Should the United Nations Security Council consider a resolution calling for a responsibility to protect the people of the United States from the Trump administration’s handling of COVID-19?

Responsibility to Protect, otherwise known as R2P, is a 2005 UN resolution that declares that when a state either participates in, permits, or is unable to stop large-scale civilian deaths, it has forfeited its sovereignty and the international community has the responsibility to halt the slaughter. Has the Trump administration failed in its fundamental responsibility to protect its population, and should the international community intervene? Nothing of the kind will happen, of course—but that is because of politics, not because a case cannot be made.

A little background: In the 1990s, a series of horrific episodes of ethnic cleansing, war crimes, and genocide led the United Nations to debate what it could and should do in response. As an organization founded on the principles of state sovereignty and non-interference, the UN allows states considerable latitude in terms of how they treat their citizens. But what about events that shock the conscience of humanity? Do states have a license to kill? In response to atrocities, the UN Security Council acted inconsistently: sometimes intervening (as in the case of East Timor), not intervening (as in the case of Rwanda), and prevaricating in others. There were also times when the UN failed to authorize an intervention, but states intervened anyway (as in the case of Kosovo).

By the end of the 1990s, it was clear that the UN needed a rulebook for humanitarian intervention. At the 1999 UN General Assembly gathering, secretary-general Kofi Annan challenged member states to formulate rules for when to authorize the use of force to protect human rights. Ever the global citizen, Canada sponsored an International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, which formulated the concept of R2P, along with a set of principled and pragmatic rules to consider and questions to ask when debating whether or not to intervene.

The philosophical basis for these concepts was that state sovereignty comes, not only with rights, but also with responsibilities, which include protecting citizens from “avoidable catastrophe.” When states are unable or unwilling to do so, then “that responsibility must be borne by the broader international community.” Whether such moments warrant a humanitarian intervention is a matter of debate, but such debates must be had. With some modifications and softening of language, the Commission provided the template for the 2005 UN resolution.

There is on-going debate about what R2P authorizes, whether it is a norm, whether it does more harm than good, and whether it remains relevant. Yet it continues to guide discussions about the responsibilities of states and the international community, and there are three critical elements of that discussion that are germane to the case of the Trump administration’s handling of COVID-19.

