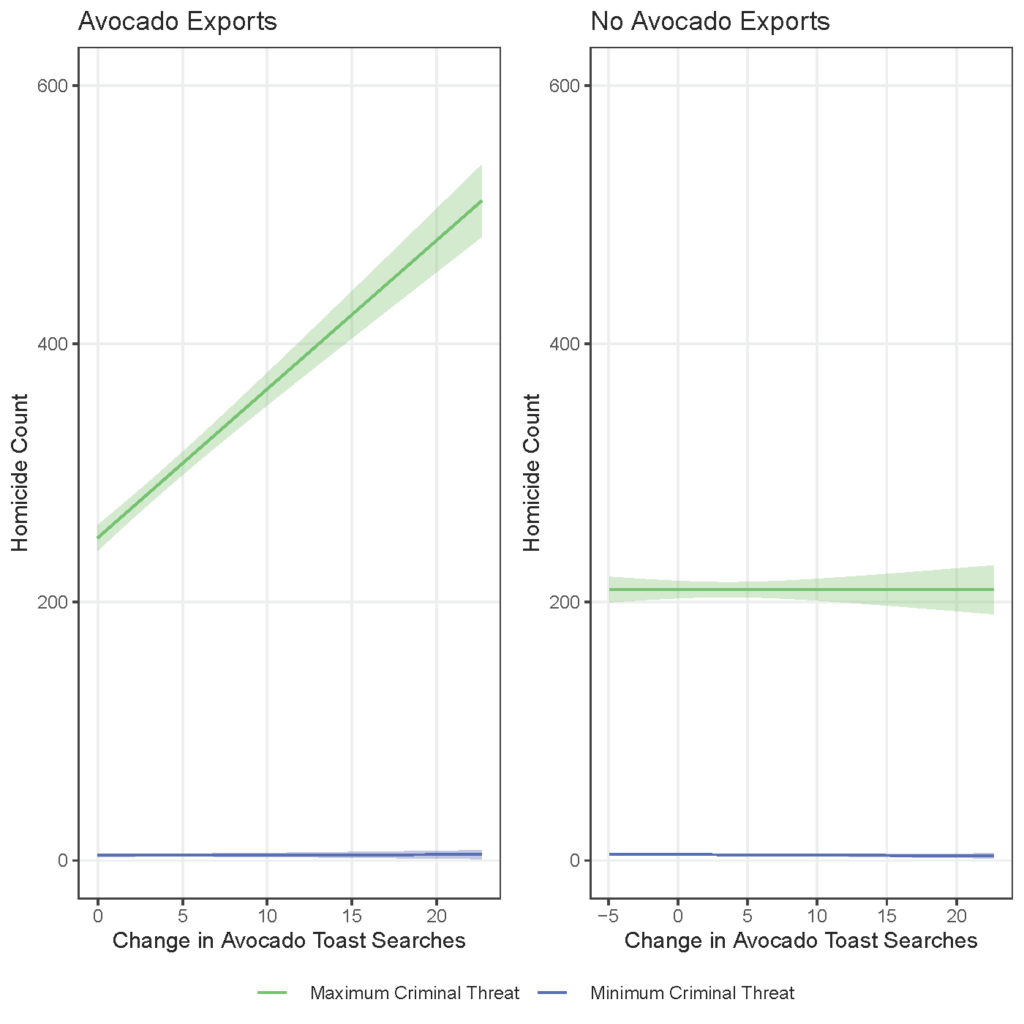

Back to avocados: when avocado demand rapidly increased in the mid-2000s (think avocado toast popularity and “superfood” labels), Mexico was primed to seize a large portion of increasing international avocado profit. Organizations such as the Caballeros Templarios recognized this business opportunity and began extorting and engaging in violence against farmers to control production and shipping. Figure 1 shows an increase in homicides in Mexican municipalities following avocados’ viral popularity—captured in our paper with Google Trends data about searches for “avocado toast.” However, high homicide counts only occur in avocado-exporting municipalities where criminal groups operate. Thus, rapid increases in the export value of agricultural products provide an inroad to licit markets for criminal organizations, prompting localized violence and even high-level threats such as the one against the USDA inspector as these groups vie for market and territorial control.

Mexican avocados are far from unique. Criminal groups all over the world often violently seize opportunities for expansion to other licit markets. Using a sample of over 40,000 observations of cross-national, cross-product, yearly data from 1993–2018, we found that when the value of a country’s export share of an agricultural good rises, it provokes an increase in homicides in countries where criminal organizations are active. For example, the Sicilian mafia violently secured control of lemon exports from Italy when international demand increased in the 19th century. In contemporary South Africa, criminal organizations have sought to violently control the black market for abalone shellfish. Similarly, Colombian and Indonesian criminal organizations have been involved in confrontations with producers over palm oil extraction.

Unfortunately, preventing such violence is a daunting policy challenge. Seizing control of the production of lucrative crops begins locally, and often occurs in areas where the government’s security apparatus is already ineffective or limited. Just as with narcotics, corrupt local officials may also stand to gain from allowing criminal organizations to control certain locally produced goods. Nonetheless, predicting when (following rapid increases in export value share) and where (in areas these goods are grown) such violence, extortion, or other forms of criminal expansion can be expected to occur is a useful tool for allocating limited security resources. In the meantime, consumers beware: your avocado toast or bowl of guacamole may come at a very real, unexpected price.

Chelsea Estancona is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of South Carolina. Lucía Tiscornia is Assistant Professor in the School of Politics and International Relations at University College Dublin.