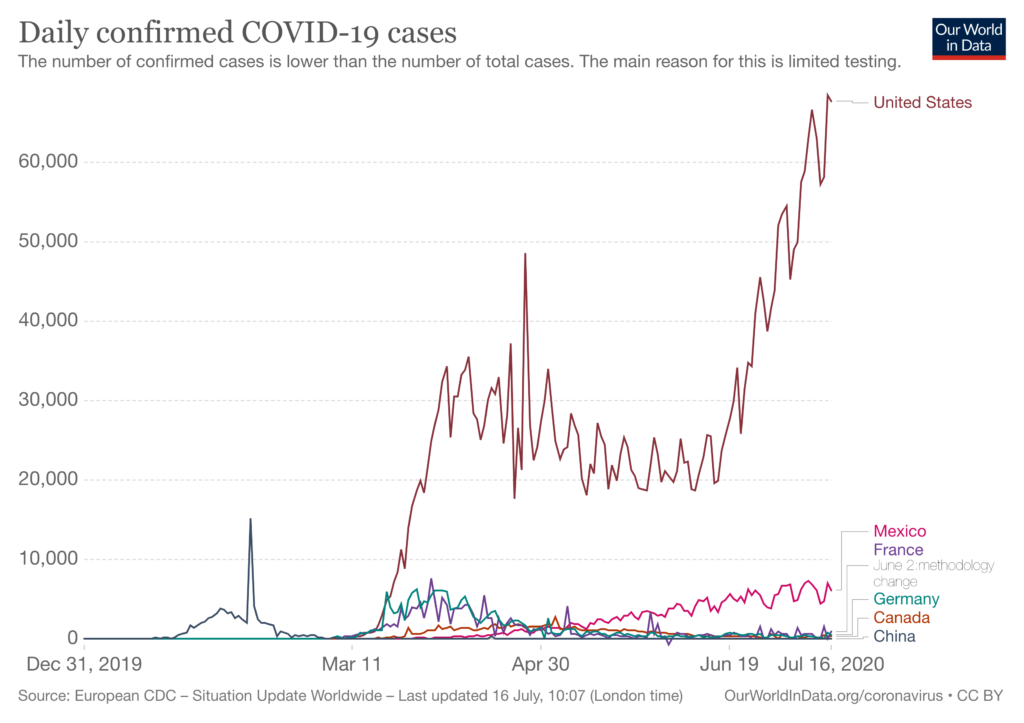

First, is the death toll due to COVID-19 in the US at a level that should concern the international community? R2P did not set a threshold number but instead used the measure of “large-scale loss of life,” to guide intervention. Does more than 130,000 dead in the US qualify as “large-scale,” extreme, and exceptional?

R2P was driven largely by acts of mass killing and pictures of incredible violence. But large-scale loss of life can happen more silently and indirectly. Since 2005, several cases have grabbed the international community’s attention because of the government’s failure to act—or rather its willingness to allow people to die. There were discussions of whether R2P applied to Burma when the military junta refused humanitarian aid following a cyclone, leaving tens of thousands of civilians at risk. A similar conversation occurred when Zimbabwe President Mugabe unleashed economic policies that targeted his enemies and created mass starvation and refugee flight. And, perhaps more proximate to the US case, the relevance of R2P was raised when President Mbeki of South Africa refused to acknowledge the life-saving capacities of antiretrovirals for HIV/AIDS and instituted policies that made them difficult to obtain.

The second question to ask in determining whether R2P might apply to the US is: are people dying in the United States because of the government’s actions and inactions? Many observers believe this is the case. “How many” is a highly controversial, and deeply political, question. But some sources suggest that between 75 percent and 90 percent of deaths in the US could have been avoided by measures employed in other countries. Even a lower figure, say 50 percent, is still about 60,000 lives, and though the numbers keep rising, the Trump administration continues to refuse to take actions that might stem the tide, actions that many other countries have taken and with reasonable results.

Third, does invoking R2P depend on explaining why the government is failing in its responsibilities? Not necessarily. The causes of killing and dying can be difficult to ascertain, both when events are unfolding and after the fact. Usually, though, atrocities owe to some combination of a government’s desire to stay in power, and perceived or manufactured threats from an ostracized minority.

There is considerable mystery regarding the Trump administration’s failure to act. But if previous discussions of R2P are a guide, their inaction likely owes to either political calculations or US security. The most likely explanation is politics. But why? Does it matter that African Americans and Latinos are dying at higher rates than whites? Does President Trump’s sympathy with white nationalism factor into his decision-making?

The Trump administration has failed in its responsibility to protect Americans—that is clear. What will—and what should—the international community do in response? The use of force is out of the question. R2P has evolved over the years, and is no longer tied to military instruments. COVID-19 is a medical emergency, and the international community could provide more medical assistance to neglected or abandoned communities, much as Medicines Sans Frontiers is doing for Native American communities. Other American communities that lack testing kits could request assistance from countries such as South Korea and Taiwan that have demonstrated considerable acumen. There is a good chance the United States government would refuse the assistance, much like Myanmar and South Africa did. But it is worth a try.

Should members of the Trump administration be charged with war crimes? In previous discussions of R2P, those who have failed in their responsibilities have been considered candidates for international criminal justice. That won’t happen, but when government officials fail in their responsibilities—and these failures are not accidental but a matter of policy—then questions of accountability and justice must be asked. How should officials whose policies have led to thousands of deaths be held accountable? What happens when we no longer think of Trump’s policies as merely reckless, but instead as crimes?

There will be no debate about R2P and the United States’ handling of COVID-19 at the United Nations Security Council. But its possible applicability shows the severity and gravity of the situation in the United States, reorients how we situate the rising death toll, and raises deeply troubling questions about how we frame the US government’s failure to protect.